Abstract

Questions abound over how universities should teach and prepare the next generation of researchers to confront current and future wicked problems. With so much focus on curriculum and training, it is crucial that we step back and reflect on higher education’s capabilities to foster solution-oriented, collaborative research. What do the institutional incentive structures in higher education support, in terms of practices and outputs related to scholarship? And are those structures felt evenly across the academy? Those doing research in these spaces—in terms of title, autonomy, power, privilege, and status—vary widely by their institutional locations as well as in terms of their ties to broader disciplinary norms. To assess whether these dynamic, contested institutional landscapes afford so-called wicked problem scholarship, this paper draws from survey and interview data collected from 44 researchers working at the nexus of food, energy, and water systems at Carnegie Research 1 universities in the United States. Findings point to an uneven institutional landscape, which is shown to shape in different ways the type of solutions-oriented, collaborative scholarship fostered across the five positions examined. The paper concludes by reflecting on the paper’s findings, particularly in terms of what the data tell us about higher education as a place that fosters wicked problems scholarship, while also highlighting the study’s limitations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of “wicked problems” was first introduced in 1973 by Rittel and Webber (1973). In the last two decades, however, this neologism has gone from relative obscurity to a topic of systematic literature (e.g., Lönngren and Van Poeck, 2021) and bibliometric (Hou et al., 2022) reviews. Wicked problems speak to issues without objectively right or wrong solutions as “answers” rest on competing visions of what ought to be (Bowman et al., 2022; Jasanoff and Simmet, 2017).

Calls are being made to train wicked problem scientists and scholars (e.g., Kawa et al., 2021; Krause, 2012; McCune et al., 2021). (Not all innovators in the academy identify as a “scientist,” such as those in the humanities and creative artists, which explains my preference for the more inclusive term “scholar.”) The intent of these appeals is to better equip society to tackle today’s seemingly intractable and in some cases existential, controversies (Carolan, 2022). Yet this prioritization of training sidesteps questions about the extent to which higher education is structurally and culturally capable of supporting solutions-oriented, collaborative research. It is important to highlight, too, that those doing research in higher education hold diverse titles, due to inhabiting different social locations within these institutions. What does “solutions-oriented, collaborative research” look like in higher education across those locations, in terms of their respective practices and outputs? This is a key question answered in this paper.

We also know that science and scholarship are neither practiced nor valued in monolithic ways, which is to say, “standards of ‘good science’ [--or ‘good research’, ‘good scholarship,’ etc.--] vary across research communities” (Koch and Tetley, 2023, p. 2). This results in the valuation of research and scholarly outputs being hotly contested, across and within disciplines (Koch and Tetley, 2023; Falkenberg, 2021). These diverse communities of practice come together under one institutional “roof” in higher education; sites that support much of the world’s research (NSF, n.d.). One factor repeatedly called out for having an undue influence on the academy, which is generally characterized by marketisation, stratification, and a heavy reliance on performance metrics, is known as the neoliberalization of higher education (e.g., Bowman et al., 2022; Berg et al., 2016; Busch, 2017). The data presented speak to these concerns, trends, and tensions from the standpoint of those practicing wicked-problems scholarship while suggesting ways for higher education to be even more supportive of solutions-oriented, collaborative research.

The next section sets the stage, elaborating on the point that neither research nor higher education are islands onto themselves but are nested within social networks, resource flows, and power differentials. Attention then turns to a review of the methods used to collect the data. The data examined come from survey and interview data collected from forty-four researchers at Carnegie Research 1 (R1) universities in the United States (US). R1 universities have “very high research activity” (e.g., Nietzel, 2021)—the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Higher Education has classified 146 US institutions as having R1 status. In addition to being rooted in different disciplinary orientations, respondents held different positions within their respective institutions.

The Findings section identifies specific “challenges” and “rewards” identified by respondents and explains why they were prioritized differently across those different positions. The themes highlighted in this section add nuance to concepts outlined prior, such as around the contested nature of “good research” and the neoliberal university. The “Discussion” section leverages those themes and data to make recommendations aimed at fostering solutions-oriented, collaborative scholarship within the academy.

Situating scholarship

I begin clarifying my use of certain terms. While distinctions have regularly been made between the terms inter-, multi-, and trans-disciplinary research (e.g., Fawcett, 2013), bibliometric analyses indicate “interdisciplinarity” remains the most used; often, too, as a catch-all that includes those other subtypes of collaborative research (Leydesdorff and Ivanova, 2021). I follow this practice, using “interdisciplinary” in this inclusive way. Another key term in this paper is wicked-problems scholarship, which refers to research that “tackles grand challenges that affect diverse groups of stakeholders who disagree about the nature of the problem and its causes” (Kawa et al., 2021, p. 2). Wicked-problems scholars must have disciplinary expertise coupled with a “purpose-driven commitment to problems that defy easy resolution and require stakeholders to work across ideological and epistemological differences” (Kawa et al., 2021, p. 2).

Research, whether single-disciplined or interdisciplinary, occurs within and is thus structured by symbolic and material fields (Bourdieu, 2004) inhabited by different stakeholder groups: funders, university administrators, donors, policymakers and politicians, researchers, and, in instances of community-based research, community partners (Albert et al., 2017). Research questions, too, are products of a broader socio-political milieu. These are shaped by such phenomena as scholars’ interests and values, funding environments, geopolitical and ecological realities, and disciplinary and institutional norms (Busch, 2017). Research-related resources—material as well as symbolic—are allocated unevenly based on often-implicit values. We see this demonstrated through, say, the tacit ranking of disciplines, with priority generally given to those that either generate commodifiable outputs (intellectual property, material “widgets,” etc.) or that promise to enhance and thus further entrench market logics (i.e., economics) (Guler and Tuzunoglu, 2019).

Disciplinary training is also disciplining, making the term “academic tribe” an apt descriptor (Becher and Trowler, 2001), though even within disciplines considerable variations exist relating to what “good research” looks like (Koch and Tetley, 2023). Drawing on interview data from women academics in Finland, a recent study “traces subtle obstacles, hidden power relations and invisible hierarchies in interdisciplinary research work” (Ylijoki, 2022, p. 356). One strong disciplining norm to came out of the interviews was the prioritizing of discipline-based peer-reviewed outputs (Ylijoki, 2022). This norm disincentivizes solutions-based, collaborative research in a couple of significant ways. First, it does this by making collaboration on outputs difficult, as discipline-based publications require local, discipline-specific knowledge that people from other “tribes” generally lack (Turner et al., 2015). And second, we know that wicked problems scholars are more likely to be unsatisfied with the prospect of only engaging in knowledge production for knowledge production’s sake, which is to say, these individuals want to not only study the world but to change it (e.g., Carolan et al., 2023; McGreevy et al., 2022).

This pressure to publish, especially in the context of higher education, is reflected in the findings of a study examining the volume of articles indexed in Scopus and Web of Science (Hanson et al., 2023). To quote the study’s authors:

“Total articles indexed in Scopus and Web of Science have grown exponentially in recent years; in 2022 the article total was 47% higher than in 2016, which has outpaced the limited growth—if any—in the number of practicing scientists” (Hanson et al., 2023, p. 1).

The study provides strong evidence that the speed of the publication treadmill is quickening whilst reinforcing valuations that equate “research excellence” with metrics having to do with things like “citation rate” and “Impact Factor” (Hanson et al., 2023).

The above evidence relating to the peer-reviewed publishing industry, and the links implied between the study’s findings and profit motives driving those trends (Goodkind et al., 2023), is a sobering reminder that research, science, and higher education are also industries. To further explore this point, I turn briefly to the subject of the neoliberal university (Ball, 2012; Canaan and Shumar, 2008). I am using the term “neoliberalism” to refer to discourses, ideologies, and practices that have varied over time and space while also sharing enough of a family resemblance to be recognized within the same term. This family resemblance centers on the following issues, which are generally expressed (or at least strongly implied) in any definition of neoliberalism: prioritization of markets over overt government regulation, which also implies a preference for the privatization of social goods; favoring trade liberalization over protectionism, which, again, includes liberalizing “public” goods (think education, knowledge, etc.) as opposed to shielding (protecting) them from market forces; and an approach to valuation that prioritizes efficiencies, economic returns on investment, and metric-based forms of evaluation, which, again, privileges economic reductionism (Harvey, 2005). The rise of deregulation and the rolling back of the state in the 1980s in the US (Reaganomics) and the United Kingdom (Thatcherism) involved a variant of neoliberalism that emphasized market expansion and entrepreneurialism as answers to social responsibility (Friedman, 1970).

In this environment, universities have begun to see their “public” (taxpayer) support drop, resulting in a deficit that, in turn, needed to be filled with rising tuition rates/revenue. Facing this economic precarity, university administrators are therefore attracted to neoliberal principles and practices—efficiency, prioritizing investments by their return on investment (ROI), etc. One of the responses taken by universities in the face of this economic precarity is to create conditions that mimic that precarity among their rank-and-file, including among those who are part of higher education’s research enterprise. For example, the non-profit advocacy group, the New Faculty Majority (2021), estimates more than 75% of university professors are now employed on at-will contracts, with half (roughly 700,000 individuals) working as “adjuncts”—a contract status especially easy to terminate. This is a stark change in employment status for this group, recognizing that some 78% of faculty were “tenured” or “tenure-track” in the 1970s (Shermer, 2021). What does this shift in employment status, from tenure-based to at-will contracts, mean in terms of the type of research these individuals practice and the artifact that result from these activities? This is one of the empirical questions examined in this study.

Universities are also working to systematize relationships at the public-private interface to diversify revenue streams in the face of dwindling public support, examples include investments directed at building technology transfer offices and robust extramural funding-directed research infrastructure (Stankevičienė et al., 2017). Yet prioritizing departments and disciplines that have a greater capacity to fundraise undermines those units with historically strong ties to the welfare state (e.g., social work, public health, the social sciences) while strengthening the position of those more closely aligned with industry (Moore et al., 2011). These trends in higher education suggest we are seeing a “general spread of the ‘culture of commerce’ to academia” (Moore et al., 2011, p. 524). Solutions-oriented, collaborative-based scholarship, in contrast, is heavily interested in producing outputs that are seen as public goods, to help all versus only those who can afford it (El-Zein and Hedemann, 2016; Scholz, 2020).

Neoliberalism also encourages a heavy reliance on performance metrics (e.g., Bowman et al., 2022). This move is legitimized based on, for instance, discourses of fairness, as everyone is said to be evaluated against the same ruler (e.g., grant dollars brought in, student credit hour production, number of publications, annual citation rates, h-index). Yet equality and equity are not the same thing, which is to say, sometimes the fairest thing to do is to treat scholarship differently based on an understanding of their respective socio-historical standpoints (Cook and Hegtvedt, 1983). This privileging of certain (read: neoliberal) performance metrics thus helps explain struggles faced by the humanities and to a lesser extent the social sciences. As audiences (taxpayers, politicians, university administrators, parents, students, etc.) are conditioned to narrowly defined value propositions, usually having something to do with money (Di Leo, 2020), certain pockets of the university that speak a different language of “value” struggle to have their worth realized.

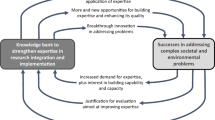

And yet, there is a growing societal need for wicked problems scholars. I do not want to suggest that universities have resisted entirely the push to reimage what it means to do “good” research, as evidenced by the fact that terms like “interdisciplinary,” “collaborative-research,” and “wicked problems” are regularly evoked in research calls for proposals and strategic planning documents throughout higher education (e.g., Evis, 2022). Publishing data to some degree also supports the observation that change is afoot, as there has been a marked rise in co-authored publications in recent decades (Bandola-Gill et al., 2022).

I am not aware, however, of a study that looks across the various scholarship-based standpoints that exist at universities for the purpose of mapping out the incentive structures, norms and lived experiences that shape how, why, and for what purposes research gets done. This paper attempts to do that. The following section introduces the methods used to collect the data that will help fill in some of those gaps in the literature.

Methods

The following positions were identified, and participants were recruited from each category: graduate student/postdoc (GS/PD); grant-funded research scientist (RS); untenured tenure-track faculty (TTF); tenured faculty (TF); and university extension scientist (ES). The GS/PD category included both doctoral candidates and postdoctoral researchers (a doctoral candidate has completed their coursework in a doctoral program and is focused on their dissertation). The RS category refers to those with a title like Research Scientist—a grant-funded position with a research focus. TTFs are better known (in the US) as Assistant Professors, whereas TFs refer to Associate and Full Professors. ES are found at Land Grant Universities and are often field-based researchers with a doctorate. (A Land Grant University is an institution of higher education in the US designated to receive resources through, for instance, the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890, while more recent legislation in 1994 established Land Grant Tribal Colleges. The aims of these institutions are many, though all have a mission that emphasizes serving the public good [Gavazzi and Gee, 2018].) Unlike their campus-based colleagues, however, who usually have appointments that consist of some mix of teaching and research, extension scientists are generally evaluated on engagement-based metrics. Their role, in other words, is incentivized to focus on things like technical assistance, practitioner (e.g., farmer/rancher) support, and business/entrepreneurial incubation, resulting in a more applied type of research.

Recruitment

This study was vetted and ultimately approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Colorado State University (ethics approval number 2279). Respondents were promised anonymity and protocols were established to ensure this vow. I reached out to colleagues across the US known to be collaborative scholars, making sure requests to participate were sent to individuals across all five positions. To narrow the sample universe, I focused specifically on those conducting research at the so-called nexus of food–energy–water systems (FEWs)—a highly interdisciplinary area of research that has seen rapid growth in the US in the last decade (e.g., D’Odorico et al., 2018; Proctor et al., 2021; Wade et al., 2020). To quote from a recent review article on the topic, “the term Food–Energy–Water nexus […] refers to the idea that food security, energy security, and water security are inextricably interdependent” (Proctor et al., 2021, p. 2). FEWs is an area I personally conduct research in. My hope was that this strategy would increase the study’s response rate, by leveraging whatever reputational capital I or my institution might have in this space.

Care was taken to recruit GS/PD and RS, as my networks consist heavily of those from the TTF, TT, and ES categories. Those contacted were therefore asked to provide names and contact information of collaboratively minded individuals, working at the FEWs nexus, from these categories. I avoided interviewing anyone I had collaborated with in the past to avoid perceived conflicts of interest. Everyone was initially asked the following screening questions:

“Do you consider yourself committed to collaborative research, defined by ‘a sustained engagement between researchers (professional scientists or scholars), practitioners (e.g., farmers, natural resource managers, policy makers), and community stakeholders (e.g., those impacted by activities/decisions of practitioners)’?”

Sample population

Table 1 details demographic information about respondents. Categories under “discipline area” reflect the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) seven “directorates” (NSF, n.d.). An eighth category was added to better represent the breadth of disciplinary expertise in the sample. This category was labeled “humanities and visual/performing arts,” which consisted of three philosophers, one historian, and one rhetorician. While these categories might seem ambiguous to the uninitiated, those interviewed seemed familiar with them and were quick to locate themselves within one.

Research and coding approaches: an iterative two-phase process

Qualitative data collection occurred over two phases. During phase one, from May 2021 through September 2021, 44 virtual face-to-face interviews were conducted. Interviews ceased when conceptual themes and connections started to “solidify”—a process known in qualitative methodology as theoretical saturation (Guest et al., 2020).

Interviews lasted approximately ninety minutes and were recorded and transcribed. The questions asked interrogated the following themes: interdisciplinarity/wicked problems; opportunities; goals; barriers/challenges; performance measures; values; risks; stakeholder engagement; and higher education and disciplinarity. Questions were tested beforehand with individuals who the author has collaborated with, to ensure legibility.

Interview data were organized and coded with assistance from NVivo 11 software (2015). First, I became familiar with the data through active reading while making notes of patterns. This allowed me to generate initial codes based on connections between different aspects of the data, a process known in some circles as “open coding” (Saldaña, 2013). Codes were then continually refined (e.g., bundled/collapsed), which is known as “focused coding” (Saldaña, 2013). With focused coding, themes, concepts, and relationships are curated and re/organized into meta-themes; a process that allowed me to identify the top eight challenges and the top eight outputs/rewards for each respondent.

The second phase of data collection occurred from December 2021 to March 2022. Those eight challenges and outputs/rewards were listed on a Qualtrics survey, with quotes to illustrate meanings attached to each. Respondents were then asked to rank each from least to most important, drawing from their personal experience to inform the exercise. All 44 respondents completed this survey. Within one week of completing the survey, respondents were contacted for a brief (15–20 min) virtual interview where we talked through their rankings, which gave respondents a chance to contextualize their answers. These follow-up interviews were also recorded and transcribed.

Findings

Table 2 presents the eight most prevalent challenges and outputs/rewards identified from the qualitative data. To better illustrate the meanings and values associated with each challenge and output/reward, two representative quotes are included. To recall, those challenges and outputs/rewards were eventually ranked by all respondents. The remainder of this section investigates those rankings across the various job titles.

Top eight challenges

Figure 1 lists “challenges” (in no order) identified in Table 2 with data from the Qualtrics survey, noting ranges and means across position types from the ranking exercise. Time was viewed very differently across positions. For TF, ES, and RS, time was deemed a less significant challenge relative to other positions identified. Alternatively, all GS/PD and TTF cited this challenge as a major, if not the most significant, barrier to collaborative research. (Note: these institutional locations are supported by contracts with finite time horizons.) This challenge for GS/PD and TTF spills over into, and thus further explains, other challenges reported by respondents in these positions, as I reveal shortly.

Power dynamics were identified as either a moderate or significant challenge by all respondents. University extension scientists, on average, viewed this theme as more significant than any other group, in large part because of their unique roles that involved them having “one foot on campus and the other in the field” (ES #4); a social location “that makes you especially concerned about doing research that doesn’t run roughshod over the communities you’re trying to serve” (ES #9). Other groups noted this concern as they highlighted their own marginalized position within the university (e.g., GS/PD, TTF). To quote two from the GS/PD category:

“Post doctorates are in this weird liminal space. Where we’re not faculty, even though we have a PhD, and we don’t have much if any representation as a group.” (GS/PD #2)

“Graduate students are ‘students’ but also not. When the university thinks of ‘students’ they think undergrad [student]. […] So, their [i.e., graduate students’] research efforts can be exploited. I think we’ve all seen that happen.” (GS/PD #8)

Funding mattered immensely to all respondents, as noted by the significance attached to funding structures, though it also clearly mattered more for some groups. Those holding institutionally secure positions—recognizing there is nothing more secure (allegedly) than having tenure at a university—tended to express less concern over funding. Alternatively, those whose jobs depended 100 percent on obtaining external (e.g., grant) funding felt constrained by the type of collaborative research that they could practice. To quote one RS:

“I hate to say this, but I can only ask research questions that come with significant enough funding to cover my salary. And forget about raising politically controversial questions. Not only do those not get funded but you risk branding yourself as a ‘rabblerouser’ who allegedly cannot be trusted to do objective science.” (RS #3)

Communication to broader audiences was another challenge ranked very differently depending on where respondents institutionally “stood” within their university. To be clear, all participants talked about the personal importance they placed on speaking outside their discipline, if not beyond the university. Yet none were confident that either their institution or discipline felt the same about this skill and practice. To quote one GS/PD:

“I think we ought to be able to communicate our findings to a general audience. But if I only did that, I’d never get a job [at a university]. On the flipside, because it [academic marketability] is all about peer-reviewed publications, my chances of landing a job at a top research university are increased if I focus exclusively on talking to those in my discipline, while ignoring speaking to those broader audiences.” (GS/PD #4)

All respondents reported building trust to conduct research as important. Their perceptions differed, however, from the standpoint of identifying how challenging it was to build this trust considering their institutional location within the university. Trust building takes time; a reality made even more challenging by the asymmetrical relationships between trust building and trust erosion—think of how one act of infidelity in a relationship can permanently destroy decades of otherwise trust-affirming behavior (Sztompka, 1999). Those with tenure, for instance, were more likely to indicate having the luxury of time to engage in these trust-building activities, especially compared to, say, TTF—e.g., “The tenure-clock is ticking to acquire publications and grant dollars, not social networks” (TTF #3).

A slightly different temporality was expressed by ES, which influenced this group’s perspective of trust-building with stakeholders. A representative quote expressing this point goes as follows:

“I’m all for taking time to build trust. But the communities I work with also want results, with many individuals wanting those results yesterday. […] Finding a balance between those two poles can be really challenging in my role.” (ES #6)

This individual later explained how community stakeholders do not have endless resources, which include the resource of time. “If they trust you, they’ll likely work with you,” she told me, adding that “you still need to co-produce something useful in relatively short order; otherwise, folks risk viewing that collaboration as time wasted” (ES #6).

Maintaining partnerships beyond the project was not considered a significant challenge for GS/PD because of their temporary positions at their university. This made long-term relationship building with local stakeholders less of a priority for them, even though all talked about eventually wanting to do that “once a longer-term position is secured” (GS/PD #9). TTF also rated this item as less of a challenge because their priorities were elsewhere, namely, in securing tenure. This resulted in them pursuing activities (e.g., writing articles for peer-review) more likely to achieve that end. As one respondent explained, when asked why community partnerships are not something typically valued in this process—“Nowhere on my CV does it talk about ‘community relationship building,’ though, believe me, I wish that was a disciplinary norm” (TTF #2).

We therefore see in these examples positions within higher education where long-term partnership maintenance might be important for respondents. Yet, because the activity is so far outside the bounds of what their positions allow, the activity did not even register as a “challenge.” In contrast, ES also ranked this challenge (i.e., maintaining partnerships…) low on their challenge list but for very different reasons, namely, because their institutional location incentivized and rewarded this activity.

Related to long-term partnership building, recognizing that before one can grow a relationship the seed must first be planted, is the next challenge: finding collaborators. Not surprisingly, this challenge was less challenging to ES because the position values and institutionally supports the activity. TF were also less likely to see this as challenging, mostly because they had already taken the time to build many of those relationships. For others, however, finding collaborators proved a significant challenge, in no small part because of how insular universities (and disciplines) can be from the communities and states within which these institutions are embedded. This can be especially challenging for those in departments, schools, or colleges who lack a strong history of collaboration and the social networks (e.g., social capital) those activities build. To quote one respondent:

“My department doesn’t have the same connections to Extension or to community partners like other units [departments], so I find it especially hard making connections with groups outside the university.” (TTF #7)

Reports of having effort fairly counted as an obstacle also varied considerably depending on one’s role within the university. All TTF rated this as a significant challenge. GS/PD also reported this to be a significant challenge, though their mean “score” is lower compared to TTF. Part of this discrepancy between the two positions has to do with the fact that TTF has committed to life within the academy and all the norms, values, and expectations that come with this position, including the fetish over peer-review publications (Derricourt, 2012). GS/PDs, alternatively, are still weighing their professional options of whether to pursue a career in higher education, the private sector, government, or NGOs. For those in the GS/PD category, then, the norms of what “counts” in higher education might have less of an impact on their ultimate career aspirations, especially for those interested in positions outside the academy.

Top eight outputs/rewards

The outputs and rewards discussed mirror many of the challenges just described. Figure 2 lists the top eight outputs/rewards, with ranges and means.

Peer-reviewed publications were viewed as the gold standard output for some categories of respondents (e.g., TTF), while others explained that this output held far less significance (e.g., ES). Take the following quote from an ES: “Publishing a peer-review article is nice but it doesn’t create jobs” (ES#1)—an example of just how different their expected (applied) research outputs are relative to their on-campus peers. When asked to explain why they chose to foreground job creation when assessing outputs and rewards, their response pointed back to their position’s institutional location and the incentives attached. In their words, “I don’t get evaluated by number of articles published but by things like business incubation and job creation” (ES #1). She also mentioned how, “unlike professors [on campus], who report directly to others on campus, I am just as responsible to people in the field.” When asked to give an example of who these “people” might be, among those mentioned included “county commissioners, politicians, and business leaders—basically, individuals powerful enough to get me fired if it don’t focus on the right thing” (ES #1). I want to also call out the variability of responses to this output/reward among TT, with some valuing peer-reviewed publications as “most important” while others valuing these outputs far less.

Digging further into the ranking data reveals Full Professors, on average, placed less significance on this output/reward than Associate Professors—a mean of 7 and 5, respectively. This suggests that some of the disciplining signals expressed and felt among TTF are also experienced by Associate Professors, as evidenced by this need to follow the “rules of the game” (Bourdieu, 2004) to secure promotion to “Full.” When taken together, these findings point to how research output valuation is contested and rooted in one’s institutional locations within and beyond the university, where what “counts”—or what is “right”—is dictated less by objective measures and more by the norms of one’s community of practice.

The institutional location also impacted the importance attached to social networks outliving projects. This output/reward was highly important for ES, in large part because this, too, was captured in criteria their supervisors used during annual evaluations. As one explained, “I’m asked [in my annual evaluation] to detail how I’ve increased the capacity of my community and that includes its social capacity […] which can be captured in metrics having to do with the number of community and outreach events and participation numbers” (ES #7, emphasis in original). Alternatively, this output/reward was relatively unimportant for GS/PD, which, again, had a lot to do with the short-lived nature of the positions—e.g., “Creating enduring networks is never a bad thing, but I’ll never reap those benefits because I’ll be gone in less than two years” (GS/PD #6).

All respondents reported helping facilitate social change as having at least moderate importance. While the response range for TF was “wider” than for other groups, their mean does not reflect a deviation. The consensus across all positions was that it is not enough to just study the world. All respondents, to various degrees, wanted to play a role in helping change it. Curiously, while a priority for all, the data indicate that only one group was explicitly evaluated according to whether they helped implement social change, i.e., those from the ES category. Regarding the other groups, some expressed concern that researchers in higher education are hindered in their ability to facilitate social change because there is the expectation that researchers cannot “take sides,” to quote one RS (#2). When asked to elaborate, they added:

“Avoiding the taking of sides creates a strong disincentive to be a part of social change, because when you change the world you almost ways create winners and losers. That can get us in trouble because scientists are supposed to be objective, which means explicitly not taking sides.” (RS #2, emphasis in original)

Changing disciplinary/academy practices

All respondents thought this ought to be a long-term goal of collaborative scholarship. Yet, TTF did not rank this output/reward highly when completing the ranking survey, as they believed their institutional location made them powerless to implement this type of change. The following is a representative quote capturing this sentiment:

“I’d be swimming against more than a century of scholarship and values and beliefs and expectations if I thought little-old-me could change what my discipline values and believes. I think I can better effect change elsewhere, versus wasting my time trying to change what I can’t.” (TTF #5)

In contrast, TF and RS ranked this out/reward quite high, especially relative to TTF. TF—through their seniority and thanks to having legitimacy among peers—felt empowered to “shaking things up,” as one respondent put it (TF #10). ES, meanwhile, felt their liminality—as having “one foot on campus and another in the field” (ES #1)—meant they could take risks and experiment in terms of how they practice “scholarship” in ways that many of their peers on campus could not.

Recognition by disciplinary peers had among the most diverse rankings across positions, with means ranging from (approximately) 1 (i.e., ES) to (approximately) 7 (i.e., GS/PD). Given that these outcomes/rewards were tethered to discussions about interdisciplinarity, these responses suggest that meanings of “interdisciplinarity” are shaped by individuals’ social locations in a research university. To put matters plainly, certain locations make it easier to foreground the “inter” of interdisciplinarity, while for others, interdisciplinarity is understood as disciplinarity-by-other-means—i.e., where the outputs, rewards, and incentives remain strongly tethered to disciplinary norms. One TTF member gave the following answer when asked to explain their desire to be recognized among disciplinary peers, even though they referred to themselves as a “interdisciplinary researcher through-and-through.” In their words,

“When it’s time for me to go up for tenure and promotion, it will be disciplinary peers from other universities evaluating me. I don’t like that fact, as I want to speak to a broader audience with my scholarship. But my hand is forced. I feel like I must think a specific way and practice a certain type of “research” [making air quotes with fingers] to get tenure.” (TTF #4, emphasis in original)

Non-academic communication channels

This output/reward was considerably less important to those facing the tenure-clock (i.e., TTF), as it was believed non-academic outputs “counted” less (if at all) for tenure and promotion and in annual evaluations for this group. The mean for TF on this output/reward was 3, signifying they placed slightly less significance on this output/reward than their untenured colleagues. While TF do not face the same pressures to publish, having already secured tenure, they still inhabit the same community of practice, which is to say, they are still “disciplined” by their discipline. And as noted in a prior section, the signals to publish in the academy remain just as strong, if not stronger, today than ever before (Hanson et al., 2023).

Opportunities for others to have these experiences and discipline porosity

I want to discuss the two remaining outputs/rewards together, as I see them as representing different sides of the same coin. Those who valued opportunities for others to have these experiences spoke of wanting to push the boundaries of what it means to do research, which involved seriously rethinking who was involved (and excluded) in that process. Discipline porosity, in turn, speaks to institutionalizing these more inclusive understandings of “research,” “science,” and “disciplinarity.” To put it another way: the former speaks to changing what happens in the field, as we practice collaborative research, whereas the latter speaks to changes that need to happen on campus (and throughout the academy), as we evaluate and reward collaboration and train students to be proficient in these practices.

ES placed greater importance on opportunities for others to have these experiences, due to not feeling as constrained to disciplinary norms as their campus peers. TF, meanwhile, attributed greater value to discipline porosity, as they recognized that those “opportunities” could never be sustained, in the academy at least, without some type of disciplinary transformation. Alternatively, RS placed a lower value on both, as their positions did not empower them to take what they saw as risks associated with science that looked unconventional. The following is a representative quote that expresses this sentiment:

“I have no problem engaging in citizen science or including non-university experts on grant-funded research that I’m leading. But I also can’t afford to take risks that might threaten a grant proposal from being funded. […] The precarity of my job limits how I practice collaboration.” (RS #7)

Discussion: institutional context matters

Each respondent expressed concerns over the state of the world and a desire through their research to have a positive impact on it. Yet how these shared concerns were put to work through research and scholarship often varied depending on their institutional locations. In other words, titles—which are a proxy for social location—mattered when it came to understanding what “good” solutions-oriented, collaboration research looked like. We would do well to understand this, as opposed to talking about wicked problems with scholarship in higher education as something that looks, feels, and is valued the same for all researchers involved. This finding also helps ground calls for more and better training to support this type of research (Kawa et al. 2021), realizing that curricular changes do nothing to change these institutional realities.

While this study is novel, its findings point to challenges, tensions, and incentive structures that have been broadly identified by others. Similar points were raised famously in the 1980s, for instance, as part of a larger conversation about the role of higher education in the US. Key constituencies of this conversation included university faculty, citizens, and lawmakers, who called into question the direction, role, and values of the academy. The Carnegie Foundation for Teaching, under the leadership of Ernst Boyer, emerged as a leading voice during this period (Boyer, 1987; Boyer Commission, 1998). Boyer challenged the priorities of public universities:

“Increasingly, the campus is being viewed as a place where students get credentialed and faculty get tenured, while the overall work of the academy does not seem particularly relevant to the nation’s most pressing […] problems” (Boyer Commission, 1998, p. 14).

While painting a critical picture of disciplines the data do not condemn them. The number of discipline-based doctorate degrees awarded worldwide continues to increase (OECD, 2016), with more than 55,000 being awarded annually in the US alone (NSF, 2021). The data presented in the prior section need not be read as critiquing disciplines, assuming disciplines can exist without being so disciplining. The data are hopeful in this sense. They show remarkable variability across higher education for fostering different research-directed incentives and rewards, which, to some degree, appear to exist irrespective of the disciplines involved. The fact that what counts as “good research” varies considerably across the five groups highlights that discipline is not destiny.

The data are also useful as they show the dangers of making overgeneralizations about wicked problems in scholarship in the academy. One of the paper’s more novel contributions is its sensitivity to how higher education is composed of multiple institutional, research-oriented standpoints, each nested in a unique set of social networks, resource flows, and power differentials. When we talk about needing to foster interdisciplinary, collaborative research (e.g., Kawa et al., 2021; Simons et al., 2022), the data remind us to modify that call by adding “for who?” As described in the prior section, the verb to foster has different meanings depending on one’s position within the academy.

This research is also unique for including ES, which gives an opening to study an understudied and thus all-too-invisible institutional standpoint relative to more familiar research roles in R1 universities. Those with PhDs employed by extension and engagement units at Land Grant Universities do not have to have to worry about, for example, the publishing treadmill (Van Dalen and Henkens, 2012), which we know from the above discussion can disincentivize stakeholder-engaged research collaborations. At the same time, ES faced its own institutional constraints. For instance, the metaphor of the siloed university can be extended to talk about the separation between academic departments and colleges and the extension and engagement “arm” of Land Grant Universities. This campus-field separation has been known to afford not only a physical separation between university positions but a cultural segregation as well, which can lead field-based ES feeling unconnected from, and even undervalued by, campus-based teaching and research peers (Thompson and Lamble, 2000).

Realizing how incentive structures in higher education differ is not in itself a solution to fostering solution-oriented, collaborative research. Yet this knowledge can be effectively utilized by research administrators and principle investigators interested in creating opportunities for collaboration that are sensitive to the “local” realities of each of the five positions studied. Toward that end, this research has practical applications as the challenges and outcomes/rewards identified speak concretely to the lived experience of the positions interrogated.

The data suggest numerous practical applications, which include the following.

-

Rethinking what “counts” (e.g., relationship building, non-academic forms of communication, co-/stakeholder-authored publications) in the annual review process to better support collaborative, solution-oriented scholarship.

-

Institutionalizing multi-year “rolling averages” in annual evaluations to capture the time horizon of collaborative research, realizing it takes time it to build relationships and trust and to cultivate the skills to communicate across and between disciplines and stakeholders.

-

Creating research positions that are institutionally embedded in both town and gown. While respondents in ES positions worked for a university they did not work on campus, residing instead in the communities they served—an institutional location that greatly reduced the transaction costs associating with building social capital and trust with community stakeholders.

-

Intentionally supporting opportunities for individuals to build diverse collaborative research networks. This support could include, for example, making available university monies to pay for travel and room and board to physically foster these connections, allowing attendance of these events to “count” during annual evaluations and/or tenure and promotion, providing momentary incentives for participation (e.g., making available professional development money in exchange for attendance), etc.

-

Normalizing expectations that signal institutional support for wicked problems scholarship, such as during the recruitment, onboarding, and orientation processes. Institutional norms and cultures cannot be expected to change overnight. Yet transformational seeds can be planted if new hires are encouraged to reimagine what it means to practice “good” collaborative scholarship and taught to feel that they are at a place that supports such disruptive thinking and doing.

The study has several limitations. While the total “n” is 44, I am ultimately trying to draw conclusions across five different groups. The “n” for each group varies from 7 to 10. While interviews continued until theoretical saturation was reached (Guest et al., 2020), further research is needed to establish the robustness of the conclusions given the relatively small “n” for each standpoint. It is worth remembering that all respondents were in universities based in the US. Whether this methodological fact impacts the study’s generalizability is for future (comparative) research to decide. All respondents were involved in solutions-oriented, collaborative scholarship at the FEWs nexus. Would the findings look different if participants studied other wicked problems—e.g., corporate crime, state terrorism, species extinction, population, abortion, Covid-19, immigration, war/conflict? This question is for future research.

Conclusion

Much has been written about our need to teach and train the next generation of researchers to tackle the world’s wicked problems (e.g., D’Agostino and Santus, 2022; Kawa et al., 2021; Simm et al., 2021). Yet this focus depoliticizes the conversation and fails to ask the more critical questions that place the institutional practices, norms, and motivates of higher education in the crosshairs. Is higher education structurally and culturally capable of supporting solutions-oriented, collaborative research? Knowing scholars in higher education hold diverse titles, and that the distribution of those titles is shifting (e.g., the neo-liberalization of higher education has ushered a shift from permanent to at-will contracts), what does “good” collaborative research look like across these different social locations? The novelty of this paper lies in its ability to empirically address such questions.

The findings confirm that one’s institutional position matters immensely in shaping what collaborative research looks like for individuals in that role in terms of outputs/rewards and challenges identified. Even among those committed to collaborative, solutions-oriented scholarship, institutional positions and the norms, practices, and processes linked to those roles greatly shaped the type of research that respondents were able to do and who they ultimately collaborated with. The data presented give research administrators, university leadership broadly, and principle investigators concrete insights into how to better incentivize, support, and reward solution-oriented, collaborative research for all scholars in higher education.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as respondents were promised during informed consent that data generated from the study would not be shared, except in the context of publications where the author could ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

References

Albert M, Paradis E, Kuper A (2017) Interdisciplinary fantasy: Social scientists and humanities scholars working in faculties of medicine. In: Frickel S, Albert M, Prainsack B (eds) Investigating interdisciplinary collaboration: theory and practice across disciplines. Rutgers University Press, Rutgers, NJ, pp. 84–103

Ball SJ (2012) Performativity, commodification and commitment: an I-spy guide to the neoliberal university. Br J Educ Stud 60(1):17–28

Bandola-Gill J, Arthur M, Ivor Leng R (2022) What is co-production? Conceptualising and understanding co-production of knowledge and policy across different theoretical perspectives. Evid Policy 19(2):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16420955772641

Becher T, Trowler PR (2001) Academic tribes and territories. The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

Berg LD, Huijbens EH, Larsen HG (2016) Producing anxiety in the neoliberal university. Can Geogr/Géogr Can 60(2):168–180

Bourdieu P (2004) Science of science and reflexivity. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Bowman S, Salter J, Stephenson C, Humble D (2022) Metamodern sensibilities: toward a pedagogical framework for a wicked world. Teach High Educ 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2151835

Boyer EL (1987) College: the undergraduate experience in America. Harper & Row, New York

Busch L (2017) Knowledge for sale: the neoliberal takeover of higher education. MIT Press., Cambridge. MA

Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University (1998) Reinventing undergraduate education: a blueprint for America’s research universities. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED424840.pdf

Canaan J, Shumar W (eds) (2008) Structure and agency in the Neoliberal University. Routledge, New York

Carolan M (2022) A decent meal: building empathy in a divided America. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Carolan M, Hale J, Bjørkhaug H, Dwiartama A, Hatanaka M, Hiraga M, Legun K, Loconto A, Wolf S (2023) A front porch for critical agrifood studies: engagement across the “food system” boundaries. Int J Sociol Agric Food https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v28i2.504

Cook KS, Hegtvedt KA (1983) Distributive justice, equity, and equality. Annu Rev Sociol 9(1):217–241

D’Agostino L, Santus D (2022) Teaching geography and blended learning: interdisciplinary and new learning possibilities. AIMS Geosci 8(2):266–276

Derricourt R (2012) Peer review: fetishes, fallacies, and perceptions. J Sch Publ 43(2):137–147

Di Leo JR (2020) Catastrophe and higher education: neoliberalism, theory, and the future of the humanities. Palgrave Macmillan, London

D’Odorico P, Davis KF, Rosa L, Carr JA, Chiarelli D, Dell’Angelo J, Gephart J, MacDonald GK, Seekell DA, Suweis S, Rulli MC (2018) The global food–energy–water nexus. Rev Geophys 56(3):456–531

El-Zein AH, Hedemann C (2016) Beyond problem solving: engineering and the public good in the 21st century. J Clean Prod 137:692–700

Evis LH (2022) A critical appraisal of interdisciplinary research and education in British Higher Education Institutions: a path forward? Arts Humanit High Educ 21(2):119–138

Falkenberg RI (2021) Re-invent yourself! How demands for innovativeness reshape epistemic practices. Minerva 59(4):423–444

Fawcett J (2013) Thoughts about multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary research. Nurs Sci Q 26(4):376–379

Friedman, M (1970) The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. N Y Times Mag 32. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html

Gavazzi SM, Gee EG (2018) Land-grant universities for the future: higher education for the public good. Johns Hopkins University Press

Goodkind S, Zelnick JR, Kim M, Harrell S (2023) Caught in the neoliberal churn: pushing back against “productivity” as a measure of impact. Affilia 38(3):345–349

Guest G, Namey E, Chen M (2020) A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 15(5), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Guler S, Tuzunoglu Y (2019) Academic alienation and marketization of scientific production: a study on business and management discipline. J Politics Econ Manag 2(1):55–64

Hanson M, Barreiro P, Crosetto P, Brockington D (2023) The strain on scientific publishing. Policy Commons, USA

Harvey D (2005) A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hou X, Li R, Song Z (2022) A bibliometric analysis of wicked problems: from single discipline to transdisciplinarity. Fudan J Humanit Soc Sci 15(3):299–329

Jasanoff S, Simmet H (2017) No funeral bells: public reason in a ‘post-truth’age. Soc Stud Sci 47(5):751–770

Kawa N, Arceño M, Goeckner R, Hunter C, Rhue S, Scaggs S, Biwer M, Downey S, Field J, Gremillion K, McCorriston J (2021) Training wicked scientists for a world of wicked problems. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00871-1

Koch S, Tetley C (2023) What ‘counts’ in international forest policy research? A conference ethnography of valuation practice and habitus in an interdisciplinary social science field. Forest Policy Econ 154, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2023.103034

Krause KL (2012) Addressing the wicked problem of quality in higher education: theoretical approaches and implications. High Educ Res Dev 31(3):285–297

Leydesdorff L, Ivanova I (2021) The measurement of “interdisciplinarity” and “synergy” in scientific and extra‐scientific collaborations. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 72(4):387–402

Lönngren J, Van Poeck K (2021) Wicked problems: a mapping review of the literature. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol 28(6):481–502

McCune V, Tauritz R, Boyd S, Cross A, Higgins P, Scoles J (2021) Teaching wicked problems in higher education: ways of thinking and practising. Teach Higher Educ 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1911986

McGreevy SR, Rupprecht CD, Niles D, Wiek A, Carolan M, Kallis G, Kantamaturapoj K, Mangnus A, Jehlička P, Taherzadeh O, Sahakian M (2022) Sustainable agrifood systems for a post-growth world. Nat Sustain 5(12):1011–1017

Moore K, Kleinman D, Hess D, Frickel S (2011) Science and neoliberal globalization: a political sociological approach. Theory Soc 40(5):505–532

New Faculty Majority (2021) Facts about adjuncts new faculty majority. New Faculty Majority, Akron, OH

Nietzel M (2021) Movin’ on up: nine universities climb to highest Carnegie classification In (2021) Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeltnietzel/2021/12/21/movin-on-up-nine-universities-climb-to-highest-carnegie-classification/?sh=2096d5c84d8b

NSF (2021) Doctorate recipients from U.S. universities. National Science Foundation, Washington, DC

NSF (n.d.) Academic R&D in the United States. National Science Foundation, Washington DC

NVivo (2015) Qualitative data analysis software, version 11. QSR International Pty Ltd

OECD (2016) OECD science, technology and innovation outlook 2016. OECD Publishing, Paris

Proctor K, Tabatabaie SM, Murthy GS (2021) Gateway to the perspectives of the food–energy–water nexus. Sci Total Environ 764, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142852

Rittel H, Webber M (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 4(2):155–169

Saldaña J (2013) The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 2nd edn. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, CA

Scholz RW (2020) Transdisciplinarity: science for and with society in light of the university’s roles and functions. Sustain Sci 15:1033–1049

Shermer ET (2021) What’s really New about the Neoliberal University? The business of American education has always been business. Labor 18(4):62–86

Simm D, Marvell A, Mellor A (2021) Teaching “wicked” problems in geography. J Geogr High Educ 45(4):479–490

Simons M, Goossensen A, Nies H (2022) Interventions fostering interdisciplinary and inter-organizational collaboration in health and social care; an integrative literature review. J Interprof Educ Pract 28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100515

Stankevičienė J, Kraujalienė L, Vaiciukevičiūtė A (2017) Assessment of technology transfer office performance for value creation in higher education institutions. J Bus Econ Manag 18(6):1063–1081

Sztompka P (1999) Trust: a sociological theory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA

Thompson G, Lamble W (2000) Reconceptualizing university extension and public service. Can J Univ Contin Educ 26(2). https://doi.org/10.21225/D53P4F

Turner VK, Benassaiah K, Scott W, Iwaniec D (2015) Essential tensions in interdisciplinary scholarship: navigating challenges in affect, epistemologies, and structure in environment–society research centers. High Educ 70(4):649–665

Van Dalen HP, Henkens K (2012) Intended and unintended consequences of a publish‐or‐perish culture: a worldwide survey. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 63(7):1282–1293

Wade AA, Grant A, Karasaki S, Smoak R, Cwiertny D, Wilcox AC, Yung L, Sleeper K, Anandhi A (2020) Developing leaders to tackle wicked problems at the nexus of food, energy, and water systems. Elem Sci Anthr 8:11. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.407

Ylijoki OH (2022) Invisible hierarchies in academic work and career-building in an interdisciplinary landscape. Eur J High Educ 12(4):356–372

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The sole author is responsible for all aspects.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Colorado State University (ethics approval number: 2279).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carolan, M. Do universities support solutions-oriented collaborative research? Constraints to wicked problems scholarship in higher education. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 382 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02893-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02893-x