Abstract

One of the primary requirements of a democratic media is to represent the interests of different social groups in the society it seeks to serve. Since the dominant class invariably has control over the media industry, media outputs typically reflects its own viewpoints or perspectives. Using a content analysis method this study discusses the invisibility and under-representation of class identity and examines news coverage of the automotive and glassware workers’ strikes and the class-based issues in Turkey. We attempt to reveal the under-representation of class identity and how the media constructs a dominant ideology in capitalist societies, including how class identity is excluded from the mainstream media in the case of Turkey. Our findings reveal that class identity has been under-represented in the news media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The theorists of postmodernity and late modernity have argued that class identity has declined in importance. The emphasis on social identity also reflects the processes of post-modernization and globalization in which identities are increasingly complex, contested and no longer singularly reducible to class or occupation in any straightforward fashion. The concept of class is derived from economic distinctions bound up with the social relations of production (“you are the job that you do”), which is dominated by the “work-based society”. Certain significant developments, which have occurred within the social sciences, have had a profound impact on the analysis of social inequality. These developments are as follows: the new theoretical approaches and perspectives such as feminism, post-structuralism, and postmodernism; the “cultural turn” from understanding social inequality through economics and politics towards symbolic representations of cultural difference (Butler and Watt, 2007). The conceptualization of difference has become the central discursive element of postmodern politics. Postmodernism involves western notions of internationalism, multiculturalism and social pluralism. Difference and diversity have formed the basis for more radical theories of democracy, especially through new communication technologies. Recent political theory has moved towards an acknowledgement of the significance of culture, identity and the personal dimensions of democracy and political expression. The promises of postmodernism -choice, diversity, multiculturalism, individualism, and sexual liberationism- have become the core of contemporary cultural politics (Lewis, 2008, p 211, p 238).

Aronowitz (1992) points out that the working class is increasingly invisible in public representations. Rather, other subject-positions such as gender, ethnicity, disability, and sexual orientation have been replaced with the class identities that previously dominated the economic, social, and political landscape. Meiksins Wood (1998) also sees the discourses of the disappearance of class as “today’s intellectual fashion” and discusses the present impasse in post-left political thinking and the return to class politics. The absence of explicit class discourses does not mean the absence of class realities, and their effects in shaping the life-conditions and consciousness of the people who come from a different “field of force”. If the class situations and oppositions are not directly mirrored in the political domain, people will not be able to have class interests or to express these interests politically.

The media have a contradictory role regarding class power. They do predominantly carry corporate and state-friendly messages, but not exclusively. They do have a role in legitimizing capitalist social relations. What is the role of the media in the reproduction of class power? The media have a role in promoting dominant ideologies and in spreading them variably amongst different sections of the population. The media can, on occasion, help to convince elements of the public of states of affairs and evaluations of them, which are thoroughly ideological, even where this is not in their interests. However, the media also have a direct role, which is arguably as important for the reproduction of inequality as ideological power over the masses. Furthermore, there are a variety of mechanisms and practices in society, by which power is exercised and resources are distributed, in which the media have a minimal role (Miller, 2002, p 245, p 259). Dencik and Wilkin (2015) point out the antagonistic relationship between mainstream media and the labor movement. Due to the oppositional standing of the labor movement, it has been destroyed, curbed or seen as a threat by those who have economic privileges, so it has faced with many challenges. By the end of the twentieth century, the labor movement retreated and lost its community links and the working-class culture around the world. In this context, the control of the media representations of the social reality means to an attempt to control how people’s thoughts about the social world.

One of the primary requirements of a democratic media system is to represent the interests of different social groups in society. Indeed, since the dominant class has control over the media industry, media content typically reflects their own viewpoints. The aim of this study is to discuss the invisibility and under-representation of class identity based on the cases of automotive and the glassware workers’ strikes, and the news coverage of class-related concepts. For this aim, the study examines the online mainstream newspapers (Hürriyet, Milliyet, and Habertürk) and a left-wing newspaper (Birgün), and analyzes the tone of online news concerning the worker strikes of glassware and automotive industries by using the content analysis method. Thus, this study attempts to reveal under-representation of class identity and how media constructs a dominant ideology in capitalist societies and to illustrate how class identity is excluded from the mainstream media.

The decline of class identity during the era of neoliberalism

Many writers have suggested that as we move from an industrial to a post-industrial society, traditional social identities such as class will decline in terms of social significance. Pakulski and Waters (1996, p 1–3), for example, have argued that with the declining commitment to Marxism, the collapse of Soviet communism, the waning appeal of socialist ideologies in the West, the concept of class is losing its ideological significance and its political centrality. Both the right and the left have abandoned their preoccupation with class issues. While the right has turned to morality and ethnicity, the critical left has focused on issues of gender, ecology and human rights. Accordingly, class is primarily related to economic-productive determination; that is, it is based on property and market relations. A society in which such economically caused social clustering occurs, and where these clusters are the backbone of the social structure, is a class society. In such a society, class involves a measure of self-recognition and self-identification, and the difference between “them” and “us” becomes a necessary condition for the formation of class actors. The new political order, which is a result of the shrinking state and the erosion of left-right polarity, has created new political actors and displaced the class society.

Balibar (1991, p 156–157) has also argued that class struggle in the capitalist world has disappeared from the scene, and classes themselves have lost their visible identity in the most significant political arenas. Balibar (1991) says:

Their identity has come more and more to seem like a myth that has been fabricated by theory, and projected on to real history by the ideology of organizations (primary workers’ parties) and more or less completely internalized by heterogeneous social groups. The proletariat no longer exists. Even if exploited labor and finance capital are still with us, classes and class struggle turn into political myth, and Marxism itself into mythology (pp 156–157).

Fraser (2000) also indicates that issues of recognition and identity have become even more central, and the character of identity struggles has changed. According to Fraser (2000), today’s recognition struggles emerge at a moment of hugely increasing trans-cultural interaction and communication, when accelerated migration and global media flows are hybridizing and pluralizing cultural forms. This move from redistribution to recognition also occurs despite -or because of- an acceleration of economic globalization. The culturalist proponents of identity politics reverse the claims of an earlier form of Marxist economism. They allow the politics of recognition to displace the politics of redistribution, just as Marxism once allowed the politics of redistribution to replace the politics of recognition.

The concept of class identity refers to the individuals’ interests, tastes, attitudes, and dispositions linking to their socio-economic class position. Today, it is argued that more individual lifestyle identities displace class identities. Moreover, the left-wing parties focus on the inequalities stemming from cultural identities rather than class status. Whereas active class-based social and political movements were carried out in the early and mid-20th century, today, Union membership and strike rates are on the decline and even destroyed. The fact that class-based issues are refused does not mean that class is no longer critical. The persistent and rising levels of socioeconomic inequality, declining class mobility and low-wage policy show that class is still an important matter (Eidlin, 2014).

Petras (2015a) has also pointed out the concept of “non-leftist left”. The new political movements, purportedly on the left, no longer are based on class-conscious workers nor are they embedded in the class struggle. In place of the traditional class-based left, ‘non-leftist left’ movements have emerged. Imposing regressive class-based “austerity” on their populations debilitate the trade unions and collective action. According to Petras (2015b), austerity is one of the most important reasons of the decline of class-consciousness. ‘Austerity’ means defending the class interests of the bourgeoisie. The neo-liberal right consistently displaces working class organizations, whereas the ‘hard right’ surrounds the working class with a nationalist-chauvinist consciousness.

Today, the decline or the transformation of left-wing politics has grounded that class-consciousness is no longer a central feature of contemporary class relations. The modern contours of class division have altered from a stable tripartite system of social classes namely upper, middle, and working classes, to a more fragmented class structure. Class divisions still exist, but they are no longer so easily mapped into a tripartite imagery of social classes. The lines of types property and employment relations are not clear enough to define them. Although people may no longer see class identities as ways of describing themselves and may not engage in collective or class-based action, economic divisions of class have persisted and even deepened (Scott, 2013).

The changing structure of class is closely related to changing work patterns. The organization of workers is also a political process. The political dimension works on two axes: the development of unions and ways of economic production and philosophies of workers’ rights. On the other hand, the increasing individualism of societies has also brought immense changes to the understanding and organization of work. During the industrial period, while a collective factory-based workforce could organize to lobby for improved working conditions through the trade union movement, the emergence of a neoliberal global economy has undermined the organized working class with flexible working and workplace deregulation (Wessels, 2014). Stable identities based on social class hierarchies have been replaced with multiple, fragmented and more uncertain identity projects based on “life-style” and consumer choices; and religious, ethnic and national identities are also seen as characteristic of contemporary life. Individualization is said to undermine perceptions of common fate, mutual dependence, trust and long-term commitments, along with robust associations between class-consciousness, sense of identity and collective action (Wetherell, 2009, p 1–5).

In Turkey, from the end of World War II to the military coup of 1960, important structural changes (industrialization, urbanization, etc.) were experienced. During this time, the working class of Turkey began to be formed as a new political identity and was underpinned by the labor unions in the 1960 and 1970s (Özden, 2011). The emergence of the working class as a force on Turkey’s political scene dates back World War II. In the 1940s, organized forms of this class and trade unions also made their appearance. In the 1960s, along with economic development, the sociopolitical sphere gained a notable dynamism. In addition, socialist publications and discussions were multiplied, and strikes were legalized. These developments had impacts on the working class. The working class transformed into a very aggressive and highly organized sector. The number of unionized workers increased. Strikes spread around larger numbers of employees and were more prolonged, particularly in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. After 1982, when the new constitution came into force, the law has restricted the establishment of new trade unions and the right to strike (Margulies and Yildizoğlu, 1984).

Dogan (2010) points that the post-1980 political and economic transformations have aimed to install market rationality based on profit-maximizing behavior and to restrict the right to unionize and strike, and argues that the privatization of state-economic enterprises under the Özal administration of the 1980s undermined the fundamental political and economic acquisitions of the workers in state-economic enterprises in the 1960s and 1970s. Coşkun (2012) also notes that the pre-1980 period had important features regarding class-consciousness and culture. For instance, self-governing experiences were implemented in factories and mines during this period. It meant that the labor organizations made their own decisions within the self-governing bodies. On the other hand, the 1980s have characterized the integration of Turkey to the world economy and the decline of state intervention in the economy. Also, the working class became no longer a part of the political system.

A structural transformation process was initiated in the 1980s with the free-market economic policies of the Özal administration. The Turkish state reduced public spending on services such as education, healthcare, and social security, resulting in their deterioration. During the 1990s, market-oriented policies were continued. In the 2000s, the AKP administration also maintained neoliberal economic policies leading to further consolidation of this mode of capital accumulation (Balkan et al., 2017). Along with Turkey’s transition to neoliberalism since the 1980s; trade liberalization, financialization, and privatization have led to widespread de-unionization and precariatization of labor. Moreover, in the 2000s, anti-labor regulations have consolidated flexible forms of labor and the Islamic aid networks, which were founded and strengthened during the AKP period, also helped to pacify the class-consciousness of Turkish working class (Gürcan and Mete, 2017).

Mello (2010) points out that the labor movement in Turkey has never received as much attention as other oppositional social movements. According to Mello (2010), the predominant view of the labor movement in Turkey is one that sees the movement as relatively inconsequential to the development of Turkish state-society relations. This view is based on three reasons: first, the notion that the state granted labor rights and freedoms without a protracted struggle, second, the idea that the military coup of 1980 crushed the Turkish labor movement, and finally, the belief that the Turkish labor movement was hampered by internal divisions resulting from abstract theoretical debates. Coşkun (2012) has analyzed the various tones of class-consciousness among the mine and textile workers and discovered that the solidarity and resistance tendencies are seen among the workers relatively, and they defend the fundamental values such as justice and equity. However; he has also indicated that the working class has not expressed themselves by using class-based concepts, had a weak class perception, and adopted Islamist values and attitudes.

Tillman (2014) notes that although AKP has parallels with mainstream center-right parties in Europe, its supporter base is built on working-class voters. Tillman also draws attention to a contradiction on the real basis of mass support of AKP. In other words, the working class instead of middle-class voters supports the AKP as a right wing and conservative party. The AKP government holds the support of working-class voters due to its religiously conservative style, as well. As noted by Winlow and Hall (2013), the political representation issue of the working class has also emerged in the neoliberal era. It should be questioned why many working and non-working poor people vote for neoliberal political parties that create policies directly antagonistic to their class interests. The fundamental issue here is that traditional working-class is no longer politically represented.

Media representations of the working class

Emerging changes in the theoretical perspectives and the practices of the capitalist system have impacted the framing of media and the production of meaning. According to Dworkin (2007, p 63–65), in the 1980s and 1990s, class theory and analysis –and more generally social approaches– came under serious attack. They were being critiqued not only by the usual suspects –conservatives and neoliberals– but also by leftist scholars, including those in various stages of abandoning Marxism but still committed to the radical projects of participatory democracy. For critics, the transformations undermined the viability of the class narrative and the privileged position given to the working class in the making of history. Cultural studies were part of a broader effort to critically evaluate the impact of growing affluence, a spreading mass media, and a burgeoning consumer capitalism on cultural, political, and social life. Accordingly, the cultural was accorded a primary position in the social process itself: it was the realm in which meaning was produced. This perspective represented a critique of the base–superstructure model that portrayed culture and ideology as being reflections of the economic base.

The media, including institutions and contents, are the outcome of dominant forms of economic organization. Since the dominant form of economic structure is capitalism, the media are determined by the capitalist mode of production. Accordingly, media do act like a private company and focus on the maximization of profit. Also, media contents are seen as ideologically supporting the dominant and ruling classes. Media companies tend to lean towards an oligopolistic model and are controlled by a few corporations. As a result, it is hard to find alternative views in the media. According to this Marxian perspective, the media excludes alternative views (Siapera, 2010, pp 66–67). For Marxists, class struggle gains meaning when it becomes “class for itself” than “class in itself”. If the ruling class is so powerful that it dominates all other ideas, then there can be no oppositional working-class consciousness, no possibility of “class for itself”. The idea of class-consciousness in Marxism is concerned with ideology. According to Marx’s ideology theory, “life is not determined by consciousness, but consciousness by life” (as cited in Milner, 1999, p 25, p 27).

According to Couldry (2010, p 82–88), in a neoliberal democracy, the media form is harmonized with neoliberal governments’ particular expectations of their subjects and the general features of the neoliberal social landscape (increasing inequality, intensification of class differences, and so on). The outcome is not a simple reinforcement of neoliberal values, let alone an explicit reproduction or legitimization of neoliberal doctrine. Media do not encourage the development of a counter-rationality to neoliberalism. Market rationality has been universally embedded in political theory and administrative practice, and the building of a ‘counter-rationality’ to neoliberalism or an alternative rationality is not discussed. Neoliberal rationality is profoundly flawed as an economic model, and the politics in neoliberal democracies has been thoroughly corroded, with negative consequences for social life. Media do operate today in ways that reinforce explicit neoliberal values and their wider corrosion of political life while market conditions in the media sector undermine many resources for critical alternatives.

It is accepted that media contribute to political acceptance of inequality and poverty (Curran, 2011, p 37). Coverage of poverty and social inequality by the media is less than other topics. This argument is based on a few reasons. Firstly, the news reports about poverty are much more likely to focus on specific instances of poor people than the causes of poverty or related public policies. Secondly, as the coverage of poverty by the media as a topic is minimized, some poverty stories are marginalized. Mainstream media have very little to say about what gives rise to poverty and inequality. Only a democratic and pluralistic media can represent the interests of all groups within a society. Marxist approaches to media argue that mainstream media that are based on free market conditions are in favor of dominant class interests. Media is a collection of agencies of class control since they are owned by the bourgeoisie or are subject to its ideological hegemony. The media systems in most liberal democracies are not representative. On the contrary, most subordinate interests are under-represented. The free-market approach excludes broad social interests from participating in the control of the mainstream media, and leads to the concentration of media ownership among certain groups. These shortcomings should be considered in terms of necessities of a democratic media. A democratic media system should enable the full range of political and economic interests to be represented in the public domain (see Curran, 1991).

Another issue with relation to class is the lack of class-consciousness among the working-class. The media have a crucial role to maintain and consolidate the capitalist system. Aronowitz (1992) has emphasized the role of media in the weakening of class identity. The media have justified the management’s claim that successes of unions are due to the use of violence. The workers have lost bargaining power in the face of the decline of the workforce due to robotization in the industry and the decreasing proportion of union members within total employment. The new system, called “disorganized capitalism”, means that the integration of capital and labor with state is considerably loosened. While workers have become increasingly invisible in public representations nowadays, other subject-positions such as gender, ethnicity, and religion are emphasized much more. Cultural identities have displaced the class in the era of global capitalism.

Class underlies the media industry in a distinctive way. While the real world predominantly consists of working or lower middle classes, the media portray the social world as a place heavily populated by the middle class. In general, news media tend to highlight the issues that are of concern to the middle and upper-class readers and viewers. As a whole, a report reflects the views of the middle and upper class. In such a world, business pages of newspapers flourish, but the media coverage of labor is almost nonexistent. The news represents regular people as consumers, but hardly ever addresses them as workers (Croteau and Hoynes, 2014, p 209–216). As Raymond Williams argued, that the organs of mass communication

‘were not produced by the working people themselves. They were, rather, produced for them by others, often […] for conscious political or commercial advantage’ and for ‘the persuasion of a large number of people to act, feel, think, know, in certain ways’ (cited in Tyler, 2015, p 504).

According to Skeggs and Wood’s research (2008, cited in Tyler, 2015), media forms and genres contribute to the ‘transmission, legitimization, and promotion of the distribution of unequal resources and domination’. Tyler notes (2015) that neoliberal media culture depicts the class inequalities as a consequence of individual choices, in other words, wealth is ‘earned’ and poverty is ‘deserved’. Also, Dobson and Knezevic indicate (2017) that the poverty as one of the parts of the class-based issues is portrayed as an individual problem instead of emphasizing its aspects rooted in economic and political inequality. The mainstream media ignore this social group as an audience. Media framing of social issues has an impact on the public about critical social issues, and the media often reproduce class rhetoric.

The history of labor movements and their relation to the mainstream media has long been viewed as one of antagonism and misrepresentation. Given the oppositional roles of capital and the state, the labor movement has often disseminated socialism-inspired ideas about a society built on principles of mutual aid, cooperation, self-help, and direct action. Thus, the main political and economic institutions target the labor movement and left-wing ideas. The control of language and representations of events through media is also an attempt to control the way in which people think about the social world. With the emergence of neoliberal political and economic movements led by the elite in the 1970s, it is the US model of commercial profit-seeking media that has now become the global norm, displacing public service models (Dencik and Wilkin, 2015, p 11–14).

Tracy (2004) has analyzed the overall print news coverage of the American Newspaper Guild strike against The New York Times in 1965. The study has concluded that the representation of this strike resembles the coverage of strikes in other industries and suggested that the commercial press’ reportages and the comments are hard as favorable towards union activity or celebratory on the strike’s outcome. Similarly, Lee and Craig (1992) have demonstrated the ideological aspects of the US newspapers’ news-coverage of Polish and South Korean labor disputes. This study has revealed the pro-management/anti-labor framework that operated in the South Korean case. The authors have argued that this frame is the root of the anti-communist filter.

Dursun (2004) has analyzed the constructed frames of working class identity in Turkish press and pointed out an exclusion process, which works by negative word selections. Oğurlu and Öncü (2017) draw attention to the class struggle between the secular and Islamist factions of the Turkish dominant class in connection with the neoliberal transformation of Turkish capitalism to understand the media sector in Turkey, and argue that the ascending Islamist-dominant class faction aims to obtain full control over the media. The authors also identify that the Islamist-dominant class faction intends to take over the secular ruling class newspapers to strengthen their class power in establishing hegemony over the masses and coerce them to adopt their values, and each dominant class faction is struggling for complete access and control over media to ensure their hegemony. The authors’ emphasis is that capitalism continues in the form of neoliberal Islam and also eliminates the critical viewpoints to ever-growing inequities of capitalism.

In Turkey, a few large conglomerates that are interested in non-media-related sectors such as mining, energy, tourism, transportation, insurance, banking, and construction have the media industry in their hands. The fact that these conglomerates depend on government licenses, subsidies, and privatization deals to conduct business in these areas makes them extremely vulnerable to political and economic pressures, and consequently, shapes the editorial policies of their media companies. This kind of relationship between the press and the ruling party is portrayed by the concept of “yandaş media” (partisan media), particularly in the meaning of pro-AKP (Yesil, 2014). The market-driven media system of Turkey carries the traces of the long-standing authoritarian state forms along with globalization and neo-liberalization of the post-1980 era, particularly, about media ownership structure and also conservative and nationalist values system. After AKP came to power in 2002, Islam rose to prominence within the political realm, and the relationships between Islam, secularism, capitalism, and democracy began to change. In addition to this, the dominant role of the state and the controversial relationships between media, political Islam, and neoliberal economic order determine the characteristics of the media (Yesil, 2016).

To understand media and political power relations, the focus should be on freedom of the press by going beyond the liberal understanding. Liberal view sees state intervention to the independence of journalists and the media as the primary threat and disregards concentration of media ownership as a restrictive factor of freedom of the press. Croteau and Hoynes (2014) draw attention to the relationship between political powers and media, and argue that it leads to some concerns related to an informal political pressure on different social groups. According to the report of Freedom House (2016), press freedom status of Turkey has been determined as “not free.” The report has emphasized that media ownership remains concentrated in the hands of a few large, private holding companies. Also, the report has pointed out the political pressure related to critical reporting on the AKP government throughout 2015.

Method and findings

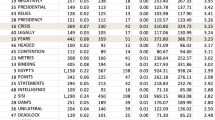

The news media provide certain clues for understanding the power relations within society. In this study, I have employed the descriptive content analysis to describe the characteristics of news reports. In order to analyze the news coverage of class identity and class-based issues, I have examined the online news texts of the center-right and pro-government newspapers Hürriyet, Milliyet, and Habertürk, which are owned by large capitalist groups. Also, I have included radical left Birgün in the analysis to compare two different perspectives concerning class-based issues. Since these online news platforms have adopted a pro-government perspective on the central political axes at the same time, I have chosen them to illustrate under-representation of class identity to reveal the structural bias of mainstream media in favor of the ruling party. For this purpose, I have collected 2249 news articles on the websites of Hürriyet, Milliyet, Habertürk, and Birgün and analyzed the news reports of the second six-month period of 2015 to reveal the low coverage.

Then, I have analyzed the tone of the news about the strikes in the automotive sector in May 2015 and Şişe-Cam’s banned strike actions in May 2017. Since these strike actions provide insight on the representations of class-related issues, they have been chosen as the sample of this research. The results of the study are limited to the research samples. In Turkey, since two general elections were held in 2015 and the political discussions and conflicts between the political parties and different social groups were deepened in the media, the news contents of 2015 were researched. Also, the AKP government in May 2017 banned Şişe-Cam workers’ strikes. As it was an important development restricting the workers’ rights, it was included in the research to analyze the tone of news coverage (Table 1).

This table aims to show the news coverage of class-based issues by comparison. It is seen that the concepts related to class issues and economic rights have more representations in left-wing newspaper Birgün than the others. The under-representation of class-based issues and class identity in the mainstream news media is compatible with the values of global capitalism. Class-based issues such as disorganized working classes through de-unionization, low wages, flexible employment, intensification of workloads, erosion of social benefits and increasing workers’ debts are ignored in the news media.

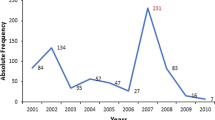

In May and June 2015, a wave of strikes and protests happened in Turkish automotive industry with the participation of thousands of workers. These resistances and protests targeted to major companies in the automotive industry and their suppliers. These strikes and resistance movements were against both the employers and Turkish Metal Union which covers the automotive workers in these factories, and Türk Metal lost a considerable the number of members (Çelik, 2015). Çelik (2015) has emphasized that this strike wave is an uncontrolled industrial movement in the history of Turkish Industrial relations and described as a challenge to the trade union status quo and the mainstream trade unionism which does not take into account the opinions of its members.

In May 2015, more than 2500 workers in a factory run by French carmaker Renault in western Turkey went on strike for wages and benefits. Workers stopped production at the company’s factory in the Bursa province. The strike of this major automotive producer in Bursa spread to Ford Otosan in Kocaeli and some automotive parts suppliers in Bursa. Two factories of Ford Otosan, a long-standing joint venture between the U.S. car giant and Turkish industrial conglomerate Koç Holding, halted production. The strikers had been asking for wage increases. These strikes led to some concerns ahead of elections on June 7 (IndustryWeek, May 15, 2015a; May 20, 2015b). Over 20.000 metal workers in Renault, Fiat, Ford, Türk Tractor and some suppliers initiated strikes in 2015 to protest both the employers union and the labor union. Also, in Mercedes and some other suppliers, employees launched different forms of protests to raise their joint demands (Korkmaz, 2015) (Table 2).

In order to classify the news contents, I have utilized three categories; critical, neutral, and supportive. Within the context of this study, being supportive has been coded as supporting the strikes and workers, while being critical has been interpreted as criticizing the strikes. Hürriyet reported the strikes from a framework based on the viewpoint of the ruling party by referring to the Deputy Prime Minister saying, “The timing of the action is noteworthy.” (20 May 2015). Similarly, Milliyet cited the views of employer representatives’ and the influences of the strikes on suppliers.

Habertürk reported that the strikes caused a loss of 50 million dollars and that Minister of Economy evaluated the economic effects of the strikes on the automotive sector negatively. Habertürk showed that it focused on the economic outcomes rather than the workers’ rights by using the title, “Production was stopped once more at a factory!” (25 May 2015). Also, it drew attention to the cost of the strikes on the employers with the title, “Here’s the bill for 1-month of strike!” (21 May 2015).

Birgün reported the strikes with a supportive tone. Furthermore, the volume of news coverage was higher than other newspapers, and the news content was constructed from the perspective of the labor side. The news titles reflecting the voice of the workers are as follows:

“Workers are not deceived: We draw our strength from being right” (22 May 2015).

“Resistance grows despite the bosses’ ploys, resignations from the yellow union continue” (26 May 2015).

“Renault workers said ‘no’ to the weak offer. Resistance will continue…” (26 May 2015).

Those who are chosen as primary definers are as important as the tone of the news to construct news frames. The term ‘primary definers’ is used to refer to the figures or authority that the media look first to, such as politicians, professors, and senior managers. By doing this, the media aim at reproducing the ‘existing structure of power’. Thus, the news is encoded through organizational factors, news values, and the use of primary definers (Procter, 2004). As Cushion notes (2015, p 122), political actors are the dominant players in news reporting generally; but, other potential actors, from NGOs to academics, have limited spaces. Hall et al. (1978) argue that the media do not merely and transparently report events according to being newsworthy, and news is a complicated process based on a systematic selection. Hall et al. (1978) draw attention to the primary and secondary definers of the report. Accordingly, the media are largely capitalist-owned. Therefore, the press reproduces the definitions of the powerful, and this leads to a crucial distinction between primary and secondary definers. Notably, the accredited representatives of major social institutions, MPs, and ministers are acknowledged as the definers of social reality for political topics, whereas employers and trade union leaders are acknowledged as the definers of social reality for industrial matters.

This research has shown that the mainstream media in Turkey reproduce the status definitions of political and trade union elites. Whereas Birgün has given priority to the workers’ rights and demands, the pro-government and capital media have criticized the strike wave explicitly or implicitly and reported them by the arguments of the ruling party.

Turkish government banned glassware workers’ strike due to the threat to national security on May 22, 2017. Glassware workers reacted to the ban in 9 factories and workplaces of Şişecam to protest the ban decision and talked about their economic hardship. The workers of Şişecam, Turkey’s most prominent glassware company, would have launched a strike on May 24 with their trade union, Kristal-İş (Sol International, 2017). IndustriALL, a global union representing 50 million workers in 140 countries in the mining, energy and manufacturing sectors, indicated that this was a misuse of the labor law, which did not have any rational or legal base, and suggested that the government was favoring business interests rather than protecting the rights of workers (Industriall, 2017). Despite being banned by the decision of the AKP government, glassware workers continued their strikes. In this context, there is no news coverage on this matter within the research samples (Table 3).

The news coverage of the banned strike of Şişe-Cam was represented at a very low level in the news media. Hürriyet and Milliyet covered the banning of the strike through a neutral tone with only a single report. In addition, Birgün also covered two news reports, but they contained critical evaluations against the government regarding the decision of banning the strike. In general, this development is very important for the future of the workers since it sets an example for possible strike attempts in the future. The absence of the news reports on this issue in mainstream news media has illustrated that the working class and workers’ rights are excluded from public discussions and disregarded. While the news media are supposed to create a forum for public discussions, they have ignored debating and talking about the fundamental welfare rights of workers.

Conclusion

Class allows for mapping economic forms of inequality that invade people’s lives in a way that no other concept makes possible. Class also provides a means of discussing manifestations of politics, culture, and language that neither status nor gender nor race allows (Dworkin, 2007, p 222). Media representations are increasingly determined by different social contexts on a global scale. Power relations are encoded in media representations, and media representations in turn produce and reproduce power relations by constructing knowledge, values, conceptions, and beliefs (Orgad, 2012, p 25). The political economic argument asserts that media economics is driven by logic of capitalism and a pursuit of maximum profit. The findings of this study also seem to be compatible with this view. Class-based discussions in media, society, and politics are seen as “out of date” and this is closely related to the increase of cultural identities in postmodern politics. This viewpoint leads to focusing on the ideological struggle aspect of media, instead of the ownership of the means of production. Media reproduce the definitions of the powerful.

The findings of this study illustrates that news coverage of concepts related to class-based rights, and social inequalities is not sufficient for the debate in the public sphere, these issues are largely ignored by the mainstream news media, and class identity is underrepresented. It is seen that mainstream media are highly aligned with the mindset of capitalism. When media construct social reality, news content is not independent of power relations within society. In Turkey, it is seen that egalitarian values and inequality issues have not been included in the news content in the mainstream news media, which are also pro-government.

The media should provide an open forum to reflect different public views and an inclusive platform for public debate to contribute to the development of a pluralist democracy in society. In Turkey, it can be said that left-wing politics and class identity are underrepresented in the mainstream media as a result of the relationship between media and capitalism. Since Turkish media depend on various forms of advertising and market rules to generate revenue, the poor -and also social inequalities- remain invisible in the news media despite being highly visible almost everywhere. Therefore, the labor movement needs counter-hegemonic platforms to struggle with capitalist dynamics. The emergence of new forms of the digital media will create new opportunities to rebuild the labor movement and class struggle and constitute an environment for the workers’ resistance.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Aronowitz S (1992) The politics of identity: class, culture, social movements. Routledge, New York

Balibar E (1991) From class struggle to classless? In: Balibar E, Wallerstein I (eds) Race, nation, class: ambiguous identities. Verso, London and New York

Balkan N, Balkan E, Öncü A (2017) Introduction. In: Balkan N, Balkan E, Öncü A (eds) The neoliberal landscape and the rise of Islamist capital in Turkey. Berghahn Books, New York-Oxford

Butler T, Watt P (2007) Understanding social inequality. Sage, London

Coşkun MK (2012) Sınıf, Kültür ve Bilinç [Class, Culture and Consciousness]. Dipnot Publishing, Ankara

Couldry N (2010) Why voice matters: culture and politics after neoliberalism. Sage Publications, London

Croteau D, Hoynes W (2014) Media/society: industries, images, and audiences. Sage Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks

Curran J (1991) “Rethinking the media as a public sphere”. In: Dahlgren P, Sparks C (eds) Communication and citizenship: journalism and the public sphere. Routledge, London, pp 27–56

Curran J (2011) Media and democracy. Routledge, Oxon

Cushion S (2015) News and politics: the rise of live and interpretive journalism. Routledge, Oxon

Çelik, A (2015) The wave of strikes and resistances of the metal workers of 2015 in Turkey. vol IV, Issue 10, Centre for policy and research on Turkey (Research Turkey), London, Research Turkey. p 21–37

Dencik L, Wilkin P (2015) Worker resistance and media: challenging global corporate power in the 21st century. Peter Lang, New York

Dobson K, Knezevic I (2017) ‘Liking and Sharing’ the stigmatization of poverty and social welfare: representations of poverty and welfare through internet memes on social media. Ttriple C 15(2):777–795. http://www.triple-c.a

Dogan MG (2010) When neoliberalism confronts the moral economy of workers: the final spring of Turkish labor unions, Eur J Turkish Stud http://ejts.revues.org/4321. Accessed 30 Sept 2016

Dursun Ç (2004) “Türkiye’de İşçi Sınıfı Kimliğinin Medyada Temsili: 1970–1997 [Representation of the working class identity in Turkey: 1970–1997]”, Haber, Hakikat ve İktidar İlişkisi [News, Truth and Power Relationship], Çiler Dursun (ed) içinde, Elips Kitap, Ankara, p 309–353

Dworkin Dennis (2007) Class Struggles. Pearson Education Limited, Harlow

Eidlin B (2014) Class formation and class identity: birth, death, and possibilities for renewal. Sociol Compass 8/8:1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12197

Fraser N (2000) Rethinking recognition. New Left Rev 3:107–120

Freedom House (2016) Freedom of the press. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2016/turkey. Accessed 20 Feb 2017

Gürcan EC, Mete B (2017) Neoliberalism and the changing face of unionism: the combined and uneven development of class capacities in Turkey. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Hall S, Critcher C, Jefferson T, Clarke J, Roberts B (1978) Policing the crisis: mugging, the state and law and order. The MacMillan Press Ltd, London and Basingstoke

Industriall (2017) Turkish government bans glass sector strike. http://www.industriall-union.org/turkish-government-bans-glass-sector-strike

IndustryWeek (2015a) Thousands of renault workers strike in Turkey. http://www.industryweek.com/labor-employment-policy/thousands-renault-workers-strike-turkey

IndustryWeek (2015b) Turkey auto workers strike at ford factory. http://www.industryweek.com/labor-employment-policy/turkey-auto-workers-strike-ford-factory

Korkmaz EE (2015) Unexpected wave of strikes in Turkish automotive industry. Turkey analyses, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung

Lee J, Craig RL (1992) News as an ideological framework: comparing US newspapers’ coverage of labor strikes in South Korea and Poland. Discourse Soc 3(3):341–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926592003003004

Lewis J (2008) Cultural studies: the basics. Sage, London

Margulies, R and Yildizoğlu, E (1984) Trade unions and Turkey’s working class. Middle east research and information project, vol. 14, http://www.merip.org/mer/mer121/trade-unions-turkeys-working-class. Accessed 27 May 2017

Meiksins Wood E (1998) The retreat from class: a new “true” socialism. Verso, London and New York

Mello, B (2010) (Re)considering the labor movement in Turkey. European Journal of Turkish Studies http://ejts.revues.org/4305. Accessed 28 May 2017

Miller D (2002) Media power and class power: overplaying ideology. Socialist register 2002: a world of contradictions 38:245–264

Milner AJ (1999) Core cultural concepts: class. Sage, London

Oğurlu A, Öncü A (2017) The Laic-Islamist Schism in the Turkish dominant class and the media. In: Balkan N, Balkan E, Öncü A (eds) The neoliberal landscape and the rise of Islamist capital in Turkey. Berghahn Books, New York-Oxford

Orgad S (2012) Media representation and the global imagination. Poltiy Press, Cambridge

Özden, BA (2011) Working class formation in Turkey, 1946–1962. Ph.D. Dissertation, Bogazici University, The Atatürk Institute for Modern Turkish History. http://www.ata.boun.edu.tr/?q=node/115. Accessed 25 May 2017

Pakulski J, Waters M (1996) The death of class. Sage, London

Petras, J (2015a) “The Rise of the “Non Leftist Left”. The radical reconfiguration of southern european politics”, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-rise-of-the-non-leftist-left-the-radical-reconfiguration-of-southern-european-politics/5457335. Accessed 24 Oct 2016

Petras, J (2015b) The demise of incumbents: resurgence of the far right, absence of the “consequential left”, Global Research, http://www.globalresearch.ca/the-demise-of-incumbents-resurgence-of-the-far-right-absence-of-the-consequential-left/5487151. Accessed 24 Oct 2016

Procter J (2004) Stuart Hall. Routledge critical thinkers. Routledge, London

Scott J (2013) “Class and stratification”. In: Payne G (ed) Social divisions. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Siapera E (2010) Cultural diversity and global media: the mediation of difference. Wiley-Blackwell, West Sussex

Sol International (2017) Turkish government bans glass workers’ strike due to ‘threat to national security’. https://news.sol.org.tr/turkish-government-bans-glass-workers-strike-due-threat-national-security-172276

Tillman ER (2014) The AKP’s working class support base explains why the Turkish government has managed to retain its popularity during the country’s protests. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/05/29/the-akps-appeal-to-the-working-class-explains-why-the-turkish-government-has-managed-to-retain-its-support-during-the-countrys-protests/. Accessed 28 May 2017

Tracy J (2004) The news about the news workers: press coverage of the 1965 American newspaper guild strike against the New York Times. Journal Stud 5(4):451–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700412331296392

Tyler I (2015) Classificatory struggles: class, culture and inequality in neoliberal times. Sociol Rev 63:493–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12296

Wessels B (2014) Exploring social change: process and context. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingsoke

Wetherell M (2009) Introduction: negotiating liveable lives-identity in contemporary Britain. In: Wetherell M (ed) Identity in the 21st Century: new trends in changing times. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 1–20

Winlow S, Hall S (2013) Rethinking social exclusion: the end of the social? Sage, London

Yesil B (2014) Press censorship in Turkey: Networks of state power, commercial pressures, and self-censorship. Communication, culture & critique 7:154–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/cccr.12049

Yesil B (2016) Media in new Turkey: the origins of an authoritarian neoliberal state. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Chicago and Springfield

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Şen, A.F. Invisibility of class identity in Turkish media: news coverage of class identity and class-based policies. Palgrave Commun 3, 32 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0037-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0037-9