Abstract

The transition of ICD has never been a straightforward initiative. As nations transition to ICD-11, ensuring its acceptance among the users is essential. To our knowledge, there are limited studies about the instrument and ICD-11 adoption. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to design an instrument and investigate the factors influencing the intention to use the ICD-11 among medical record officers (MROs) and assistant medical record officers (AMROs) at Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia facilities. Based on the current literature, a model based on the decomposed theory of planned behaviour (DTPB) was proposed. The model consisted of 13 dimensions and 12 hypotheses identified from previous studies. Using PLS-SEM, 185 survey data points were analysed. The study findings showed that ten factors have a significant impact on the suggested model. Users' subjective norm was the most influential factor in their intention to use ICD-11. Unexpectedly, perceived usefulness and was found to have no significant influence. This study is important for policymakers in strategising ICD-11 implementation efforts. This study's novelty lies in applying a DTPB theory model in the context of the intention to use ICD-11.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Healthcare institutions have an insatiable appetite for data and retain vast amounts of patient-level information in clinical records. However, only a small portion of these data can be used in day-to-day decision-making because of standardisation issues1. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) enables the alphanumeric coding of disease diagnoses and other health problems, which allows easier data storage, retrieval, and analysis2. ICD has served as the primary foundation for comparing statistics on causes of death and morbidity for more than a century3.

The 72nd World Health Assembly adopted the 11th revision of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-11) in 20194. Based on formal ontology, the ICD-11 is a distinct, adaptable, and effective health information system used in information technology (IT) infrastructures and with other classifications and terminologies5. Therefore, the use of ICD-11 introduces a transition from a largely manual workflow to work processes involving the electronic use of the ICD6. Essentially, users must learn to use the ICD-11 and adapt to new and fundamentally diverse methods of executing business processes in the healthcare setting.

There has been an increasing number of studies on the use of ICD-11. However, existing studies have focused mainly on training evaluation7 or from the perspective of clinicians8. To the best of our knowledge, limited studies have been performed on designing and applying an instrument for measuring intention to use the ICD-11. In the context of medical records personnel, which is this study's subject, studies on the topic are even more limited7. MROs and AMROs, also known as health information management professionals (HIMs) in developed countries, are tasked with enhancing the standards for clinical documentation to provide data and information for patient care9.

In developing countries such as Malaysia, MROs and AMROs are focused on nine specific areas ranging from disease and procedural codification, policies, and information management to quality assurance10. MROs and AMROs are essential in ensuring the quality of diagnosis documentation, ICD coding and, ultimately, the publication of the documented data at the national level. To bridge this gap, the current study focused on the scale validity of a model that incorporates variables influencing the intention to use the ICD-11 in the context of Malaysia, a developing nation. The PLS-SEM technique assessed the model and tested the structural hypotheses.

Literature review

The decomposed theory of planned behaviour (DTPB) has demonstrated that decomposing attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control increases the explanatory power of intentions to use technological innovations such as the ICD-115,11,12. First, the theory focused on compatibility, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness for users' attitudes, interpersonal influence, and external influence for the subjective norm and facilitating conditions and self-efficacy for perceived behavioural control. The theory then progresses from the three determinants of user behaviour (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control), which shape users' intentions11,13.

Intention to use the ICD-11 among MROs and AMROs

Pragmatically, ICD-11 implementation in Malaysia was still in an early stage at the time of data collection14. Thus, intention over actual usage is desirable, allowing investigation of MROs' and AMROs' acceptance at a time when more countries and health organisations were implementing the ICD-1115. In addition, implementing the ICD-11 at MOH facilities is a mandated effort involving all systems. In a mandatory environment, intentions are more suited than actual usage because they are measured concurrently with beliefs16,17. Users may hold an unfavourable opinion and not want to adopt the innovation16,18. Although they will eventually adopt the new coding system, they do so because there are no other options available and at the expense of the additional time and resources for the latest technology to be implemented successfully16,19.

Therefore, barriers to innovative technology such as the ICD-11 impact the intention and eventual usage of the ICD-1115. In the context of ICD transition, in previous studies, users faced significant challenges with minimal experience in the new and more complex coding system20,21, leading to inaccurate and unspecified coding22,23, which requires long and expensive training24. In ICD code selection, having too many options can be worse than having too few options, as this leads to increased inter- and intraobserver variability and improper use, especially if the system is time-consuming25,26.

Instrument needs

In general, researchers design instruments with sufficient relevant items and constructs. The goal is to capture the key constructs to predict the behaviour of interest. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a scale to model the factors influencing the intention to use the ICD-11 among MROs and AMROs at MOH facilities. Previous research has focused on developing and validating instruments on technology intentions or adoptions, which has led to the development of related theories. For example, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)27, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)28 and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)29. In various settings and contexts, these models have been modified and validated30,31,32.

The TPB is found to have a greater ability to predict and explain behaviours in a mandatory environment than the UTAUT and TAM16,33. However, the decomposed TPB (DTPB) model has superior predictive and explanatory power12. DTPB has been used extensively, involving innovations in the fields of education34, finance35 and healthcare11,36. Therefore, ICD-11, as a technological innovation in the context of this study5, we applied DTPB in a different setting, context and population involving MROs and AMROs in Malaysia.

Model and hypotheses

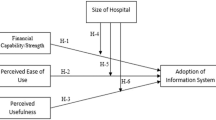

For this study, we outlined a model consisting of twelve hypotheses for the structural model. Figure 1 portrays the study's proposed model. The suggested model and scale refer to the intention to adopt the ICD-11 context at the Ministry of Health facilities involving MROs and AMROs.

Intention to use ICD-11

This study defines intention to use ICD-11 as the readiness of the users to act in using a newly introduced innovation37,38. Intention to use is hypothesised to be influenced by attitude (H1), subjective norm (H2), perceived behavioural control (H3) and previous ICD coding experience (H12)12. In the context of this study, the intention to use is explored from the point of view of the MROs and AMROs from the MOH facilities.

Attitude

In this study, the attitude was defined as MROs' and AMROs' tendency to accept or reject the use of the ICD-1139. It has been established that attitude is an essential predictor of a person's intention to use a newly introduced technology12,40. In the healthcare context, a positive attitude toward the new system improves the chances of the users' intention to adopt the system11. For example, in the use of electronic health records among doctors40. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: Attitudes towards ICD-11 positively influence MROs' and AMROs' intentions to use ICD-11.

Subjective norm

Subjective pressure from the social groups of MROs and AMROs influences the adoption intentions of ICD-11 codes. Social groups are usually people who are essential to respondents and consist of peers, colleagues, and supervisors in the workplace12,41. Previous studies have shown that the stronger the influence of these groups of people on the respondents, the greater the respondents' intention to perform the behaviour of interest42. In other words, reactions and feedback from people who are important to users will influence users' intention to use or not use the innovation. Mathai et al. reported that subjective norms positively influence intentions in the context of system use in healthcare11. As a result, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Subjective norm positively influence MROs' and AMROs' intentions to use ICD-11.

Perceived behavioural control

According to Ajzen, MROs' and AMROs' perceptions of the readiness of resources and materials to use an innovation such as the ICD-11 are defined as perceived behavioural control29. In line with DTPB12, users' perceived behavioural control should influence the intention to use ICD-11. A study by Gupta et al. reported that perceived behavioural control among individuals has a positive relationship with the usage intention of metaverse in healthcare43. Thus, this study hypothesises that MROs and AMROs are more likely to intend to use the ICD-11 when they feel they have more control over it.

H3: Perceived behavioural control positively influences MROs' and AMROs' intentions to use the ICD-11.

Previous ICD coding experience

Previous ICD coding experience is defined as prior use of ICD44,45. Past experiences play a significant role in determining intention towards a behaviour like using an innovation46. This is because experience allows new information to be more relatable to memory, thereby helping in the decision to use innovations47. In the context of ICD, previous experience has played a significant role in the acceptance of new classification systems, and it is hypothesised that48,49:

H12: Previous ICD coding experience positively influences MROs' and AMROs' intentions to use the ICD-11.

Decomposition of attitude

Perceived usefulness

According to the proposed model, attitudes toward the ICD-11 are determined by perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and compatibility. A system perceived to be useful by users will positively influence intention and, subsequently, the decision to use it. Hence, in this study's context, perceived usefulness is defined as the extent to which MROs and AMROs believe that the ICD-11 can improve their performance at work27. Studies have shown that users' perceived usefulness of a new technology influences their attitude toward the technology50. For example, in a study of users of healthcare-related systems such as the EHR, perceived usefulness was significantly related to users' attitudes11. With that in mind, we hypothesised the following:

H4: Perceived usefulness positively influences MROs' and AMROs' attitudes toward the ICD-11.

Perceived ease of use

In general, individuals can devote only a limited amount of effort to several tasks that involve purview51. Therefore, the extent to which MROs or AMROs believe that using the ICD-11 is effortless is defined as perceived ease of use. Previous studies have shown an empirical relationship between perceived ease of use and attitude52,53. Despite the adequacy of resources and support, difficulty levels of healthcare technology are essential in determining users' attitudes54. In line with DTPB and other studies, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: Perceived ease of use positively influences MROs' and AMROs' attitudes toward ICD-11.

Compatibility

The compatibility construct defines the extent to which the MROs and AMROs opine that the ICD-11 fulfils their experience, values, and current needs. As agents of change, policymakers at the MOH must be aware of how technological innovations such as the ICD-11 fill the gap compared to previous versions of classification. To accurately ascertain users' needs, policymakers must have good relationships with users55. Subsequently, the new system introduced will be compatible with the users, which leads to a positive attitude among them40. This significant relationship was observed when using big data in disaster management56. Consistent with these previous studies, we propose the following:

H6: Compatibility positively influences MROs' and AMROs' attitudes toward ICD-11.

Decomposition of subjective norm

Interpersonal influence

As the DTPB outlines, subjective norms are decomposed into interpersonal and external influences12. In the context of this study, the MROs and AMROs social group forms their interpersonal influence. Yeoh et al. found that social influence plays a significant role in behaviour57. Critical information, such as the use of the ICD-11, was shared among the users in this network. Previous studies have shown that interpersonal influence significantly influences users' subjective norms58. Therefore, the suggested hypothesis is as follows:

H7: Interpersonal influence positively influences MROs' and AMROs' subjective norms toward ICD-11.

External influence

Bhattacherjee defined external influence as influence from mass media, experts, and the government59. In this study's context, the external influence of ICD-11 use was not personal or unspecific to the MROs or AMROs. For any national-level implementation of systems introduced by the MOH, incentives provided by the government will be able to influence the subjective norm of the user60. Specifically, on the ICD-11 in Malaysia, the World Health Organization (WHO) actively engaged officers from the MOH. These findings subsequently led to efforts by the MOH to organise awareness sessions and prepare an e-learning platform to inform the MROs and AMROs of the advantages of the ICD-11. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8: External influence positively influences MROs' and AMROs subjective norms toward ICD-11.

Decomposition of perceived behavioural control

Self-efficacy

Perceived behavioural control is further decomposed into self-efficacy and facilitating conditions as defined in DTPB47. Under the framework of this research, self-efficacy is interpreted as MROs' and AMROs' confidence in using the ICD-11. If the respondents are confident, their choices, preparation, effort, mindset, and emotions will be geared toward the decision to use the ICD-1141. Previous studies focusing on the acceptance of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) among consumers and physicians have shown a positive significant relationship between self-efficacy and perceived behavioural control. If users are confident, they will opine that they have control over utilising a new system11. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H9: Self-efficacy positively influences MROs' and AMROs' perceived behavioural control toward ICD-11.

Facilitating conditions

Regarding DTPB, facilitating conditions are described as MROs' and AMROs' perceptions of the availability of resources to facilitate the use of the ICD-1147. In the use of the ICD-11, compared with the ICD-10, which is a manual process, the WHO has provided the ICD-11 Embedded Coding Tool (ICD-11 ECT) to assist in the search for suitable ICD-11 codes. The availability of this tool may affect users' perception of control in the use of ICD-116,61. Concerning the acceptance of healthcare technologies, Mathai et al. showed that the availability of facilitating conditions improves consumers' perceived behavioural control 62. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H10: Facilitating conditions positively influence MROs' and AMROs' perceived behavioural control of ICD-11.

ICD-11 training

Finally, the ICD-11 training is defined as the cognitive activities involving MROs, AMROs, and trainers that result in knowledge transfer63. In ICD, training plays a central role in ensuring standardisation and the quality of the coded data64. This is especially important during the transition periods between the two versions of the ICD8,26. Previous studies on the relationship between training and facilitating conditions in a hospital setting have shown a positive significant relationship36. Therefore, we hypothesised the following:

H11: ICD-11 training positively influences the facilitating conditions of MROs and AMROs in the use of ICD-11.

Method

A survey was conducted to collect data for this study using items adapted from previous studies65. The draft instrument was then translated and subjected to content validation before being disseminated for the pilot study66. The model was evaluated using PLS-SEM. Since the data distribution did not hinder the process, we assessed the research model for causality using a predictive technique.

Instrument establishment

The items and scales used in this study's questionnaire were adapted from previous studies (Table 2). The choice of items adapted from previous studies was based on permission from the publisher and whether they have been used in the general healthcare contexts or have undergone validation36,59,67,68,69,70. Given that the referred literature was in English, the questionnaire for this study was first prepared in English. In Malaysia, Malay is the official language, whereas English is widely spoken and often used with Malay language on an interchangeable basis71. To enhance respondents' comprehension of the questions, we drafted the questionnaire in two languages instead of one in each language.

Hence, forward and backward translations between English and Malay were performed. For forward translation, two translators translated the instrument from English to Malay. The researchers and translators then harmonised the differences between the two translations. Then, two other translators uninvolved in the study translated the instrument backwards from Malay to English. Most of the items were identical to the original English, and any differences were discussed and finalised.

The questionnaire is made up of five parts. They are the information sheet with the consent form, Section A—demographic-related items, Section B—items related to intention to use ICD-11, Section C—items related to attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, self-efficacy, facilitating conditions, compatibility, interpersonal influence and external influence, and Section D—ICD-11 training and previous ICD coding experience. Sections B, C and D are the scale questions. A 7-point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" or "extremely unimportant" to "strongly agree" or "extremely important", was used to assess respondents' intentions and factors influencing it. We adopted the items in this section from earlier studies and adapted them to suit the research context and subjects. There were four to seven items for each variable, with 71 items identified for the initial draft of the questionnaire36,69.

Five public health and health informatics experts agreed to evaluate the scale (71 items) for its clarity, relevance, simplicity, and ambiguity72. The content validity for each of the domains was assessed using the following indicators: (1) the content validity index (I-CVI); (2) the scale-level content validity index based on average methods (S-CI/AVE); (3) the scale-level content validity index based on the universal agreement method (S-CVI/UA); (4) the probability of change agreement (Pc); and; (5) the modified kappa (K) coefficient. We computed the CVI score with Microsoft Excel. After the expert panel's feedback, item FC6 was eliminated due to duplicity with FC3. It was also decided that some items were double-barrelled and subsequently restructured. Finally, the post-content validity instrument consisting of 78 items was verified.

Pilot study

The post-content validity instrument was piloted and involved 105 participants. The pilot study ensures the instrument's feasibility before data collection73. The reliability of the data collected in the pilot study was tested using SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All the domains were found to have Cronbach's alpha values of greater than 0.700. However, only 62 items with satisfactory factor loadings of more than 0.600 remained for the primary survey74.

Data collection and preparation

All MROs and AMROs employed by the Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOH) composed the study population (N = 479). We used the power analysis tool G*Power 3.1 to determine the ideal sample size for the survey75. The tool indicated that a minimum of 85 respondents is needed. Referring to Memon et al., the suggested sample size of 160–300 valid observations with careful consideration of the target population was made for Structural Equation Modelling (SEM)76. For example, for a total population of 400, a sample size of 200 is considered large. Additionally, as DTPB is a complex model, a sample with fewer than 100 is not advised for multivariate statistical analysis techniques like CB-SEM and PLS-SEM77.

Respondents were chosen using the simple random sampling method. Similar to previous studies78,79,80, the chosen method was justified due to the homogeneity of tasks related to ICD use between the MROs and AMROs and ensuring the representativeness of the medical records professionals10. A serialised list of MROs and AMROs was obtained from the MOH. The prospective respondents were identified using a random number generator. We collected more than the minimum sample size required (n = 185) from the data collection exercise, which took four months. Then, the respondents were invited via email to complete the questionnaire via the attached Google Form link. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents. Respondents who agreed to participate provided consent online (by checking the "I agree" box) before answering the survey. No information on respondents' identifiers was collected, and respondents did not need to log into their accounts to access the Google Form. The Research Ethics Committee, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2023-080) and the Medical Research & Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health (MOH) Malaysia (NMRR ID-23-00756-KIH (IIR) approved this study. The study was carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data analysis

Using Microsoft Excel spreadsheet worksheet, data were tabulated and compared, especially to aid in ascertaining the model's predictive relevance. Data processing for descriptive statistics was done with SPSS Statistics version 27.0. For data normality, we used the WebPower online calculator to perform the normality test81. All 185 responses were included in the analysis; most respondents were females (n = 143, 77.3%). The respondents had a mean duration of experience with ICD of 8.4 years.

The data were quantitatively analysed using the structural equation modelling (SEM) approach. SEM allows researchers to estimate and model complex interactions between several independent and dependent variables at the same time. We used the partial least square SEM (PLS-SEM) because the structural model estimation involves a more complex model involving many constructs. Two assessment phases are recommended for PLS-SEM procedures: measurement and structural. To elucidate the correlations between variables, the path coefficient (β), t-value, p-value, coefficient of determination (R2), and effect size (f2) were evaluated82.

Results

Data preparation and descriptive statistics

We used the WebPower online tool for data outlier identification and normality. Table 1 shows that no problems related to outliers were detected83,84. Skewness and kurtosis values were computed to determine univariate normality84. There was no missing data detected. The mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis of each construct are displayed in Table 1. The kurtosis and skewness scores ranged from -0.730 to 0.984. Therefore, the data were normally distributed. Every construct yielded satisfactory mean scores. The lowest mean was for attitude (M = 2.095), and the highest mean was for self-efficacy (M = 4.242).

Measurement model

We reported the validity and reliability of the model using the measurement model. The four phases of reflective measurement models are reflective indicator loadings, internal consistency reliability (ICR), convergent validity and discriminant validity85. Assessment of the reflective measurement model starts with examining the factor loadings. Factors with loadings higher than 0.500 were retained86. To compute the factor loadings of the items, we used SmartPLS 4.0.9.287. Two items with loadings of < 0.500 (INT7; 0.485 and SE5; 0.476) were removed. This deletion process aimed to maintain the validity and reliability of the model88. The loadings (60 items) are summarised in Table 2 and Fig. 2. Self-efficacy (SE4; 0.705) had the lowest factor loading, while perceived usefulness had the highest factor loading (PU5; 0.990).

Common method variance

Since the independent and dependent variables in this study were collected simultaneously from the same respondent, common method variance (CMV) may have been an issue91. We adopted the single-common-method-factor approach to account for CMV92. A method factor was created using the PLS marker variable approach93. First, we chose seven items from the Social Desirability Scale that were gathered from the same survey but were not part of the model and were evaluated: (1) "I like to gossip at time;" (2) "There have been occasions where I took advantage of someone else;" (3) "I'm always willing to admit it when I made a mistake;" (4) "I sometimes try to get even rather than forgive and forget;" (5) "At times I have really insisted on having things my own way;" (6) "I have never been irked when people expressed ideas very different from my own;" (7) "I have never deliberately said something that hurt someone's feelings94." These items served as marker variables. Then, using the marker variable as an exogenous variable, a method factor was created where each endogenous construct was predicted. Finally, upon comparison with the baseline model, significant paths remain significant in the method factor model. Therefore, we conclude that there was no CMV issue with the data.

Internal consistency reliability (ICR)

Using SmartPLS software, Rho_A, Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (CR) were computed for the ICR95. Higher values for Rho_A suggest higher reliability levels. Values higher than 0.700 are considered satisfactory86. Cronbach's alpha and the CR are two additional metrics for assessing the reliability of internal consistency. The values of Cronbach's alpha must be higher than 0.700. Table 2 shows the CR, Cronbach's alpha and Rho_A values. The Rho_A, Cronbach's alpha, and CR values of all the constructs are promising, indicating a stable ICR.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity is the degree to which a construct converges to represent the item variance. We used the average variance extraction (AVE) method to determine convergent validity. Each loading is squared with a minimum AVE of 0.500 (see Table 2). The "facilitating conditions" construct had the lowest AVE value (0.560). With an AVE of 0.971, the perceived usefulness construct achieves the maximum variance of (97.1%). The AVE values confirm the convergent validity of the model.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity is the degree to which a variable differs from other variables empirically. The heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio was employed to examine discriminant validity96. Table 3’s HTMT values are less than 0.900, and its confidence intervals do not include a value of 1. Thus, we have demonstrated the discriminant validity of the study.

Structural model

We evaluated the multivariate skewness and kurtosis recommended by Hair et al. and Cain et al. 97,98. The findings demonstrated that the data collected were not multivariate normal. Mardia's multivariate skewness was (β = 38.815, p < 0.05), and Mardia's multivariate kurtosis was (β = 242.305, p < 0.05). As a result, we used a 5000-sample resample bootstrapping approach, as recommended by Hair et al., to provide the path coefficients, standard errors, t-values, and p-values for the structural model99.

We assessed the structural model by bootstrapping the data involving 5000 subsamples, as summarised in Fig. 3. One hypothesis was deemed to be insignificant (H4). The other hypotheses (H1–H3, H5–H12) are significant at the 95% confidence interval, as shown in Table 4. Specifically, this study revealed that attitude (H1; β = 0.283; t = 4.102; p < 0.05), subjective norms (H2; β = 0.401; t = 4.664; p < 0.05), perceived behavioural control (H3; β = 0.160; t = 2.494; p = 0.006) and previous ICD coding experience (H12; β = 0.161; t = 2.506; p = 0.006) positively influence the intention to use ICD-11. On the predictors of attitude, we found that only perceived ease of use (H5; β = 0.155; t = 1.932; p = 0.027) and compatibility (H6; β = 0.368; t = 4.426; p < 0.05) positively affect attitude. On the other hand, perceived usefulness (H4; β = 0.037; t = 0.431; p = 0.333) does not significantly or positively influence attitude. For the predictors of subjective norm, this study showed that interpersonal influence (H7; β = 0.468; t = 5.820; p < 0.05) and external influence (H8; β = 0.174; t = 2.772; p = 0.003) positively affect the subjective norm of MROs and AMROs. Self-efficacy (H9; β = 0.150; t = 2.871; p = 0.002) and facilitating conditions (H10; β = 0.613; t = 8.832; p < 0.05) were linked to perceived behavioural control, and ICD-11 training (H11; β = 0.363; t = 5.504; p < 0.05) was linked to facilitating conditions.

For model fit evaluation, we used three indicators. They are the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and the exact fit criteria, d_ULS and d_G. The SRMR is the root mean square difference between the correlations that are observed and those implied by the model. Since SRMR is an absolute fit metric, zero denotes a perfect fit. A good fit is defined as a value less than 0.0897. The criteria d_ULS and d_G were additional reference points for fit evaluation. No cut-off values exist for the d_ULS or d_G indices100. Table 5 shows the acceptable model fit values of the index with 0.057 for SRMR, 6.396 for d_ULS and 3.609 for d_G.

Concerning the model's predictive relevance, the use of PLSpredict was proposed by Shmueli et al. 88. PLSpredict uses the holdout sample-based technique with a tenfold procedure to verify its predictive relevance and delivers case-level predictions on an item or construct level. According to Shmueli et al. 88, there is strong predictive power if all item differences (PLS-LM) are lower; if all are higher, predictive power is not confirmed; if the majority is lower, there is moderate predictive power; and if the minority is lower, there is low predictive power88. Table 6 shows that most of the PLS model errors were less than those of the LM model, indicating that the model proposed in this study has a moderate predictive ability.

Discussion

Several validity tests were performed to establish a valid and reliable model. From the literature, we adapted a total of 71 items. The instrument's content validity was assessed by five experts who scrutinised and scored the draft questionnaire. We then piloted the questionnaire among the study population and calculated the construct validity. As a result, eleven items were dropped, with 60 items used in the primary data collection.

Regarding internal consistency reliability, rho_A values between 0.700 and 0.950 are considered satisfactory. Higher values are undesirable as the items may be semantically redundant and may not be valid measures of the construct86. In the findings of our study, rho_A values for perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and previous ICD coding experience were found to exceed 0.950. However, we opine that the high-reliability issue raised by Hair et al. 97 may not be the case for this study for three reasons. Firstly, the constructs are based on a sound theoretical foundation. In addition, items of the constructs were reviewed by experts based on its relevance and specific items in the constructs were reverse-coded to ensure respondents' attentiveness.

This study also established a model based on the DTPB to investigate the factors that could affect MROs' and AMROs' adoption of the ICD-1112. Factors influencing the intention to use ICD-11 include attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control and previous ICD coding experience. Subjective norm was the strongest predictor of users' intention to use the ICD-11. Interpersonal and external factors significantly influence subjective norm, predicting the intention to use the ICD-11.

Determinants of intention to use ICD-11

Subjective norm, interpersonal and external influences

In line with DTPB, the study has shown that subjective norm positively influences the intention to use the ICD-1112. Ultimately, MROs' and AMROs' decisions to use the ICD-11 depend on the opinions of people who are important to them and believe they should use the ICD-11. Of the factors considered, subjective norm had the most significant impact on MROs' and AMROs' intentions to use the ICD-11 (H2). This finding is inconsistent with other studies that found that factors such as attitude are stronger predictors11,101,102. This study also showed that interpersonal influence is significantly related to users' subjective norms (H7). Given that MROs and AMROs consist of a group of closely knit civil servants with a niche area of expertise in the healthcare sector, it is logical that social group relations influence the MROs and AMROs' intentions to use the ICD-1110.

This study also showed that external factors significantly influenced the subjective norm (H8). Our findings align with those of other studies that have shown that government and external agencies significantly influence the subjective norms of users40,59. In the context of the mandatory use of a system such as the ICD-11, the MOH has a role in ensuring the uniform adoption of the ICD-11 across the board. Mandating a behaviour such as using the ICD-11 will lead to the eventual adoption of the ICD-11. However, MOH must still allocate sufficient resources to win the hearts and minds of users and ensure that they are motivated to use the ICD-11. This is because the observed use is mainly due to users not having the choice but to use ICD-11, which could negatively impact the data quality16.

Attitude, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and compatibility

Corresponding to DTPB12, attitude is another significant determinant influencing MROs' and AMROs' intention to utilise the ICD-11. Our study revealed that the users' favourable attitudes towards ICD-11 positively affect their intention (H1). Previous studies by Hsieh 40 and Mathai et al. 11 support the relationship between attitudes towards intentions to use newly introduced healthcare innovations. Moreover, our findings are also in accordance with the general attitudes among HIM professionals worldwide towards the ICD-11103,104.

Our study also confirmed that perceived ease of use (H5) and compatibility (H6) significantly influenced MROs' and AMROs' attitudes. If users perceive the ICD-11 as easy and fit well with their work, this will improve their tendency toward adopting the ICD-11. HIM professionals are known to operate in an increasingly complex and highly demanding environment105. A system that facilitates rather than adds to existing workloads is welcomed. Therefore, the MOH should actively engage the MROs and AMROs in system design and system use and in the subsequent implementation of suggestions to optimise the use of the ICD-11 at MOH facilities.

Contrary to the model and most related studies, we found that perceived usefulness is non-significant for attitude (H4)11,69. This means that the usefulness of the ICD-11 was not highly valued by respondents, indicating some ambivalence on its usefulness among MROs and AMROs. Moreover, Gajayanake et al. reported a complex relationship between how users perceive usefulness with attitude and their intention to use the innovation106. Nevertheless, at the time of data collection, the ICD-11 was still in the early phase of implementation, users were just being made aware of the new system, and most did not undergo formal training or use14. Future studies may investigate user perceptions after the ICD-11 was formally used at MOH facilities beginning in 2024.

Perceived behavioural control, facilitating conditions, self-efficacy and ICD-11 training

Consistent with the DTPB12, this study showed that perceived behavioural control influences the intention to use the ICD-11 (H3). In other words, when MROs and AMROs feel that the existing systems and themselves are ready, they will intend to use the ICD-11. This outcome corroborates the findings of Hung et al. involving the use of an online system among healthcare workers69. In Malaysia, the MOH organised engagement sessions with all stakeholders before using the ICD-11 to clarify doubts and queries among stakeholders107. In addition, the system with the ICD-11 ECT uses the same interface as the previous system to give users a sense of familiarity and control and improve the intention to use the ICD-11 among MROs and AMROs8,108.

The study also proved that facilitating conditions and self-efficacy significantly influenced perceived behavioural control. If the MROs and AMROs are confident and resources are available at arm's length, they will most likely have a sense of control when using the ICD-11. This result aligns with studies involving new systems or innovations in healthcare settings, such as the ICD-1169. In addition, we found that ICD-11 training significantly influenced the facilitating conditions of MROs and AMROs toward the ICD-11. This finding is consistent with that of Aggelidis et al. in the context of healthcare facilities109. Overall, these factors give users a sense of empowerment for continued use of the ICD-11.

Previous ICD coding experience

As proposed in the model, previous ICD coding experience significantly influenced the intention to use the ICD-11 (H12). That is, users with experience with the ICD-10 at MOH facilities were found to have favourable intentions to use the ICD-11. We opine that this could be due to the MOH's initiatives to identify the fears and uncertainty of MROs and AMROs. The MOH then took concrete steps to ensure the availability of learning materials110, coding guidelines111, engagement sessions107, and careful consideration to ensure minimal disruption of existing workflows112. Contrary to the findings of Alonso et al., in the context of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM/PCS, it was reported that experienced users felt that it was more challenging to shift to a new system in comparison to users with minimal to no experience. This is because of the higher coding specificity required from the documented information113.

Theoretical implications

The study is among the early studies examining factors influencing users' intention to use the ICD-11. Our work presents an empirically tested model for ICD-11 usage intention. The findings of our study significantly add to the body of knowledge already available on innovation intention-based models, particularly the intention to use ICD-11. First, we introduced an integrated innovation intention model based on DTPB. Two new variables—ICD-11 training and previous ICD coding experience have been incorporated into our suggested model.

Second, our proposed DTPB-based ICD-11 usage intention model offers a deeper comprehension of the users' psyche. Understanding human behaviour towards a newly introduced technology is valuable to the existing literature. The intention of users to adopt recently developed digital innovations can be measured and identified by our approach.

The final theoretical implication stems from the limitations of the current ICD-11 intention-based usage surveys. While previous research has documented the user experience, perceptions, and utilities, relatively few have investigated users' intentions to use ICD-11 and the factors influencing it 8,26,114. This limitation can be addressed by ensuring survey questions include information about factors affecting the intention to use ICD-11 among the users. Survey questions may cover topics such as perceptions towards ICD-11, social influences, and availability of resources. Our findings imply that users' subjective norm exhibits superior influence over all key constructs towards intention.

Practical implications

The findings from this study will be especially beneficial to the government healthcare providers and key policymakers. Firstly, our study revealed a strong relationship between subjective norms and intention, suggesting that regular communication involving all levels and agencies within the MOH is important. When the right information is spread among the users, those in the know will inform the other users and relay the intended information. For example, information like ICD-11's usefulness, ease of use, and compatibility with current workflow. In addition, we have also found that experienced users who had previously used ICD have a more positive intention to use ICD-11. Therefore, we suggest that policymakers tap on the so-called "old timers" in the industry to act as influencers and get the rest of the users' buy-ins upon the commencement of the ICD-11 implementation.

The implementation planners also must concurrently ensure the availability of coding experts and infrastructure consistent with Ibrahim et al. 8. Moreover, it is logistically impossible for experts to be available physically and for the infrastructure to be the same at all health facilities. The policymakers at the MOH must ensure the basic infrastructure to use ICD-11 is available and that the experts are available via social messaging applications to answer the related queries8,114. As a result, users will feel empowered and more confident to use ICD-11.

From this study, we found that ICD-11 training significantly influences the facilitating conditions for the users. Therefore, as best as possible, the policymakers can get the necessary resources and plan training sessions for all users before ICD-11 implementation. This is because users will likely resist using ICD-11 if they are unaware of using ICD-11 properly. Therefore, the training sessions can also serve as an opportunity to clarify any worry and anxiety among the users brought about by implementing this initiative.

Our study findings will also guide policymakers in shaping their implementation strategies in Malaysia, involving similar new systems in the future for the anticipated adoption of the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI)115,116,117. At the MOH facilities, procedural coding is also done by the MROs and AMROs. Not only that, the characteristics of the application used for ICHI are similar to ICD-11. Therefore, this study's results could assist in preparing the implementation of related classification or terminology systems in the country (Supplementary Information).

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. The first is the generalizability of the findings. This study only examined the perspective of MROs and AMROs from MOH in Malaysia. Depending on context and country, the process could involve other actors, such as physicians, administrative clerks, and policymakers, from codification to reporting results. Findings from studies conducted in multiple countries may provide more applicable and generalisable results. The respondents' recruiting technique may also have an impact on the results. The data were collected online. As a result, the sample may not accurately reflect the population of interest because it is a cohort of users accustomed to technology use. Future studies could extend these findings to examine changes in intentions postimplementation. In addition, the mixed methods methodology can incorporate rigorous qualitative data collection techniques to provide detailed information and improve the understanding of the factors impacting the intention to use the ICD-11.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study allows future studies to investigate better intentions to use the ICD-11 by utilising the instrument of this study. In addition, this study aimed to examine the essential factors influencing the intention to use the ICD-11 according to the DTPB. We also included previous ICD coding experience and ICD-11 training in the model. Both factors were found to be significant predictors of intention and facilitating conditions. The findings from this study may inform government policymakers from the users' perspective as health systems worldwide transition to ICD-11.

Data availability

The ethics approval guaranteed that the data would only be used for academic research purposes and that any sensitive or confidential information that could be used to identify or harm participants would be kept entirely confidential. Thus, the research data cannot be made public to preserve the participants' privacy. While this research is ongoing, the dataset is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Rosenbloom, S. T. et al. Data from clinical notes: A perspective on the tension between structure and flexible documentation. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 18, 181–186 (2011).

WHO. World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Who 2019, 5 (2021).

History of the development of the ICD. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/history-of-the-development-of-the-icd (2021).

World Health Organization. World Health Assembly Update, 25 May 2019. https://www.who.int/news/item/25-05-2019-world-health-assembly-update (2019).

Harrison, J. E., Weber, S., Jakob, R. & Chute, C. G. ICD-11: An international classification of diseases for the twenty-first century. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Making. 21, 1–10 (2021).

World Health Organization. ICD-11 Reference Guide. https://icd.who.int/icd11refguide/en/index.html#2.01.00Part2ICDmaintenanceandapplication%7Cpart-2-using-icd11%7Cc2.

Eastwood, C. A. et al. Training and experience of coding with the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision. Health Inform. Manag. J. 52, 92–100 (2021).

Ibrahim, I. et al. ICD-11 Morbidity Pilot in Kuwait: Methodology and lessons learned for future implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 3057 (2022).

IFHIMA. Examining Today's HIM Workforce with Recommendations for Elevating the Profession. (2022).

Ministry of Health, M. Garis Panduan Pembangunan Dan Perkembangan Kerjaya Profesion Pegawai Dan Penolong Pegawai Tadbir (Rekod Perubatan).

Mathai, N., McGill, T. & Toohey, D. Factors influencing consumer adoption of electronic health records. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 62, 267–277 (2020).

Taylor, S. & Todd, P. A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inform. Syst. Res. 6, 144–176 (1995).

Ali, S., Usama Javed, H. M., Ali, W. & Zahid, H. Decoding men’s behavioral responses toward green cosmetics: An investigation based on the belief decomposition approach. J. Environ. Planning Manag. 66, 2640–2667 (2023).

Ooi, E. C. W. et al. Planning for ICD-11 Transition in Malaysia. in WHO-Family of International Classifications Network Annual Meeting 2023 (Bonn, Germany, 2023).

Conner, M. & Norman, P. Understanding the intention-behavior gap: The role of intention strength. Front. Psychol. 13, 923464 (2022).

Hwang, Y., Al-Arabiat, M. & Shin, D. H. Understanding technology acceptance in a mandatory environment: A literature review. Inform. Develop. 32, 1266–1283 (2016).

Jeyaraj, A., Dwivedi, Y. K. & Venkatesh, V. Intention in information systems adoption and use: Current state and research directions. Int. J. Inf. Manage 73, 102680 (2023).

Heidenreich, S. & Talke, K. Consequences of mandated usage of innovations in organisations: Developing an innovation decision model of symbolic and forced adoption. AMS Rev. 10, 279–298 (2020).

Alyahya, M. S. & Khader, Y. S. Health care professionals’ knowledge and awareness of the ICD-10 coding system for assigning the cause of perinatal deaths in Jordanian hospitals. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 12, 149–157 (2019).

Lowe, J. R., Raugi, G., Reiber, G. E., Whitney, J. A. D. & Pra, A. M. A. Changes in classifications of chronic lower-limb wound codes in patients with diabetes: ICD-9-CM versus ICD-10-CM. Adv. Skin Wound Care 28, 84–92 (2015).

Lin, H. L., Cheng, S. M., Hsu, D. F., Huang, C. C. & Wu, D. C. Information system implementation optimizes medical coding. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 264, 1706–1707 (2019).

Amarouche, I. A., Ahmed Zaid, D. & Kenaza, T. Implementation of a Medical Coding Support System by Combining Approaches: NLP and Machine Learning. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 11470 LNCS, 133–147 (2019).

Hellman, J. B., Lim, M. C., Leung, K. Y., Blount, C. M. & Yiu, G. The impact of conversion to International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) on an academic ophthalmology practice. Clin. Ophthalmol. 12, 949–956 (2018).

Khair, S. et al. Paving the Way: A Cost and Outcome Evaluation Framework for the Transition from the 10th to the 11th Version of the International Classification of Disease|Perspectives. Perspect Health Inf Manag 1–14 (2020).

Jones, P., Hughes, T. & Morton, T. Information technology coding systems in the emergency department: It is not the tools, it is how we use them. Emerg. Med. Aust. 31, 700–701 (2019).

Golpira, R. et al. Evaluation of the implementation of International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision for morbidity coding: Rationale and study protocol. Inform. Med. Unlocked 25, 100668 (2021).

Davis & Fred D. Technology acceptance model: TAM. Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption 205–219 (1989).

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B. & Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q 27, 425–478 (2003).

Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. Action Control 11–39 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2.

Klaic, M. et al. Application of the extended technology acceptance model to explore clinician likelihood to use robotics in rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2022.2060356 (2024).

Shaikh, I. M. & Amin, H. Consumers’ innovativeness and acceptance towards use of financial technology in Pakistan: Extension of the UTAUT model. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 52, 114–122 (2023).

Wong, G. Z., Wong, K. H., Lau, T. C., Lee, J. H. & Kok, Y. H. Study of intention to use renewable energy technology in Malaysia using TAM and TPB. Renew. Energy 221, 119787 (2024).

FakhrHosseini, S. et al. User adoption of intelligent environments: A review of technology adoption models, challenges, and prospects. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 40, 986–998 (2024).

Liao, M. M. M. & Liao, M. M. M. A study on the acceptance and influencing factors of online teaching in China-Taking mosoteach cloud class as an example. Proceedings - 2020 International Conference on Computers, Information Processing and Advanced Education, CIPAE 2020 164–169 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/CIPAE51077.2020.00051.

Abdullahi, A. & Othman, A. H. A. Financial inclusion enhancement through the adoption of Islamic microfinance in Nigeria. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 37, 486–505 (2021).

Chang, M. Y., Kuo, F. L., Lin, T. R., Li, C. C. & Lee, T. Y. The intention and influence factors of nurses’ participation in telenursing. Informatics. 8, 35 (2021).

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behaviour—The Reasoned Action Approach. (2010).

Almagrashi, A., Mujalli, A., Khan, T. & Attia, O. Factors determining internal auditors’ behavioral intention to use computer-assisted auditing techniques: An extension of the UTAUT model and an empirical study. Future Business J. 9, 1–19 (2023).

Ajzen, I. & Crano, W. Attitides and Attitude Change. Taylor & Francis Group (2008).

Hsieh, P. J. Physicians’ acceptance of electronic medical records exchange: An extension of the decomposed TPB model with institutional trust and perceived risk. Int. J. Med. Inform. 84, 1–14 (2015).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 50, 179–211 (1991).

Jia, Q., Xu, X., Zhou, M., Liu, H. & Chang, F. Exploring the determinants of continuous intention in TikTok from the perspective of social influence: A mixed approach of SEM and fsQCA. J. Electron. Business Digital Econ. 2, 45–68 (2023).

Jee Gupta, O. et al. Understanding the intention to use metaverse in healthcare utilising a mix method approach. Article Int. J. Healthcare Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/20479700.2023.2183579 (2023).

Alshammari, M. H. & Alenezi, A. Nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction: the role of technology integration, self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience. BMC Nurs 22, 1–15 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. The acceptance and use of digital technologies for self-reporting medication safety events after care transitions to home in patients with cancer: Survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e47685 (2024).

Alharbi, S. & Drew, S. Using the technology acceptance model in understanding academics' behavioural intention to use learning management systems. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 5, (2014).

Taylor, S. & Todd, P. venkates. MIS Q 19, 561–568 (1995).

Hazlewood, A. ICD-9 CM to ICD-10 CM: Implementation Issues and Challenges. (2003).

Sand, J. N. J. N. & Elison-Bowers, P. ICD-10-CM/PCS: Transferring Knowledge from ICD-9-CM. Perspectives in Health Information Management / AHIMA, American Health Information Management Association 10, (2013).

Li, J., Liu, G., Chen, Y. & Li, R. Study on the influence mechanism of adoption of smart agriculture technology behavior. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–11 (2023).

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P. & Warshaw, P. R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manage Sci. 35, 982–1003 (1989).

Shaygan, M. & Jaberi, A. The effect of a smartphone-based pain management application on pain intensity and quality of life in adolescents with chronic pain. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12 (2021).

Foglia, E. et al. The role of INTERCheckWEB digital innovation in supporting polytherapy management. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–13 (2023).

Chan, K. G., Pawi, S., Ong, M. F., Kowitlawakul, Y. & Goy, S. C. Simulated electronic health documentation: A cross-sectional exploration of factors influencing nursing students’ intention to use. Nurse Educ. Pract. 48, 102864 (2020).

Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of Innovations: Modifications of a Model for Telecommunications. Die Diffusion von Innovationen in der Telekommunikation 25–38 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-79868-9_2.

Zaman, U., Zahid, H., Habibullah, M. S. & Din, B. H. Adoption of Big Data Analytics (BDA) Technologies in Disaster Management: A Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior (DTPB) Approach. Cogent Business Manag. 8, (2021).

Yeoh, R. et al. What determines intentions to use mobile fitness apps? The independent and joint influence of social norms. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 40, 121–130 (2024).

Do, T. H., Nguyen, H. P. T. & Dang, T. H. Factors Influencing the Intention of Using Solar Energy Household Appliances with an Extended TPB Model Approach: Evidence from Vietnam. Contemporary Economic Issues in Asian Countries: Proceeding of CEIAC 2022, Volume 1 25–44 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9669-6_2.

Bhattacherjee, A. Acceptance of E-commerce services: The case of electronic brokerages. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Humans. 30, 337–344 (2000).

Xu, J., Pan, Y. & Li, Q. Influencing factors of health screening among retirees: An extended TPB approach. Front. Public Health 12, 1320920 (2024).

Yuen, K. F., Huyen, D. T. K., Wang, X. & Qi, G. Factors influencing the adoption of shared autonomous vehicles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17, 4868 (2020).

Mathai, N., McGill, T. & Toohey, D. Factors influencing consumer adoption of electronic health records. J. Comput. Inform. Syst. 62, 267–277 (2022).

Gallivan, M. J., Spitler, V. K. & Koufaris, M. Does information technology training really matter? A social information processing analysis of coworkers’ influence on IT usage in the workplace. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 22, 153–192 (2005).

Eastwood, C. A., Khair, S. & Southern, D. A. Decision algorithm for when to use the ICD-11 3-part model for healthcare harms. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 1–7 (2021).

Story, D. A. & Tait, A. R. Survey research. Anesthesiology 130, 192–202 (2019).

Almanasreh, E., Moles, R. & Chen, T. F. Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Res. Social Administr. Pharmacy 15, 214–221 (2019).

Chau, P. Y. K. & Hu, P. J. H. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A model comparison approach. Decis. Sci. 32, 699–719 (2001).

Taylor, S. & Todd, P. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Res. Marketing 12, 137–155 (1995).

Hung, S. Y., Ku, Y. C. & Chien, J. C. Understanding physicians’ acceptance of the Medline system for practicing evidence-based medicine: A decomposed TPB model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 81, 130–142 (2012).

Zaman, N., Goldberg, D. M., Kelly, S., Russell, R. S. & Drye, S. L. The relationship between nurses’ training and perceptions of electronic documentation systems. Nurs. Rep. 11, 12–27 (2021).

Kong, Y. C. et al. Development and validation of a dual-language (English and Malay) needs assessment tool for breast cancer (NeAT-BC). Diagnostics. 13, 241 (2023).

Yaghmaie, F. Content validity and its estimation. J. Med. Educ. 1, 8–8 (2003).

Bowden, A., Fox-Rushby, J. A., Nyandieka, L. & Wanjau, J. Methods for pre-testing and piloting survey questions: Illustrations from the KENQOL survey of health-related quality of life. Health Policy Plan 17, 322–330 (2002).

Hair Joseph F., Black William C., Babin Barry J. & Anderson Rolph E. Multivariate Data Analysis. (Pearson, 2013).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Memon, M. A. et al. Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations. J. Appl. Struct. Equation Model. (2020).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (The Guilford Press, 2016).

Wolelaw, G. A., Yalew, W. A., Azene, A. G. & Wassie, G. T. Rabies prevention practices and associated factors among household heads in Bure Zuria district, North West Ethiopia. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–10 (2022).

Taherkhani, Z., Kaveh, M. H., Mani, A., Ghahremani, L. & Khademi, K. The effect of positive thinking on resilience and life satisfaction of older adults: A randomised controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–9 (2023).

Niriayo, Y. L., Asgedom, S. W., Demoz, G. T. & Gidey, K. Treatment optimisation of beta-blockers in chronic heart failure therapy. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–8 (2020).

WebPower Statistical power analysis online. https://webpower.psychstat.org/models/kurtosis/ (2018).

Hair, J. F. et al. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. 1–29 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_1.

Mishra, P. et al. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card Anaesth. 22, 67 (2019).

Seijas-Macias, A., Oliveira, A. & Oliveira, T. A. The skewness and kurtosis of the product of two normally distributed random variables. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 52, 80–93 (2023).

Basco, R., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. Advancing family business research through modeling nonlinear relationships: Comparing PLS-SEM and multiple regression. J. Family Business Strategy 13, 100457 (2022).

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Business Rev. 31, 2–24 (2019).

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S. & Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmBH (2022).

Shmueli, G. et al. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 53, 2322–2347 (2019).

Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13, 319–339 (1989).

Lee, Y. H., Hsieh, Y. C. & Chen, Y. H. An investigation of employees’ use of e-learning systems: Applying the technology acceptance model. Behav. Inform. Technol. 32, 173–189 (2013).

Avolio, B. J., Yammarino, F. J. & Bass, B. M. Identifying common methods variance with data collected from a single source: An unresolved sticky issue. 17, 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700303 (1991)

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Rönkkö, M. & Ylitalo, J. PLS marker variable approach to diagnosing and controlling for method variance. ICIS 2011 Proceedings (2011).

Fischer, D. G. & Fick, C. Measuring social desirability: short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316449305300201153, 417–424 (1993)

Aanondsen, C. M., Jozefiak, T., Heiling, K., Lydersen, S. & Rimehaug, T. Psychometric properties of the Inventory of Life Quality in children and adolescents in Norwegian Sign Language. BMC Psychol. 9, 1–14 (2021).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135 (2015).

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. & Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)—Joseph F. Hair, Jr., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian Ringle, Marko Sarstedt. Sage (2017).

Cain, M. K., Zhang, Z. & Yuan, K. H. Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation. Behav. Res. Methods 49, 1716–1735 (2017).

Ramayah, T., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H. & Memon, M. A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated Guide and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis (2nd Ed.). (Pearson, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018).

Habibi, A., Sofyan, S. & Mukminin, A. Factors affecting digital technology access in vocational education. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–12 (2023).

Hsieh, H. L., Kuo, Y. M., Wang, S. R., Chuang, B. K. & Tsai, C. H. A study of personal health record user’s behavioral model based on the PMT and UTAUT integrative perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 14, 8 (2016).

Jian, W. S. et al. Factors influencing consumer adoption of USB-based Personal Health Records in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12, 1–8 (2012).

iFHIMA Endorses the Implementation of ICD-11—IFHIMA. https://ifhima.org/ifhima-endorses-the-implementation-of-icd-11/.

International Federation of Health Information Management Associations. IFHIMA Fosters Planning for ICD-11 Adoption with Global Case Studies. (2021).

Fenton, S. H., Low, S., Abrams, K. J. & Butler-Henderson, K. health information management: Changing with time. Yearb Med. Inform. 26, 72–77 (2017).

Gajanayake, R., Sahama, T. & Iannella, R. The role of perceived usefulness and attitude on electronic health record acceptance. 2013 IEEE 15th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services, Healthcom 2013 388–393 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/HEALTHCOM.2013.6720706.

Ahmad SAH et al. ICD-11 Awareness and Training Among MOH Personnel. in WHO-Family of International Classifications Network Annual Meeting 2023 (Bonn, Germany, 2023).

Ooi, E. C. W. et al. MyHDW and HMIS ICD-11 Systems' Transition. in WHO-Family of International Classifications Network Annual Meeting 2023 (Bonn, Germany, 2023).

Aggelidis, V. P. & Chatzoglou, P. D. Using a modified technology acceptance model in hospitals. Int. J. Med. Inform. 78, 115–126 (2009).

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Moodle Pusat Informatik Kesihatan. http://www.pik_lms.moh.gov.my/moodle/.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Manual Rujukan Pengekodan ICD-11. (Ministry of Health Malaysia, Putrajaya, 2023).

Azman A et al. Impact of ICD-11 on Workflow at MOH, Malaysia Hospitals. in WHO-Family of International Classifications Network Annual Meeting 2023 (Bonn, Germany, 2023).

Alonso, V. et al. Problems and barriers in the transition to ICD-10-CM/PCS: A qualitative study of medical coders’ perceptions. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 932, 72–82 (2019).

Zhang, M. et al. Methodologies and key considerations for implementing the International Classification of Diseases-11th revision morbidity coding: Insights from a national pilot study in China. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1093/JAMIA/OCAE031 (2024).

Wübbeler, M. et al. Coding public health interventions for health technology assessments: A pilot experience with WHO’s International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI). Front. Public Health 9, 620637 (2021).

Fortune, N., Madden, R. & Almborg, A. H. Use of a new international classification of health interventions for capturing information on health interventions relevant to people with disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 15, 145 (2018).

Fortune, N., Madden, R., Riley, T. & Short, S. The International Classification of Health Interventions: An “epistemic hub” for use in public health. Health Promot. Int. 36, 1753–1764 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this document.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.C.W.O. drafted the manuscript, contributed to analysis tools or data, and conducted statistical analyses. Z.M.I. reviewed the final manuscript and provided research ideas and guidance, M.R.A.M. reviewed the final manuscript and provided research ideas and guidance, A.S.A.F. reviewed the final manuscript and contributed to the data analysis, A.A. reviewed the final manuscript and contributed in data collection, M.N.M. reviewed the final manuscript and contributed in the methodology, N.M.M. reviewed the final manuscript and provided research ideas.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ooi, E.C.W., Isa, Z.M., Manaf, M.R.A. et al. Factors influencing the intention to use the ICD-11 among medical record officers (MROs) and assistant medical record officers (AMROs) in Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Sci Rep 14, 9926 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60439-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60439-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.