Abstract

The timing of the initial peopling of the Americas is unresolved. Because the archaeological record necessitates discussion of human entry from Beringia into southern North America during the last glaciation, addressing this problem routinely involves evaluating environmental parameters then targeting areas suitable for human settlement. Vertebrate remains indicate landscape quality and are a key dataset for assessing coastal migration theories and the viability of coastal routes. Here, radiocarbon dates on vertebrate specimens and archaeological sites are calibrated to document species occurrences and the ages of human settlements across the western expansion and decay of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet (CIS) during the Late Wisconsin Fraser Glaciation in four subregions of the north Pacific coast of North America. The results show archaeological sites occur after glacial maxima and are generally consistent with the age of other securely dated earliest sites in southern North America. They also highlight gaps in the vertebrate chronologies around CIS maxima in each of the subregions that point to species redistributions and extirpations and signal times of low potential for human settlement and subsistence in a key portion of the proposed coastal migration route. This study, therefore, defines new age constraints for human coastal migration theories in the peopling of the Americas debate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The peopling of the Americas is an enduring focus of archaeological scholarship and debate1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. The timing of initial human arrivals and the routes people followed from Beringia are not yet fully resolved. Earliest securely dated archaeological sites indicate humans were in or had migrated through southern North America by 14.5 ka to 15.539,40,41,42 and around 16 ka ago43,44. These sites postdate the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)45 when the Cordilleran Ice Sheet (CIS) and the Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) coalesced, blocking mid-continental terrestrial passage south. Current research indicates that a corridor between the decaying ice sheets may have been open from as early about 16 ka–15.5 ka46 or 14.9 ka ago47,48, although it may not have been fully open before 13.8 ± 0.5 ka46 and able to support human life until 13.5–13 ka49,50 or as late as 12.7 ka ago51. Thus, it is not yet clear if human groups entering North America some 16–14.5 ka ago would have been able to do so via a mid-continental route through an emergent ice-free corridor34. An alternative hypothesis suggests these early groups migrated on a north Pacific coast route that was already substantially open for human passage in front of the western margin of the CIS4,11,15,30,34,35,37,52,53.

The recent discovery of human footprints in the Lake Otero playa at White Sands National Park, New Mexico is significant in the peopling of the Americas debate. The footprint trackways have been estimated to be 23 ka and 21 ka old based on radiocarbon dates on propagules of the grass-like perennial herb, Ruppia cirrhosa, embedded in layers of sediment between the footprints54. Controversy about these dates focuses on the possibility of a radiocarbon reservoir in the water in which the dated seeds grew and the sedimentary context of the trackways55,56,57,58,59,60,61. To address the dating, three new radiocarbon ages on bulk terrestrial pollens from the same sediment layers as those of the Ruppia seeds and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) ages on the sediments from the human footprint–bearing sediment sequence were analysed62. The pollen ages span 25.9–20.3 ka ago and include large uncertainties ranging from 2.3 ka to 2.5 ka54 characterised the sediments from which the pollen was sampled as alluvial and aeolian. Such sediments consist of redeposited materials and may include ancient pollen that had been eroded and transported from older deposits in the lake basin. Because of this the new pollen dates should be considered maximum ages. Technical descriptions of dated pollens and of the sediments from which they were sampled were not provided and could assist in clarifying the sedimentary context of the radiocarbon dated pollen. The bulk aliquot OSL samples were collected from dark gray clays that are a lithological unit separate from and underlying the deposits that contain the trackways62. The Law of Superposition predicts that the trackways must be younger, by some unknown amount, than the 16.2–23.3 ka ages from the OSL results. Therefore, the new dates may generally correspond with the initial seed ages and represent progress in the study of the formation history of the trackways, but do not fully resolve the controversy. Although additional work is needed to assess the age of the White Sands footprints, the potentially early age of the site raises new questions about initial human migrations during the middle of the LGM, when the CIS and LIS restricted human passage southward. The implication being that either humans entered southern North America by land before the ice sheets merged, or they did so along the north Pacific coast at an earlier date than has yet been considered in detail.

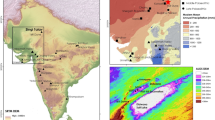

During the Late Wisconsin Fraser Glaciation on the north Pacific coast, the CIS would have obstructed human settlement and limited subsistence resources where vertebrates declined or were absent due to climate extremes. Although the occurrence and quality of unglaciated areas available for humans has been a central consideration in coastal migration theory since inception4, the ecological viability of a coastal route has not been fully evaluated across the western expansion and retreat of the CIS. To address this, the current study assembles radiocarbon dates on vertebrate specimens and archaeological sites from across the north Pacific coast (Fig. 1) and uses current statistical methods to calibrate and model age estimates into chronologies. This approach aims to identify evidence of settings viable for vertebrate and human populations across the growth and decay of CIS. Four subregions of the north Pacific coast are considered: Southeast Alaska, Haida Gwaii, the central coast including north Vancouver Island, and a south coast subregion including southern Vancouver Island and coastal northwest Washington. Each subregion has a specific glaciation history within the broader record63 and history of archaeological and paleontological research. The timespan of interest is from 30 ka ago at the transition to the Late Wisconsin as climate changed from interstadial to full glacial through the beginning of the present interglaciation to about 10 ka ago. Results evidence when and where human groups could have been sustained with implications for human coastal migration theory.

The north Pacific coast showing numbered locations from which radiocarbon dates were included in this study: 1 Manis, 2 Ayer, 3 Glenrose Cannery, 4 Stave Watershed, 5 Courtney, 6 Quadra Island, 7 Port Eliza Cave, 8 P2, Arch-2, Resonance and Sparkle caves and Kokish River, 9 Bear Cove, 10 Namu and Calvert, Triquet and Hunter islands, 11 Kilgii Gwaii, 12 Gaadu Din caves, 13 Richardson Island, 14 K1 Cave, 15 White Creek, 16 Chuck Lake, 17 Alexander Archipelago, 18 Hidden Falls, 19 Ground Hog Bay. Location descriptions are a supplementary file. Subregions: Southeast Alaska—gold, Haida Gwaii—rose, central coast—violet, south coast—blue. (Created in Inkscape 1.2.1. https://inkscape.org).

Results

To find evidence of terrain able to support humans across the expansion and decay of the CIS during Late Wisconsin Fraser Glaciation on the north Pacific coast of North America, I constructed four chronologies based on 233 radiocarbon dates from archaeological sites and vertebrate specimens. Table S1 lists each date and its source reference. The ages of archaeological sites are direct evidence of a human presence. Those of vertebrates are proxy records that indicate environments able to provision human populations. Radiocarbon dates were calibrated in OxCal 4.4.464 with IntCal2065 and Marine2066 data.

From Southeast Alaska, 74 radiocarbon dates on bones from 15 caves and three archaeological sites in the Alexander Archipelago were recalibrated and produced a well-constrained chronology (Fig. 2, Fig. S1; Tables S1 and S2). A decline in the number of dates between 20–13 ka ago and a hiatus from at least 17.7–18.82 ka calBP indicates that vertebrates declined in abundance and may have been absent for some 1,120 years due to climate intolerance during the ice maximum. Archaeological sites in Southeast Alaska postdate that maximum and span from 12.08 ka calBP (12.46–11.83 ka calBP, 95.4%).

Southeast Alaska chronology. Bayesian model of 74 calibrated AMS 14C ages on vertebrates from 15 caves and on bone and charcoal from three archaeological sites in Alexander Archipelago. Each curve indicates a single sample distribution. Calibration and Bayesian modeling are based on OxCal v 4.4.464. The white vertical band indicates the CIS ice maximum and unlikely human settlement.

The radiocarbon chronology for Haida Gwaii consists of 66 radiocarbon dates on bone and charcoal from six localities (Fig. 3, Fig. S2; Tables S1 and S3). The vertebrate record preceding the Late Wisconsin glacial ice maximum is limited to one date on caribou antler of 45.67 ka calBP (46.99–44.6 ka calBP, 95.4%; not shown in Fig. 3). Remaining radiocarbon dates span the latest Pleistocene and early Holocene. A radiocarbon age estimate of 17.31 ka calBP (17.54–17.06 ka calBP, 95.4%) on a bear bone is the earliest date following the ice maximum. Environmental conditions attracted this large terrestrial mammal. A gap of about 3.8 ka until 13.15 ka calBP (13.31–13.08 ka calBP, 95.4%) suggests bears may have recolonized Haida Gwaii near the onset of the Younger Dryas cold event and then persisted. Earliest archaeological evidence dates to 13.54 ka calBP (13.6–13.46 ka calBP, 95.4%) and continues across several sites into the Holocene.

Haida Gwaii chronology. Bayesian model of 66 calibrated AMS 14C ages on vertebrates and on bone and charcoal from archaeological sites on Haida Gwaii. Each curve indicates a single sample distribution. Calibration and Bayesian modeling are based on OxCal v 4.4.464. The white vertical band indicates the CIS ice maximum and unlikely human settlement.

The central cost radiocarbon chronology consists of 46 radiocarbon dates on vertebrates and archaeological materials (Fig. 4, Fig. S3; Tables S1 and S4). The vertebrate record directly preceding the glacial ice maximum comprises a diverse cool temperate fauna from 21.93 ka calBP (22.19–21.46 ka calBP, 95.4%) to 19.66 ka calBP (20.10–19.19 ka calBP, 95.4%). At Port Eliza Cave67, a 4.3 ka hiatus in the vertebrate record and a sedimentary deposit indicative of glacial ice cover to 14.36 ka calBP (14.83–14.1 ka calBP, 95.4%) give way to overlying diamict and the return of cool temperate adapted mountain goat and deer mouse. On northeast Vancouver Island, brown bear from 14.58 ka calBP (14.91–14.31 ka calBP, 95.4%) and black bear from 13.8 ka calBP (14.02–13.61 ka calBP, 95.4%) are early colonizers, as is deer mouse at 13.86 ka calBP (14.03–13.62 ka calBP, 95.4%). Archaeological sites span from 13.92 ka calBP (14.81–13.49 ka calBP, 95.4%) and 13.31 ka calBP (13.42–13.24 ka calBP, 95.4%) in the central coast subregion north of Vancouver Island.

Central coast chronology. Bayesian model of 46 calibrated AMS 14C ages on vertebrates and on bone and charcoal from archaeological sites in the central coast subregion of the north Pacific coast. Each curve indicates a single sample distribution. Calibration and Bayesian modeling are based on OxCal v 4.4.464. The white vertical band indicates the CIS maximum in the Queen Charlotte Sound and north Vancouver Island, and the light grey vertical band indicates ice maximum at north Vancouver Island (see manuscript text).

The radiocarbon chronology for the south coast subregion consists of 47 radiocarbon dates on vertebrates and includes several archaeological sites (Fig. 5, Fig. S4; Table S1 and S5). An age estimate of 20.54 ka calBP (21.15–19.9 ka calBP, 95.4%) on a mammoth bone is the terminal date preceding Late Wisconsin Fraser glacial ice cover on south Vancouver Island. Stellar sea lion is an early colonizer on southeastern Vancouver Island from 13.66 ka calBP (13.955–13.418 ka calBP, 95.4%). Two Pleistocene megafauna species, mastodon and bison, were found with earliest archaeological records at 13.92 ka calBP (14.02–13.79 ka calBP, 95.4%) from Manis68,69 (mastodon) and 13.91 ka calBP (14.02–13.79 ka calBP. 95.4%) from Ayer70 (bison). Clovis, a distinctive and widespread early North American archaeological culture significant in the peopling of the Americas scholarship, is included as a reference point for the discussion. Clovis age parameters are based on radiocarbon dated sites primarily in the American Southwest and Great Plains17 where this culture spans approximately 13.59–12.74 ka calBP (Table S1 and S5).

South coast chronology. Bayesian model of 47 calibrated AMS 14C ages on bones of vertebrates and on bone and charcoal from archaeological sites in the south coast subregion of the north Pacific coast. Each curve indicates a single sample distribution. Clovis age ranges from19 are included as a reference (see text). Calibration and Bayesian modeling are based on OxCal v 4.4.464. The white vertical band indicates the CIS ice maximum and unlikely human settlement.

Discussion

Occurrences of vertebrates and archaeological sites across the western expansion and retreat of the CIS during the Late Wisconsin Fraser Glaciation define age constraints for human migrations on the north Pacific coast of North America. The CIS had started to develop by 30 ka ago (30–25 ka 14C BP)63. At its maximum extent ice covered nearly all of British Columbia, southern and central Yukon, and parts of Alaska, Alberta, Washington, Idaho, and Montana47,48. It advanced west toward the edge of the British Columbia continental shelf 19.3–20.5 ka ago (16–17 14C BP) and reached maximum southern extent 18.3–17 ka calBP years ago (15–14 ka 14C BP), then decayed rapidly due both to climate warming and calving at the western margin of the ice sheet and persisted until 12.9–12.5 ka ago (11.0–10.5 ka 14C BP)71. The CIS growth and decay and the geometry of its western margin varied across the Pacific coast. Differences in CIS loading and unloading resulted in varied local isostatic responses and sea-level curves71,72.

As the CIS expanded west and south, terrain was overrun, and faunal communities were redistributed. Diverse biota of plants and animals persisted beyond glacial ice margins to the north in Alaska and the Yukon, to the south in the northwestern United States, and possibly also in isolated coastal refugia73,74.

Each of the four north Pacific coast radiocarbon chronologies includes a hiatus when no vertebrates occur and that generally corresponds with the timing of subregional glacial ice maxima (Fig. 6). Reduced numbers of vertebrates or their true absence in extreme climate conditions would have limited or excluded human subsistence. The results of this study do not document direct evidence glacial refugia able to support animals and humans spanning the western expansion and decay of the CIS. Instead, they point to areas habitable by animals and human groups before and after glacial ice maxima and establish new age constraints for coastal migration theories of human entry into the Americas on a north Pacific coast route.

Southeast Alaska

In Southeast Alaska, the CIS extended along major fjords and reached the western edge continental shelf in some locations75,76. Ice flow onto subaerially exposed areas of the inner shelf may have left some ice-free areas76, including land now submerged by post-glacial sea level rise and portions of the currently terrestrial land base. These terrestrial areas were assessed in studies that recovered vertebrate remains and archaeological materials77,78. An ice sheet chronology was then constructed based on nine cosmogenic 10Be exposure-dated rock surfaces at previously mapped terrestrial sites. These averaged 17 ka ± 700 calBP and indicated refugia were not continuously exposed but were covered by ice during the CIS maximum79. A recalibration of the radiocarbon date series in77 further suggested that ice advanced over Prince of Wales Island between about 19.8 ka calBP and 17.2 ka calBP and with the ice sheet chronology placed the western extent of the CIS in Southeast Alaska between about 20–17 ka ago79.

Using current methods, this study recalibrated a Southeast Alaska vertebrate date series77 and found the hiatus spanned 18.82 ka calBP and 17.7 ka calBP, which is no less than 1,120 years (Fig. 2). This gap marks the maximum ice extent, a real or near absence of vertebrates, and low potential for human subsistence, migration, and settlement in Southeast Alaska.

The earliest archaeological site in this subregion is Shuká Káa / On Your Knees Cave that dates to about 12.08 ka calBP78. Any earlier undocumented human arrivals would have found a nearly continuous availability of animal resources that could have afforded diverse subsistence opportunities. Areas of the continental shelf that may have been subaerially exposed due to changes in local relative sea level during the Late Wisconsin remain unexplored for archaeological or biological evidence of refugia.

Haida Gwaii

The radiocarbon record on Haida Gwaii follows glacial ice decay. Based on radiocarbon dated plant remains at Mary Point there was a lowland area approximately 80 kms long near the east coast of Moresby Island called the Hecate Refugium that remained ice-free between about 27.96 ka calBP (23.74 ka ± 300 14C BP) and 23.27 ka calBP (19.27 ka ± 360 14C BP)73. The CIS maximum occurred in the Haida Gwaii subregion between about 23.3 ka calBP and 19 ka calBP74,80, and Haida Gwaii was largely ice free by 18.8 ka calBP (15.5 ka 14C BP)47,48. Although no continuously unglaciated area spanning the CIS maximum has been documented, small refugia as nunataks, on headlands and inter-fjord ridges, or as now submerged areas in western Hecate Strait may have remained unglaciated74. By 15.6 ka ago (13 ka 14C BP) the adjacent mainland at Prince Rupert was ice free63.

An ursid bone dated to 17.3 ka years ago (14.54 ka ± 70 14C BP) is an earliest post-ice vertebrate record. The near lack of vertebrate remains and radiocarbon dates for Haida Gwaii before glaciation and immediately following ice decay until about 13.3 ka ago indicates either that the environment did not support continuous occupation, that the preservation of animal bones is limited, or that there is a gap in research. Karst caves on Haida Gwaii have been systematically targeted in archaeological surveys that produced faunal specimens and archaeological materials35,81,82,83,84, which contradicts a gap in research. Sediments removed with glacial meltwater pulses or other preservation issues may explain a near lack of vertebrate remains in karst caves both before and immediately after the CIS maximum. If sediments were removed with glacial meltwater, the radiocarbon record from 13.3 ka calBP may represent a post-glacial stabilization of terrestrial terrain conducive to continuous habitation by animals and humans.

Initial human occupation of Haida Gwaii occurred at Gaduu Din 1 Cave from about 13.54 ka calBP and approximately corresponds with a vertebrate record that includes ursids, ungulates, and salmon as available human food species82,83,84. This suggests that on Haida Gwaii, as in Southeast Alaska, humans populated an ecologically rich environment millennia after the CIS decayed. Haida Gwaii probably was available for migrating humans as ice advanced before about 23.3 ka ago and as ice decayed after 18.8 ka ago, although may not have been viable for human habitation and subsistence following deglaciation until 17.3 ka ago or later.

Central Coast

Glaciomarine sedimentation in marine core MD02-2496 obtained west of central Vancouver Island signals an initial advance of the CIS at about 30 ka ago (25.6 ka 14C BP)85. Ice progressed onto the continental shelf proximal to the core after 20.1 ka calBP (16.7 ka 14C BP) and was thickest on northern Vancouver Island after ca. 19.2 ka ago (16 ka 14C BP)63. A 10Be dating chronology of deglaciation in the Queen Charlotte Sound area north of Vancouver Island indicated that the western margin of the CIS was retreating there by 18.1 ± 0.2 ka ago and low altitude terrain was ice free by 17.7 ± 0.3 ka ago86. Sediments and plant debris show that deglaciation had commenced on northeast Vancouver Island as early as 16.49 ka ago (13.63 ± 0.31 ka 14C BP)87,88. Increased sedimentation rates resulting from the deposition of ice-rafted debris in marine core PAR85-01 retrieved near southwest Queen Charlotte Sound suggests rapid deglaciation commenced from about 18.87 ka calBP (15.57 ± 0.17 ka 14C BP) and continued to 16.43 ka ago (13.59 ± 0.2 ka 14C BP)80. Deposition of detritus in marine core MD02-2496 from about 17 ka calBP (14 ka 14C BP) abruptly terminates 16.09 ka ago (13.5 ka 14C BP) signalling the cessation of rapid ice sheet retreat from the continental shelf west of Vancouver Island. A saw-toothed pattern of deposition in that core records smaller pulses of ice expansion and decay that include a notable event at 14.7 ka ago (12.5 ka 14C BP) coincident with a possible Oldest Dryas ice readvance and massive ice sheet unloading evidenced in extremely rapid isostatic response72,85,89. The CIS persisted until about 12.5 ka ago (10.5 ka 14C BP)63.

A diverse faunal community was present during the CIS ice advance on northwest Vancouver Island and until 19.2 ka ago67. As the CIS expanded westward and covered Vancouver Island, vertebrate faunas perished or relocated to unglaciated areas. Vertebrates recolonized northeast Vancouver Island as early as about 14.9 ka ago90,91 and northwest Vancouver Island by about 14.36 ka ago92. Several species including mountain goats93, deer mice94, and brown bears90 probably arrived on Vancouver Island from south of the CIS margin.

A gap in the vertebrate record of the central coast from about 19.7 ka calBP to 14.9 ka calBP is generally consistent with geological indicators of maximum glacial ice extent and extends well into the span of ice decay. The earliest post-ice vertebrate record occurs some 2 ka after the western margin of the CIS had retreated significantly exposing low altitude terrain. This may signal a period of biotic development and delayed animal recolonizations that could have limited human food resources. Archaeological sites in the central coast subregion currently date to between 14–11.5 ka ago35 in a developed marine and terrestrial biotic setting.

Future archaeological studies on the central coast could identify and target low altitude terrain that was ice free by about 18 ka. Additionally, grounded glaciers might only have reached part way across the continental shelf95,96 and portions of the shelf including Goose, Cook and Middle banks might have been terrestrial landforms or shoals when the CIS was proximal97, affording any migrating human groups access to watercraft landing areas as well as nearshore marine foods and any surviving terrestrial resources. These now-submerged areas have not yet been explored for archaeological evidence.

South Coast

In the south coast subregion, the CIS thickened to the extent that it covered the Vancouver Island Mountains63. The CIS advanced west onto the continental shelf about 19.3–20.5 ka ago (16–17 ka 14C BP), reached maximum southern extent in the Puget Lowland at about 17.7 ka ago (14.5 ka 14C BP)98, and then retreated. Ice decay occurred rapidly as frontal retreat and downwasting98 and caused marine incursion into Juan De Fuca Strait 16.3 ka ago (13.6 ka 14C BP)85. Vancouver and Victoria were ice free by 15.7 ka ago (13.1 ka 14C BP), and glaciers had largely disappeared from this subregion by 12.5 ka ago (10 ka 14C BP)63.

Near the onset of the Late Wisconsin Fraser Glaciation, vertebrates on the south coast included extinct Pleistocene species in parkland and cold steppe grassland environments99. After 20.5 ka calBP, a gap in the vertebrate record corresponds with the CIS maximum. Stellar sea lions had colonized waters near Courtney at 13.66 ka calBP100. By 13.9 ka calBP bison were on southern Vancouver Island and the San Juan Islands101, and mastodon were on the Olympic Peninsula at Sequim68,69. Archaeological evidence of human hunting appears to occur directly with mastodon bones at 13.92 ka calBP at Manis68,69 and on bison bones at 13.91 ka calBP from the Ayer70. This suggests that human subsistence relied at least in part on large terrestrial animals in this period on the south coast. It is unclear if Manis and Ayer predate the Clovis archaeological culture or not because there are no directly and securely dated Clovis sites in the Pacific Northwest with which to compare them. Clovis92,102 and Clovis-style103 artifacts as surface finds and Clovis artifacts at the East Wenatchee site are not directly dated104,105. Clovis in the study area could be slightly younger or older than the established 13.59–12.74 ka calBP Clovis age range.

Human migration and settlement are least likely during CIS ice cover from 20.5 ka calBP to about 17.7 ka calBP and subsistence resources may have been limited as glacial ice decayed to as late as around 13.9 ka calBP.

Coastal Migration

Human migrations into the Americas along the north Pacific coast would have depended on a route without physical barriers and the availability of subsistence resources. The western expansion and retreat of the CIS largely controlled the amount and quality of habitable terrain available for any human groups along the coast. Because boat-based human coastal migration required periodic landfall that would have been obstructed by glaciers, the existence of a chain of ice-free refugia to host human migration during the last glacial is integral to coastal migration theories4,30,37. The availability of subsistence and food sources would have been essential and may have included terrestrial resources or been fully marine15,37,83.

This study found no evidence in the vertebrate and archaeological records of refugia spanning the entire CIS western expansion and retreat on the north Pacific coast. Instead, two main constraints on human migrations are highlighted: (1) the CIS maximum was a physical barrier to migration that denotes when human migrations are unlikely to have occurred, and (2) an apparent decline or absence of vertebrates may signal times of reduced biotic activity and limited human subsistence resources immediately before, during and for hundreds of years and longer durations after CIS maxima. The current archaeological record in the study area occurs after CIS maxima, near the end of glacial ice decay, and is consistant with these constraints.

To firmly establish the north Pacific coast as a route by which humans are likely to have migrated from Beringia into southern North America, archaeological sites on the coast should pre-date those to the south. The current archaeological record starts approximately 14 ka ago. This is somewhat later than although generally consistent with the age of earliest securely dated archaeological sites south of the ice sheets in the 16–14.5 ka old range. Future archaeological research on the north Pacific coast may well discover other early sites that post-date glacial ice maxima and are in the 18–15 ka age range.

If a 21–23 ka old record of human footprints at White Sands is confirmed or other sites of a similar age are found, archaeological evidence on the north Pacific coast that matches or pre-dates the record to the south will be needed to strongly support costal migration theory and a Pacific coastal route from Beringia into southern North America. Toward that end, this study shows that coastal terrain hosted vertebrates and could have been accessed by human groups before CIS ice cover in Southeast Alaska 18.8 ka ago, on Haida Gwaii likely prior to about 23.3 ka ago, and in the central and south coast subregions before 19.7 ka ago.

Conclusions

The ages of vertebrate specimens and archaeological sites signal environments suitable for human subsistence and settlement across the Late Wisconsin expansion and decay of the CIS on the north Pacific coast of North America. Four radiocarbon date series reveal gaps during CIS western ice maxima when human groups are least likely to have migrated or settled. In Southeast Alaska, the vertebrate record is nearly continuous with a hiatus from about 17.7–18.82 ka calBP at an ice maximum. On Haida Gwaii, a gap in the vertebrate record corresponds with ice extent from around 23–19 ka and then persists to 17.31 ka calBP and 13.3 ka calBP, which may point to periodic vertebrate colonisations. On the central coast, the ice maximum spans from about 20.1–18.5 ka calBP. A hiatus in the vertebrate record occurs from 19.2–14.9 ka calBP on north Vancouver Island and animals and humans occur as early as 13.9 ka ago on Triquet and Calvert islands. On the south coast, a gap in the vertebrate record occurs during the ice maximum from 20.5–17.7 ka calBP and continues to about 13.9 ka calBP when humans and vertebrates co-occur. This record indicates that a corridor in front of the expanding CIS would have been substantially open for human migrations along the north Pacific coast during the Late Wisconsin until about 23.3 and 20 ka years ago, after which glacial ice cover probably hindered migrations until about 18.9 ka and 17.7 or 17 ka years ago. A coastal route is likely to have been at least partially open during initially rapid CIS decay and gaps in the vertebrate record to as late as about 14 ka years ago suggest reduced biotic activity may have challenged human subsistence. These age ranges define physical and subsistence constraints on human migrations for coastal migration theories in the peopling of the Americas debate.

Methods

The 233 radiocarbon dates on vertebrate specimens analysed in this study are from published sources (Table S1). These originate from several laboratories that are indicated by the sample name and number. Laboratory naming conventions are as follows: AA—University of Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) Laboratory, USA; Beta—Beta Analytic, USA; CAMS—Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, USA; GaK—Gakushūin University, Japan; GX—Geochron Laboratories, Inc., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; OxA—Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, University of Oxford, UK; TO—IsoTrace Laboratory, University of Toronto, Canada; UCIAMS—Keck-CCAMS Group, Irvine, California, USA; UOC—A.E. Lalonde AMS Laboratory, University of Ottawa, Canada; WAT—University of Waterloo, Canada; and WSU—Washington State University, USA.

OxCal v 4.4.4 was used to calculate calendar age estimates from radiocarbon age determinations and for probabilistic Bayesian modeling of calibrated 14C determinations following64. Radiocarbon age determinations reported previously were recalibrated. Age estimates on terrestrial samples were calibrated based on atmospheric data from IntCal2065. Those on marine samples were calibrated based on data from Marine2066. Marine reservoir offsets in marine samples were calculated using ΔR values from the 14CHRON Marine20 marine radiocarbon reservoir database at http://calib.org/marine/106. The ΔR values in that database have been recalculated to provide a ΔR20 for use with Marine20107. Marine offset values vary in subregions from south to north along the north Pacific coast108. To account for this variation, averaged ΔR values were calculated using published datapoints in the 14CHRON Marine database. A ΔR value of 257 ± 99 based on the weighted average offset of 32 datapoints (Table S6) was applied to marine samples from Southeast Alaska and Haida Gwaii. A ΔR value of 267 ± 52 based on the weighted average offset of 19 datapoints (Table S6) was applied to marine samples from the south coast subregion.

Radiocarbon samples previously identified as mixed marine and terrestrial were assigned a percent marine amount based on δ13C and δ15N values for each analyzed bone sample (Table S7). I used the FRUITS 3.0 Beta program109 to model the proportional contributions of terrestrial and marine food sources to the value of the δ13C and δ15N isotopes. Where δ 15N was not published with a radiocarbon date, I estimated this value based on δ 15N values from published sources that best match the spatial and temporal resources available to the mixed feeders in this study to avoid issues associated with baseline shifts and Suess effects110. The bone collagen-collagen trophic enrichment factor of δ13C 1.0 ± 0.3‰ and δ15N 4.2 ± 1.4‰ based on data from archaeological sites111 was used.

A radiocarbon date of 14,390 ± 70 (CAMS 75,746) on a bear bone from Haida Gwaii was noted as a mixed feeder81. No stable isotope values were reported with this sample. However,81 stated that “…an estimated correction of − 150 years has been applied to CAMS 75,746.” To calibrate this date, I added 150 to the reported age of 14,390 ± 70 14C BP and used the age determination 14,540 ± 70 14C BP with ΔR 257 ± 99 and an estimated 30% marine diet in the OxCal calibration model (Table S7).

Radiocarbon ages, 14C, are reported as before present, BP. Calibrated radiocarbon age estimates are indicated as calendar years before present, calBP. In both instances, the present age refers to Gregorian years before mid-1950 CE. The abbreviation “ka” indicates thousands of years (kiloannus). The results of calibrations are given as median age estimates and as age ranges that are 95.4% confidence intervals.

Data availability

All data, code, and materials used in the analyses are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References

Haynes, C. V. Jr. Fluted projectile points: Their age and dispersion. Science 145, 1408–1413 (1966).

Haynes, C. V. Jr. The earliest Americans. Science 166, 709–715 (1969).

Martin, P. S. The discovery of America: The first Americans may have swept the Western Hemisphere and decimated its fauna within 1000 years. Science 179, 969–974 (1973).

Fladmark, K. R. Routes: Alternate migration corridors for early man in North America. Am. Antiq. 44, 55–69 (1979).

Mead, J. I. Is it really that old? A comment about the Meadowcroft Rockshelter “overview”. Am. Antiq. 45, 579–582 (1980).

Grayson, D. K. Archaeological associations with extinct Pleistocene mammals in North America. J. Archaeol. Sci. 11, 213–221 (1984).

Dillehay, T. D. Monte Verde. Science 245, 1436 (1989).

Holliday, V. T. Paleoindian Geoarchaeology of the Southern High Plains (University of Texas Press, 1997).

Meltzer, D. J. et al. On the Pleistocene antiquity of Monte Verde, southern Chile. Am. Antiq. 62, 659–663 (1997).

Adovasio, J. M., Pedler, D. R., Donahue, J. & Stuckenrath, R. Two decades of debate on Meadowcroft Rockshelter. North American Archaeologist 19, 317–341 (1999).

Dixon, E. J. Bones, boats, and bison: Archeology and the first colonization of Western North America (University of New Mexico Press, 1999).

Grayson, D. K. & Meltzer, D. J. A requiem for North American overkill. J. Archaeol. Sci. 30, 585–593 (2003).

Fiedel, S. J. & Haynes, G. A premature burial: Comments on Grayson and Meltzer’s “Requiem for overkill”. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 121–131 (2004).

Madsen, D. B. (ed.) Entering America: Northeast Asia and Beringia before the Last Glacial Maximum (The University of Utah Press, 2004).

Erlandson, J. M. et al. The kelp highway hypothesis: Marine ecology, the coastal migration theory, and the peopling of the Americas. J. Isl. Coastal Archaeol. 2, 161–174 (2007).

Firestone, R. B. et al. Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 16016–16021 (2007).

Waters, M. R. & Stafford, T. W. Jr. Redefining the age of Clovis: Implications for the peopling of the Americas. Science 315, 1122–1126 (2007).

Tamm, E. et al. T Beringian standstill and spread of Native American founders. PLOS ONE 2, e829 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000829 (2007).

Haynes, G. et al. Comment on "Redefining the age of Clovis: Implications for the peopling of the Americas”. Science 317, 320 (2007).

Dillehay, T. D. et al. Monte Verde: Seaweed, food, medicine, and the peopling of South America. Science 320, 784–786 (2008).

Goebel, T., Waters, M. R. & O’Rourke, D. H. The late Pleistocene dispersal of modern humans in the Americas. Science 319, 1497 (2008).

Meltzer, D. J. First peoples in a new world: Colonizing ice age America (University of California, 2009).

Jenkins, D. L. Clovis age Western Stemmed projectile points and human coprolites at the Paisley Caves. Science 337, 223–228 (2012).

Stanford, D. J. & Bradley, B. Across Atlantic ice: The origin of America's Clovis culture (University of California Press, 2012).

Graf, K. E. et al. (eds) Paleoamerican Odyssey (Texas A&M Univ. Press, 2014).

Holliday, V. T., Meltzer, D. J., Grayson, D. K., Surovell, T. & Boslough, M. The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis: A cosmic catastrophe. J. Quat. Sci. 29, 525–530 (2014).

O’Brien, M. et al. On thin ice: Problems with Stanford and Bradley’s proposed Solutrean colonisation of North America. Antiquity 88, 606–613 (2014).

Grayson, D. K. & Meltzer, D. J. Revisiting Paleoindian exploitation of extinct North American mammals. J. Archaeol. Sci. 56, 177–193 (2015).

Hoffecker, J. F., Elias, S. A., O’Rourke, D. H., Scott, G. R. & Bigelow, N. H. Beringia and the global dispersal of modern humans. Evol. Anthropol. 25, 64–78 (2016).

Braje, T. J., Dillehay, T. D., Erlandson, J. M., Klein, R. G. & Rick, T. C. Finding the first Americans. Science 358, 592–594 (2017).

Bourgeon, L., Burke, A. & Higham, T. Earliest human presence in North America dated to the Last Glacial Maximum: New radiocarbon dates from Bluefish Caves, Canada. PLOS ONE 12, e0169486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169486 (2017).

Waters, M. R. et al. Pre-Clovis projectile points at the Debra L. Friedkin site, Texas—Implications for the late Pleistocene peopling of the Americas. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat4505 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat4505 (2018).

Moreno-Mayar, J. V. et al. Early human dispersals within the Americas. Science 362, 1–28 (2018).

Potter, B. A. et al. Current evidence allows multiple models for the peopling of the Americas. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5473 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat5473 (2018).

McLaren, D. et al. Late Pleistocene archaeological discovery models on the Pacific Coast of North America. PaleoAmerica 6, 43–63 (2019).

Waters, M. R. Late Pleistocene exploration and settlement of the Americas by modern humans. Science 365, eaat5447 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat5447 (2019).

Davis, L. G. & Madsen, D. B. The coastal migration theory: Formulation and testable hypotheses. Quat. Sci. Rev. 249, 106605 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106605 (2020).

Davis, L. G. et al. Dating of a large tool assemblage at the Cooper’s Ferry site (Idaho, USA) to ~15,785 cal yr B.P. extends the age of stemmed points in the Americas. Sci. Adv. 8, eade1248 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade1248 (2022).

Dillehay, T. D. Monte Verde: A late Pleistocene settlement in Chile, the archaeological context and interpretation Vol. 2 (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

Waters, M. R. et al. The Buttermilk Creek Complex and the origins of Clovis at the Debra L. Friedkin site, Texas. Science 331, 1599–1603 (2011).

Halligan, J. J. et al. Pre-Clovis occupation 14,550 years ago at the Page-Ladson site, Florida, and the peopling of the Americas. Sci. Adv. 2(5), e1600375. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600375 (2016).

Dillehay, T. D. et al. Simple technologies and diverse food strategies of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene at Huaca Prieta, coastal Peru. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602778 https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.160277 (2017).

Williams, T. J. et al. Evidence of an early projectile point technology in North America at the Gault Site, Texas, USA. Sci. Adv. 4(7), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar5954 (2018).

Davis, L. G. et al. Late Upper Paleolithic occupation at Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, USA, ~16,000 years ago. Science 365, 891–897 (2019).

Clark, P. U. et al. The Last Glacial Maximum. Science 325, 710–714 (2009).

Clark, J. et al. The age of the opening of the Ice-Free Corridor and implications for the peopling of the Americas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2118558119 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.211855811 (2022).

Dyke, A. S., Moore, A. & Robertson, L. Deglaciation of North America. Geol. Surv. Can. Open File 1574 (2003).

Dalton, A. S. et al. An updated radiocarbon-based ice margin chronology for the last deglaciation of the North American Ice Sheet Complex. Quat. Sci. Rev. 234, 106223 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106223 (2020).

Burns, J. A. Mammalian faunal dynamics in late Pleistocene Alberta. Canada. Quat. Int. 217, 37–42 (2010).

Heintzman, P. D. et al. Bison phylogeography constrains dispersal and viability of the Ice Free Corridor in western Canada. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 8057–8063 (2016).

Pedersen, M. W. et al. Postglacial viability and colonization in North America’s ice-free corridor. Nature 537, 45–49 (2016).

Mandryk, C., Josenhans, H., Fedje, D. & Mathewes, R. Late Quaternary paleoenvironments of Northwestern North America: Implications for inland versus coastal migration routes. Quat. Sci. Rev. 20, 301–314 (2001).

Mackie, Q., Fedje, D. & McLaren, D. Archaeology and sea level change on the British Columbia Coast. CJA 42, 74–91 (2018).

Bennett, M. R. et al. Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 373, 1528–1531 (2021).

Madsen, D. B., Davis, L. G., Rhode, D. & Oviatt, C. G. Comment on “Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum”. Science 374, eabm4678 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abg7586 (2022).

Haynes, C. V. Jr. Evidence for humans at White Sands National Park during the Last Glacial Maximum could actually be for Clovis people ∼13,000 years ago. PaleoAmerica 8, 95–98 (2022).

Pigati, J. S. et al. Response to Comment on “Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum”. Science 375, eabm6987 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm6987 (2022).

Pigati, J. S. et al. Reply to “Evidence for humans at White Sands National Park during the Last Glacial Maximum could actually be for Clovis people ∼13,000 Years Ago” by C. Vance Haynes, Jr. PaleoAmerica 8, 99–101 (2022).

Rachal, D. M., Mead, J. I., Dello-Russo, R. & Cuba, M. T. Deep-water delivery model of Ruppia seeds to a nearshore/terrestrial setting and its chronological implications for late Pleistocene footprints, Tularosa Basin, New Mexico. Geoarchaeology 37, 923–933 (2022).

Oviatt, C., Madsen, D., Rhode, D. & Davis, L. A. critical assessment of claims that human footprints in the Lake Otero basin, New Mexico date to the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Res. 111, 138–147 (2023).

Rachal, D. M., Dello-Russo, R. & Cuba, M. The Pleistocene footprints are younger than we thought: Correcting the radiocarbon dates of Ruppia seeds, Tularosa Basin, New Mexico. Quat. Res. 1–12 (2024).

Pigati, J. S. et al. Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. Science 382, 73–75 (2023).

Clague, J. J. & Ward, B. Pleistocene Glaciation of British Columbia. Dev. Quat. Sci. 15, 563–573 (2011).

Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360 (2009).

Reimer, P. et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62 (2020).

Heaton, T. J. et al. Marine20—the marine radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55,000 calBP). Radiocarbon 62, 779–820 (2020).

Ward, B. C. et al. Port Eliza cave: North American west coast interstadial environment and implications for human migrations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 1383–1388 (2003).

Gustafson, C. E., Gilbow, D. & Daugherty, R. The Manis Mastodon Site: Early man on the Olympic Peninsula. CJA 3, 157–164 (1979).

Waters, M. R. et al. Pre-Clovis mastodon hunting 13,800 years ago at the Manis Site, Washington. Science 334, 351–353 (2011).

Kenady, S. M., Wilson, M. C., Schalk, R. F. & Mierendorf, R. R. Late Pleistocene butchered Bison antiquus from Ayer Pond, Orcas Island, Pacific Northwest: Age confirmation and taphonomy. Quat. Int. 233, 130–141 (2011).

Clague, J. J. & James, T. S. History and isostatic effects of the last ice sheet in southern British Columbia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 71–87 (2002).

Shugar, D. H. et al. Post-glacial sea-level change along the Pacific coast of North America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 97, 170–192 (2014).

Mathewes, R. W. & Clague, J. J. Paleoecology and ice limits of the early Fraser Glaciation (Marine Isotope Stage 2) on Haida Gwaii, British Columbia. Canada. Quat. Res. 88, 277–292 (2017).

Clague, J. J., Mathewes, R.W. & Agar, T. A. Environments of Northwestern North America before the Last Glacial Maximum in Entering America: Northeast Asia and Beringia before the Last Glacial Maximum (The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT, 2004), pp. 63–94

Mann, D. H. Wisconsin and Holocene glaciation of Southeast Alaska in Glaciation in Alaska (Alaska Geological Society, Anchorage, AK 1986), pp. 237–265

Carrara, P. E., Ager, T. A. & Baichtal, J. F. Possible refugia in the Alexander Archipelago of southeastern Alaska during the Late Wisconsin glaciation. Can. J. Earth Sci. 44, 229–244 (2007).

Heaton, T. H. & Grady, F. The Late Wisconsin vertebrate history of Prince of Wales Island, Southeast Alaska in Ice Age Cave Faunas of North America (Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2003), pp. 17–53.

Dixon, E. J. et al. Late Quaternary regional geoarchaeology of Southeast Alaska karst: a progress report. Geoarchaeology 12, 689–712 (1997).

Lesnek, A. J., Briner, J. P., Lindqvist, C., Baichtal, J. F. & Heaton, T. H. Deglaciation of the Pacific coastal corridor directly preceded the human colonization of the Americas. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar5040. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar5040 (2018).

Blaise, B., Clague, J. J. & Mathewes, R. W. Time of maximum late Wisconsinan Glaciation, west coast of Canada. Quat. Res. 47, 140–146 (1990).

Ramsey, C., Griffiths, P., Fedje, D., Wigen, R. & Mackie, Q. Preliminary investigation of a Late Wisconsinan fauna from K1 Cave, Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii) Canada. Quat. Res. 62, 105–109 (2004).

Mackie, Q., Fedje, D., McLaren, D., Smith, N., McKechnie, I. Early environments and archaeology of coastal British Columbia. In Trekking the Shore: Changing Coastlines and the Antiquity of Coastal Settlement 51–103 (Springer, New York, 2011).

Fedje, D. W., Mackie, Q., Lacourse, T. & McLaren, D. Younger Dryas environments and archaeology on the Northwest Coast of North America. Quat. Int. 242, 452–462 (2011).

Fedje, D., Mackie, Q., Smith, N. & McLaren, D. Function, visibility, and interpretation of archaeological assemblages at the Pleistocene/Holocene transition in Haida Gwaii in From the Yenisei to the Yukon: Interpreting Lithic Assemblage Variability in Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene Beringia (Texas A&M University Press, College Station, TX, 2011), pp. 323–342

Cosma, T. N., Hendy, I. L. & Chang, A. S. Chronological constraints on Cordilleran Ice Sheet glaciomarine sedimentation from core MD02-2496 off Vancouver Island (Western Canada). Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 941–955 (2008).

Darvill, C. M., Menounos, B., Goehring, B. M., Lian, O. B. & Caffee, M. W. Retreat of the western Cordilleran Ice Sheet margin during the last deglaciation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 9710–9720 (2018).

Howes, D. E. Late Quaternary sediments and geomorphic history of northern Vancouver Island British Columbia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 20, 57–65 (1983).

Hebda, R. J. Late-glacial and postglacial vegetation history at Bear Cove bog, Northeast Vancouver Island British Columbia. Can. J. Bot. 61, 3172–3192 (1983).

Mathews, W. H., Fyles, J. G. & Nasmith, H. W. Postglacial crustal movements in southwestern British Columbia and adjacent Washington State. Can. J. Earth Sci. 7, 690–702 (1970).

Steffen, M. L. & Fulton, T. L. On the association of giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) and brown bear (Ursus arctos) in late Pleistocene North America. Geobios 51, 61–74 (2018).

Steffen, M. L. Late Pleistocene heather vole, Phenacomys, on the North Pacific Coast of North America: Environments, local extinctions, and archaeological implications. Can. J. Earth Sci. 59, 708–721 (2022).

Al-Suwaidi, M. et al. Late Wisconsinan Port Eliza Cave sediments and their implications for human coastal migration, Vancouver Island Canada. Geoarcheology 21, 307–332 (2006).

Shafer, A. B., Côté, S. D. & Coltman, D. W. Hot spots of genetic diversity descended from multiple Pleistocene refugia in an alpine ungulate. Evolution 65, 125–138 (2011).

Sawyer, Y. E., Flamme, M. J., Jung, T. S., MacDonald, S. O. & Cook, J. A. Diversification of deer mice (Rodentia: genus Peromyscus) at their north-western range limit: Genetic consequences of refugial and island isolation. J. Biogeogr. 44, 1572–1585 (2017).

Luternauer, J. L. & Murray, J. W. Late Quaternary morphologic development and sedimentation, central British Columbia continental shelf (Paper 83–21, Geol. Surv. Can., 1983).

Herzer, R. H. & Bornhold, B. D. Glaciation and post-glacial history of the continental shelf off southwestern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Mar. Geol. 48, 285–319 (1982).

Luternauer, J. L. et al. Late Pleistocene terrestrial deposits on the continental shelf of western Canada: Evidence for rapid sea-level change at the end of the last glaciation. Geology 17, 357–360 (1989).

Porter, S. C. & Swanson, T. W. Radiocarbon age constraints on rates of advance and retreat of the Puget lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet during the last glaciation. Quat. Res. 50, 205–213 (1998).

Steffen, M. L. & Harington, C. R. Giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) from Late Wisconsinan deposits at Cowichan Head, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 47, 1029–1036 (2010).

Harington, C. R., Ross, R. L. M., Mathewes, R. W., Stewart, K. M. & Beattie, O. A late Pleistocene Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus) from Courtenay, British Columbia: its death, associated biota, and paleoenvironment. Can. J. Earth Sci. 41, 1285–1297 (2004).

Wilson, M. C., Kenady, S. M. & Schalk, R. F. Late Pleistocene Bison antiquus from Orcas Island, Washington, and the biogeographic importance of an early postglacial land mammal dispersal corridor from the mainland to Vancouver Island. Quat. Res. 71, 49–61 (2009).

Croes, D. R. et al. The Projectile Point Sequences in the Puget Sound Region in Projectile Point Sequences in Northwestern North America (Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, 2008), pp. 105–130

McLaren, D. The occupational history of the Stave Watershed in Archaeology of the Lower Fraser River Region (Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, 2017), pp. 149–158

Gramly, R. M. The Richey Clovis Cache: Earliest Americans Along the Columbia River (Persimmon Press, Buffalo, NY, 1993)

Kilby, J. D. & Huckell, B. B. Clovis caches: Current perspectives and future directions in PaleoAmerican Odyssey (Texas A&M University Press, Austin, TX, 2014), pp. 257–272

Reimer, P. J. & Reimer, R. W. A marine reservoir correction database and on-line interface. Radiocarbon 43, 461–463 (2001).

Heaton, T. et al. A response to community questions on the Marine20 radiocarbon age calibration curve: Marine reservoir ages and the calibration of 14C samples from the oceans. Radiocarbon 65, 247–273 (2023).

Edge, D. et al. A modern multicentennial record of radiocarbon variability from an exactly dated bivalve chronology at the Tree Nob site (Alaska). Radiocarbon 65, 81–96 (2022).

Fernandes, R., Millard, A. R., Brabec, M., Nadeau, M.-J. & Grootes, P. Food reconstruction using isotopic transferred signals (FRUITS): A Bayesian model for diet reconstruction. PLOS ONE 9, e87436. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087436 (2014).

Keeling, R. F. et al. Atmospheric evidence for a global secular increase in carbon isotopic discrimination of land photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 10361–10366 (2017).

Bocherens, H. Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 117, 42–71 (2015).

Dixon, E. J. Human colonization of the Americas: Timing, technology and process. Quat. Sci. Rev. 20, 277–299 (2001).

Davis, S. D. (ed.). The Hidden Falls Site, Baranof Island, Alaska (Alaska Anthropological Association Monograph Series, vol. 5, Brockport, 1989).

Ackerman, R. E., Ground Hog Bay, site 2 in American Beginnings: The Prehistory and Palaeoecology of Beringia (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 1996), pp. 424-429

Ackerman, R. E., Hamilton, T. D. & Stuckenrath, R. Early culture complexes on the Northern Northwest Coast. CJA 3, 195–209 (1979).

Mathewes, R. W., Richards, M. & Reimchen, T. E. Late Pleistocene age, size, and paleoenvironment of a caribou antler from Haida Gwaii British Columbia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 56, 688–692 (2019).

Mathewes, R. W., Lian, O., Clague, J. J. & Huntley, M. Early Wisconsinan (MIS 4) Glaciation on Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, and implications for biological refugia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 52, 939–951 (2015).

Fedje, D.W., Mackie, Q., McLaren, D. S. & Christensen, T. A. projectile point sequence for Haida Gwaii in Projectile Point Sequences in Northwestern North America (Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, 2008), pp. 19–40

Steffen, M. L. & Mackie, Q. An experimental approach to understanding burnt fish bone assemblages within archaeological hearth contexts. Can. Zooarch. 23, 11–38 (2005).

Mackie, A. P. & Sumpter, I. D. Shoreline settlement patterns in Gwaii Haanas during the early and late Holocene in Haida Gwaii, Human History and Environment from the Time of Loon to the Time of the Iron People (UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, 2005), pp. 337–371

Carlson, R. L. Early Namu in Early Human Occupation in British Columbia (UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, 1995), pp. 83–102

Cannon, A. The economic prehistory of Namu: Patterns in vertebrate Fauna (Archaeology Press, 1991).

Cannon, A. Settlement and sea-levels on the Central Coast of British Columbia: Evidence from shell midden cores. Am. Antiq. 65, 67–77 (2000).

McLaren, D. et al. Terminal Pleistocene Epoch human footprints from the Pacific Coast of Canada. PLOS ONE 13, e0193522. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193522 (2018).

Gauvreau, A. et al. Geo-archaeology and Haíɫzaqv oral history: Long-term human investment and resource use at EkTb-9, Triquet Island, N̓úláw̓itxˇv tribal area, Central Coast, British Columbia Canada. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 49, 103884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.103884 (2023).

Carlson, C. C. The Bear Cove fauna and the subsistence history of Northwest Coast maritime culture in Archaeology of Coastal British Columbia: Essays in Honour of Professor Philip M. Hobler (Simon Fraser University Archaeology Press, Burnaby, BC, 2003), pp. 65–86.

Carlson, R. L. Cultural antecedents in Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 7, Northwest Coast (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 1990), pp. 60–69.

Steffen, M. L. Body-size trends in Peromyscus (Rodentia: Cricetidae) on Vancouver Island, Canada, with comments on relictual gigantism. Paleobiology 42, 532–546 (2016).

Nagorsen, D. W. & Keddie, G. Late Pleistocene mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) from Vancouver Island: Biogeographic implications. J. Mammal. 81, 666–675 (2000).

Nagorsen, D. W., Keddie, G. & Hebda, R. J. Early Holocene black bears, Ursus americanus, from Vancouver Island. Can. Field-Nat. 109, 11–18 (1995).

Fedje, D. et al. A revised sea level history for the northern Strait of Georgia, British Columbia Canada. Quat. Sci. Rev. 192, 300–316 (2018).

Fedje, D. et al. Slowstands, stillstands and transgressions: Paleoshorelines and archaeology on Quadra Island, BC Canada. Quat. Sci. Rev. 270, 107161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107161 (2021).

Matson, R. G. The Old Cordilleran component at the Glenrose Cannery site in Early Human Occupation in British Columbia (UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, 1996), pp. 111–122.

Matson, R. G. & Coupland, G. The Prehistory of the Northwest Coast (Academic Press, 1996).

McLaren, D. & Steffen, M. L. A sequence of formed bifaces from the Fraser Valley Region of British Columbia in Projectile Point Sequences in Northwestern North America (Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, 2008), pp. 87–104

Harington, C. R. Quaternary animals: Vertebrates of the ice age. in Life in Stone: A Natural History of British Columbia’s Fossils 259–273 (UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, 1996).

Barton, B. R. Notes on the new Washington State fossil. Mammuthus columbi. Wash. Geol. 26, 68 (1998).

Blake Jr., W. Geological Survey of Canada radiocarbon dates XXII (Paper 82–7, Geol. Surv. Can., 1982).

Hebda, R. J. & Spalding, D. A. E. Fossils and museums: Windows into ancient worlds. in Life in Stone: A Natural History of British Columbia’s Fossils 14–24 (UBC Press, Vancouver, BC, 1996).

Mustoe, G. E., Harington, C. R. & Morlan, R. E. Cedar Hollow, an early Holocene faunal site from Whidbey Island Washington. West. N. Am. Nat. 65, 429–440 (2005).

Petersen, K. L., Mehringer, P. J. & Gustafson, C. E. Late-glacial vegetation and climate at the Manis Mastadon Site, Olympic Peninsula Washington. Quat. Res. 20, 215–231 (1983).

Haynes, C. V. Jr. & Huckell, B. B. The Manis mastodon: An alternative interpretation. PaleoAmerica 2, 189–191 (2016).

Lehner, N. S. Arctic fox winter movements and diet in relation to industrial development on Alaska’s North Slope (University of Alaska Fairbanks, AK, 2012).

West, C. F. & France, C. A. Human and canid dietary relationships: Comparative stable isotope analysis from the Kodiak Archipelago. Alaska. J. Ethnobiol. 35, 519–535 (2015).

Plint, T., Longstaffe, F. J., Ballantyne, A., Telka, A. & Rybczynski, N. Evolution of woodcutting behaviour in Early Pliocene beaver driven by consumption of woody plants. Sci. Rep. 10, 13111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70164-1 (2020).

Steffen, M. L. Coast-proximal inland archaeology and the Vancouver Island marmot (Marmota vancouverensis). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 36, 102863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102863 (2021).

Jürgensen, J. et al. Diet and habitat of the saiga antelope during the late Quaternary using stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios. Quat. Sci. Rev. 160, 150–161 (2017).

Fox-Dobbs, K., Leonard, J. A. & Koch, P. L. Pleistocene megafauna from eastern Beringia: Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental interpretations of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope and radiocarbon records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 261, 30–46 (2008).

Byers, D. A., Yesner, D. R., Broughton, J. M. & Coltrain, J. B. Stable isotope chemistry, population histories and late Prehistoric subsistence change in the Aleutian Islands. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 183–196 (2011).

Coltrain, J. B., Hayes, M. G. & O’Rourke, D. H. Sealing, whaling and caribou: The skeletal isotope chemistry of eastern Arctic foragers. J. Archaeol. Sci. 31, 39–57 (2004).

Moss, M. L. et al. Historical ecology and biogeography of North Pacific pinnipeds: Isotopes and ancient DNA from three archaeological assemblages. J. Island Coast. Archaeol. 1, 165–190 (2006).

Szpak, P., Orchard, T. J., McKechnie, I. & Gröcke, D. R. Historical ecology of late Holocene sea otters (Enhydra lutris) from northern British Columbia: Isotopic and zooarchaeological perspectives. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39, 1553–1571 (2011).

McNeely, R., Dyke, A. S. & Southon, J. R. Canadian marine reservoir ages, preliminary data assessment. Geol. Surv. Can. Open File 5049 (2006).

Robinson, S. W. & Thompson, G. Radiocarbon corrections for marine shell dates with application to southern Pacific Northwest Coast prehistory. Syesis 14, 45–57 (1981).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L.S. conceptualized the study, conducted the literature review, prepared the figures, and wrote and reviewed the manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Steffen, M.L. New age constraints for human entry into the Americas on the north Pacific coast. Sci Rep 14, 4291 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54592-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54592-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.