Abstract

Managing contradictions and building resilience help us overcome life's challenges. Here, we explored the link between attitudes towards contradictions and psychological resilience, examining the role of cortical conflict resolution networks. We enlisted 173 healthy young adults and used questionnaires to evaluate their cognitive thinking styles and resilience. They underwent structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging scans. Our results revealed that contrasting attitudes toward contradictions, formal logic, and naïve dialecticism thinking styles corresponded with varying degrees of resilience. We noted structural and functional differences in brain networks related to conflict resolution, including the inferior frontal and parietal cortices. The volumetric variations within cortical networks indicated right-hemispheric lateralization in different thinking styles. These findings highlight the potential links between conflict resolution and resilience in the frontoparietal network. We underscore the importance of frontoparietal brain networks for executive control in resolving conflicting information and regulating the impact of contradictions on psychological resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adversity is an inherent aspect of life, impacting people to varying degrees. While some individuals can quickly recover from setbacks, others find it challenging. This perspective is closely tied to the concept of psychological resilience, which empowers individuals to navigate life's ups and downs with balance and composure. Attitudes towards contradictions, as proposed by Peng and Nisbett1, offer valuable insights into an individual's mindset and, consequently, their capacity for psychological resilience1. Contradictions are an intrinsic part of life, presenting challenges that can be viewed as either insurmountable obstacles or opportunities for personal growth. People with a holistic thinking style tend to be more open to embracing contradictions and often possess a more flexible and adaptive mindset compared to those with a more analytical thinking style, which may involve elements of naïve dialecticism and formal logic2,3. This predisposition can be evaluated using the Analysis-Holism scale (AHS)1,3. The subscales employed in the AHS for evaluating attitudes toward contradictions unveiled noticeable distinctions between the two contemplated thinking styles (i.e., formal logic vs. naïve dialecticism).

Furthermore, alongside the AHS, recent cross-cultural studies have revealed a noteworthy connection between an individual's capacity for psychological resilience and traditional Chinese thinking styles, such as the Zhongyong thinking scales (ZTS)4,5. These studies, as outlined in references 4 and 5, underline the significance of balance, harmony, and flexibility in effectively handling conflicting situations. In examining the role of resilience among East Asian populations, one must consider assessments that encapsulate varying cognitive thinking perspectives, specifically the dialectical and logical approaches as interpreted by the AHS, and the continuum of holistic to analytical thought processes as indicated by ZTS4,5. For example, in the Eastern Asian context6, a dialectical perspective may be more conducive to resilience, which embraces multiple viewpoints and their integration, may foster resilience. Furthermore, a recent study7 that explored the structural relationships between Zhongyong, dispositional mindfulness, resilience, and subjective well-being. This study employed structural equation modeling on a sample of 1099 Chinese high school students and provided robust empirical evidence supporting a positive relationship between Zhongyong and resilience. Specifically, the study found that Zhongyong positively predicts resilience, life satisfaction, and positive affect, while also being a significant mediator in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and these outcomes. These findings not only align with our theoretical assertions but also reinforce the empirical link between Zhongyong thinking style and psychological resilience. Given the hypothesized alignment between ZTS and naïve dialecticism in their comprehensive and integrative outlooks, it becomes imperative to delve into their interrelations.

One potential link between ZTS and AHS in psychological resilience from Chinese culture prospect is the ability to resolve conflicts and adapt to stress, as effective conflict resolution and adaptability are key factors in developing resilience and managing life's adversities. Yang et al. (2016) have reported that Zhongyong thinking is associated with lower mental distress indicators such as anxiety and depressive symptoms8, and higher subjective well-being indicators like self-esteem and life satisfaction, indicating that Zhongyong thinking could be integrated into emotion regulation strategies, with potential applications in therapy to encourage individuals to consider multiple perspectives, think holistically, acknowledge emotional complexity, and maintain interpersonal harmony. Conflict resolution is also one of the factors for promoting resilience in situations of life's difficulties as it can be a source of stress and negative emotions9,10,11. When individuals are in a conflict situation, their brains are faced with competing demands or goals, and cognitive control allows them to prioritize and focus on the most important or relevant goal while inhibiting or suppressing other, less relevant goals or responses. Conflict resolution can be thought of as a specific application of cognitive control in that it involves using cognitive control processes to regulate thoughts and behaviors to resolve a conflict12,13. Previous neuroimaging studies have investigated the neural correlates of conflict resolution and the attitude toward contradictions in cognitive thinking styles. For instance, the dorsal attention network is involved in allocating attention and selecting relevant information14,15,16. It consists of a network of brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, and superior colliculus, which play critical roles in conflict resolution.

Overview of the present research

In the current study, we aim to investigate the relationship between the attitude toward contradictions, conflict resolution-related cortical brain networks, and psychological resilience in a sample of young healthy individuals. Specifically, we examined the neural correlates of psychological resilience in different attitudes toward contradictions, and conflict resolution-related cortical brain networks using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Neuroanatomical and functional variations in the brain have been linked to diverse cognitive and behavioral tendencies. For instance, variations in certain brain regions have been associated with cognitive and emotional processing differences, which could influence individuals’ resilience capacities17,18. We further hypothesized that people with a dialectical thinking style would be associated with differences in brain regions linked to conflict resolution, such as the inferior frontal regions and parietal areas. These cortical mechanisms associated with conflict resolution play a crucial role in psychological resilience. To test these hypotheses, we recruited a sample of young healthy individuals and administered self-report measures to assess their attitude toward contradictions and psychological resilience. We adopted Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA)19 to reflects individuals’ psychological resilience, we also used advanced fMRI analysis techniques to examine the relationship between the attitude toward contradictions (as measured by AHS), conflict resolution associated cortical brain networks, and psychological resilience at the neural level. Both brain metrics and resilience scores can be thought of as emergent indexes influenced by a plethora of genetic, environmental, and experiential factors20. Moreover, by incorporating the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)21, the Quality of Life scale (QOL)22, and Beck's Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)23 as confounding variables in the investigation of psychological resilience is imperative as these tools collectively measure cognitive function, depressive symptoms, and overall life satisfaction, which can significantly influence individual differences in attitudes toward contradiction and thus potentially modulate the expression of psychological resilience. Our hypothesis extends to anticipate that the correlations observed in holistic and analytic cognitive processes within the framework of ZTS will manifest distinctively when compared to those of naïve dialecticism and formal logic. This is especially pertinent in an East Asian context, where cultural nuances profoundly influence cognitive styles. We expect that an Asian sample will reveal nuanced interplays between these thinking styles, offering insights into how cultural contexts can shape cognitive processing. The anticipated differences in correlations among these thinking paradigms will strengthen our understanding of the cognitive diversity shaped by cultural and philosophical doctrines. Thus, while our model proposes a directional influence from brain metrics to attitudes and subsequently to resilience, this conceptualization is a working hypothesis, open to refinement based on accumulating evidence.

Methods and results

Methods

Participants

A total of 173 right-handed individuals without any prior psychological or neurological disorders were recruited through online recruitment methods and advertisements on bulletin boards on the campus. All participants aged between 20 and 30 years old with a mean age of 22.57 ± 2.43 years (standard deviation, SD). All participants were given a written informed consent form approved by the Research Ethics Committee (No. 109–419) and Institute of Review Board (IRB, JA-109–95) of the Hospital and signed to agree to participate in this study. Prior to scanning room, all participants filled out behavioral questionnaires concerning thinking styles: AHS2 and ZTS24; Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA)19; mental health status: cognitive status (MoCA)21, quality of life (QOL)22 and depressive status (BDI-II)23 before the brain imaging scanning session. After MRI scans and questionnaires were completed, all participants received USD $80. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Measurements of mental health status

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)21 is a widely used screening tool to assess cognitive impairment. It was designed to detect mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early dementia. MoCA consists of a brief 10-min cognitive screening test that is used by healthcare professionals, such as doctors, to quickly assess cognitive impairment in patients. The test consists of a series of tasks that assess various cognitive functions such as drawing, memorization, attention, language, and abstraction. It has been shown to be more sensitive than the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)25 in detecting mild cognitive impairment and early dementia. The MoCA is generally considered especially important due to its sensitivity and specificity in detecting MCI, a condition that may precede or accompany mental health disorders, including dementia and depression26.

Beck's Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)23 is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess the severity of depression in adults and adolescents aged 13 years and older. It consists of 21 items that measure symptoms of depression, such as sadness, loss of interest in activities, changes in appetite and sleep patterns, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, and thoughts of self-harm or suicide. Scores on the BDI-II range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms of depression. The BDI-II is justified as a key instrument in mental health due to its strong psychometric properties, which include its high reliability, validity, and sensitivity to changes in depression levels over time27.

The Quality of Life scale (QOL)22 is designed to capture subjective evaluations of an individual's life satisfaction and assess their sense of fulfillment and happiness, including physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environmental factors. Participants were asked to rate their level of satisfaction on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 indicates very dissatisfied and 7 indicates very satisfied. The scale typically consists of 16 to 17 items that cover the different domains of life satisfaction. The inclusion of Quality of Life (QOL) assessments in mental health evaluations involves the subjective evaluation of both positive and negative aspects of life28.

A measure of Thinking styles (attitudes towards contradiction)

The AHS was used to assess an individual’s analytic and holistic thinking style2 (traditional Chinese version validated by)29. The AHS is a self-reported questionnaire with 24 items and four subscales (causality, attitude toward contradictions, perception of change, and locus of attention). Each item is scored on a seven-point Likert-type scale [from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree)]. In this study, we are most interested in the “attitude toward contradictions” of the subscales calculated from four items’ points. Higher scores indicate a naïve dialecticism thinking style, and lower scores indicate a more formal logical thinking style. East Asian is often described as exhibiting naïve dialecticism as a thinking strategy to tolerate contradictions, displaying lesser inclination to resolve inconsistencies1.

A measure of thinking styles (Zhongyong belief-value scales)

The ZTS24 is based on a set of belief-value scales that help individuals achieve balance, harmony, and moral integrity in their thoughts and actions. These scales include the scale of balance, the scale of harmony, the scale of integrity, and the scale of self-cultivation. Higher scores on the Zhongyong belief-value scales generally indicate that an individual is more likely to exhibit a thinking style that is balanced, harmonious, and grounded in moral integrity and self-cultivation.

A measure of psychological resilience

The Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA)19 is a self-report questionnaire that was then revised in 2006 30. We adopted a translated Chinese version of RSA; this version of RSA, consisting of 29 items, was scored using a seven-point semantic differential scale, with a higher score indicating greater resilience. The Chinese version has received great reliability of 0.89 using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and five subscales were as follows: (1) personal strength (RSA_ps), (2) family cohesion (RSA_fc), (3) social resources (RSA_sr), (4) social competence (RSA_sc), and (5) future structured style (RSA_fss).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition parameters

MRI images were acquired by a General Electronic (GE) MR750 3 T scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) at the University. High-resolution structural images with high resolution were obtained with a fast-spoiled gradient-recalled echo sequence including 166 axial slices (repetition time (TR) = 7.6 ms; echo time (TE) = 3.3 ms; flip angle = 12°; field of view (FOV) = 22.4 × 22.4 cm2; matrices = 224 × 224; slice thickness = 1 mm). The entire process lasted for 3 min 38 s. Resting-state functional images were acquired with an interleaved gradient-echo planar imaging pulse sequence (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 77, 64 × 64 matrices, FOV = 22 × 22 cm2, slice thickness = 4 mm, no gap, voxel size = 3.4375 mm × 3.4375 mm × 4 mm, 32 axial slices covering the entire brain). There were 245 volumes acquired (The protocol will discard the first five dummy scans to bring the magnetization system to a steady state). During a resting state functional scan, we instructed participants to remain awake, eyes open, and fixated on a white cross displayed on the screen, and the entire scanning time lasted for 8 min and 10 s per participant.

General procedures

Resting-state functional MRI (rfMRI)

The CONN toolbox 18a (www.nitrc.org/projects/conn) and SPM 12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) of Matlab (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) were used for the preprocessing function images. For detailed parameters and procedures, please refer to earlier studies from our group31. To identify functional networks and their properties, we employed a whole-brain parcellation template to define cortical regions of interest (ROI)32 and to compute functional connectivity between these ROIs. This template contains 400 brain area nodes, which can be further divided into Yeo’s 17 networks33 (see https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/CorticalParcellation_Yeo2011 for more detail). Network indexes were calculated for each node, including within-module-degree (WMD) and participation coefficient (PC)34. Specifically, PC can be estimated as the degree to which a node is connected to external networks, with values ranging from 0 to 1. Nodes associated solely with other nodes within a single network would have a PC of 0, while nodes with many distributed associates with many different networks would have a PC closer to 1. WMD scores of each network’s ROI were calculated using the mean and SD of the within-network degree (number of intra-network connections) calculated from each functional cortical network. Voxels within a network that have higher WMD values indicate a greater number of connections within the network. By averaging the nodes within each defined network, we extracted PC and WMD values for each network, respectively.

T1-weighted structural MRI (sMRI)

We used FreeSurfer 5.31 with an automated surface-reconstruction scheme to estimate GMVs. Regions of interest (ROIs) were extracted using neuroanatomical labels in the Desikan–Killiany Atlas to map on a cortical surface model. GMVs in each ROI of FreeSurfer’s Atlas were extracted from output aparc.stats files.

Statistical analysis

We hypothesized that cognitive thinking style measurements could be linked to levels of psychological resilience in attitudes toward contradictions. In order to test this, we calculated the AHS_contradiction score and grouped participants into two categories based on Median Split35,36 of AHS_contradiction score (for detailed distribution of AHS scores on the formal logic and naïve dialecticism, see the Supplementary file: Fig. 1–2): those with a formal logic thinking style and those with a naïve dialectism thinking style. We then employed a t-test to examine the group differences in demographic information, structural and functional brain metrics between the two groups, including RSA, MoCA, BDI, QOL, and ZTS scores. In addition to the p-value, we also report the Bayes Factor, which may be interpreted as proportional evidence for the presence or absence of an effect. When exploring the functional brain metrics (brain network) differences between the two groups, we used multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to consider all nodes within the network metrics simultaneously. Next, we analyzed the correlation between RSA and questionnaire scores, as well as the correlation with brain metrics that showed significant differences between groups while controlling for gender to minimize potential confounds. To understand the relationship between the brain, attitudes toward contradiction, and resilience, we conducted a mediation analysis to examine the indirect effect. Maximum likelihood estimation and bootstrapping methods were used to estimate the model. The significance of indirect effects was assessed with a 95% confidence interval. Bias-corrected percentile bootstrap estimation, which was used to estimate confidence intervals. 5000 bootstrap iterations were performed. A two-sided p < 0.05 was used to reject the null hypothesis if the interval did not include zero. To minimize potential confounds, statistical analysis was first to ensure all participants’ mental health status of demographic information (e.g., MoCA and BDI-II) was identical between groups of contradictory attitudes and even controlled for possible gender effects throughout the entire statistical testing. These strategies help increase the power of this study, which is essential for detecting true effects and reducing the likelihood of false positives. All analyses were conducted using statistical modeling programs SPSS version 22.0., Chicago, IL, USA, network visualization package version 1.4.99.9004 (https://r.igraph.org/) with R37 and JASP version 0.1538. Mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro v3.1 developed by Hayes and colleagues39,40.

Transparency and openness

In accordance with Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS)41, we provide details on how we arrived at our sample size, as well as any data exclusions, manipulations, and measures used in our study. All analyses were conducted using statistical modeling programs SPSS version 22.0., Chicago, IL, USA, and JASP version 0.1538 and network visualization package version 1.4.99.9004 (https://r.igraph.org/) with R37. Moreover, we did not pre-register the analysis or design of this study. An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power version 3.1.9.442 to determine the minimum sample size required to test the study hypothesis. Results indicated the required sample size to achieve 80% power for detecting a medium effect, at a significance criterion of α = 0.05 (two-tailed), was a total sample size of N = 128 for the t-test and a total sample size of N = 94 for MANOVA.

Ethics approval

All participants were given a written informed consent and signed to agree to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (No. 109–419) and Institute of Review Board (IRB, JA-109-95) of Hospital.

Results

Demographic information

Participants with formal logic (mean scores = 25.41 ± 4.01) were compared to those with naïve dialecticism (mean score = 34.43 ± 2.41) based on attitude towards contradiction scores showed significant group differences on RSA_fc (t(171) = 4.334, p < 0.001), RSA_total(t(171) = 2.687, p < 0.01), QOL_soc (t(171) = − 2.569, p < 0.05), and ZTS (t(171) = − 4.703, p < 0.001). On the other hand, demographic measures (i.e., MoCA, BDI-II, QOL_Phy, QOL_Psy, QOL_Env) showed no statistical differences between formal logic and naive dialecticism groups. All results are reported in Table 1.

Group differences between brain metrics: t-test and MANOVA

Between groups from different attitudes were compared, their structural brain metrics in both hemispheres showed significant differences in rostral parts of the inferior frontal gyrus (i.e., Pars Orbitalis in the left (t(171) = 3.920, p < 0.001, BF10 = 166.545) and in the right hemisphere (t(171) = 2.317, p < 0.05, BF10 = 1.942)), Inferior Parietal in the right hemisphere (t(171) = 2.162, p < 0.05, BF10 = 1.416), Middle Temporal in the right hemisphere (t(171) = 2.065, p < 0.05, BF10 = 1.175), Pars Opercularis in the right hemisphere (t(171) = 2.104, p < 0.05, BF10 = 1.264), Precentral in the right hemisphere (t(171) = 2.725, p < 0.01, BF10 = 4.925) and Precuneus in the right hemisphere (t(171) = 2.461, p < 0.05, BF10 = 2.656). Results are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

MANOVA analysis was used to examine between-group comparison on functional brain metrics in both hemispheres, showing significant differences in WMD of the central visual network (F(24, 148) = 1.710, Pillais’ Trace = 0.217, p < 0.05), PC of dorsal attention B (F(25, 147) = 1.710, Pillais’ Trace = 0.224, p < 0.05), WMD of salience/ventral attention A (F(34, 138) = 2.029, Pillais’ Trace = 0.333, p < 0.01), and WMD of control C network (F(12, 160) = 1.927, Pillais’ Trace = 0.129, p < 0.05). Results are reported in Supplementary Table 2. Significant between-group differences in brain metrics are summarized in Fig. 1.

Correlation between resilience measures and demographic information by group: pearson’s coefficients

Correlation analysis was performed to explore the relationship underlying behavioral measures. Results are plotted in Fig. 2 and reported in Supplementary Table 3. A significant negative correlation between total resilience scores with BDI-II was observed in formal logic (Pearson’s r = − 0.547; p < 0.001) and naïve dialecticism (Pearson’s r = − 0.419; p < 0.001). Moreover, a significant positive correlation between AHS_contradiction and Zhongyong scores (Pearson’s r = 0.360; p < 0.001) across groups was observed. Similarly, we also observed a significant positive correlation between RSA_sr and QOL_soc in both groups (formal logic: Pearson’s r = 0.634; p < 0.001; naïve dialecticism: Pearson’s r = 0.510; p < 0.001).

Correlation (Pearson’s r value) between resilience measures and demographic variables by group. RSA: Resilience Scale for Adults (ps: personal strength; fc: family cohesion, sr: social resource, sc: social competence, fss: future structured style), MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment, BDI-II: Beck’s Depression Inventory-II. Blue lines represent a negative correlation, while red lines represent a positive correlation, Zhongyong: Zhongyong thinking styles.

Correlations between resilience measures and brain metrics by group: Pearson’s coefficients

Correlation analysis explored the relationship between behavioral measures and brain metrics. For the formal logic group, significant positive correlations between brain metrics of dorsal attention networks and subscales of resilience score were observed. Specifically, positive correlations of DorAttB_WMD with RSA_fc (Pearson’s r = 0.222; p < 0.01), RSA_sr (Pearson’s r = 0.161; p < 0.05), RSA_sc (Pearson’s r = 0.155; p < 0.05), and RSA_total (Pearson’s r = 0.214; p < 0.01) were observed, whereas a negative correlation between RSA_sc and parORB_L (Pearson’s r = − 0.250; p < 0.05) was also observed. For the naïve dialecticism group, a positive correlation between parOPC_R and RSA_fc was found (Pearson’s r = 0.209; p < 0.05), while a negative correlation between parOPC_R and RSA_sc was observed (Pearson’s r = − 0.223; p < 0.05). Results were plotted in Fig. 3 and reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Correlations between resilience measures and brain metrics by group. RSA: Resilience Scale for Adults (ps: personal strength; fc:family cohesion; sr: social resource; sc: social competence; fss: future structured style); parORB: Pars Orbitalis; infP: Inferior Parietal; midT: Middle Temporal; parOPC: Pars Opercularis; DorAtt: dorsal attention; CenVisu: central visual; SaVenAtt: Salience/Ventral Attention; WMD: Within module degree; PC: participation coefficient; Blue lines represent negative correlation, while red lines represent positive correlation.

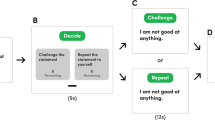

Mediation

To further examine our hypothesis on the role of conflicting resolution in determining psychological resilience, we tested a parallel mediation model on attitudes towards contradictions across groups mediating the relationship between structural and functional brain matrices and resilience scores. The mediation model is visualized in Fig. 4. Mediation analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of attitudes toward contradictions on the links between brain metrics and psychological resilience. Specifically, the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval based on 5000 bootstrap samples revealed a significant specific indirect effect of LH_parORB, R_precentral, and R_precuneus in structural brain metrics on the resilience measure through AHS_contradiction as a mediator. Similarly, in functional brain metrics, controlC_PC showed a significant specific indirect effect on the resilience measure through AHS_contradiction as a mediator. All results were reported in Supplementary Table 5.

General discussion

We investigated whether attitudes towards contradictions, as gauged by the AHS, facilitate resilience amid life's challenges by influencing the management and resolution of conflicts, a relationship that may be reflected in brain network patterns. The subscales used within the AHS to assess attitudes toward contradictions revealed discernible differences between the two thinking styles in question—formal logic and naïve dialecticism. Our findings indicated that scores related to naïve dialecticism are not only significantly higher but also exhibit a smaller standard deviation compared to those of formal logic. This pattern suggested a greater consistency among Asian participants who align with naïve dialecticism, implying that this cognitive style may be measured with greater reliability within our sample. Furthermore, our observations indicate a distinctive pattern: a significant and unique correlation exists between the dialectical thinking style, as measured by the AHS, and the Zhongyong thinking style, as denoted by the ZTS. This correlation aligns with the central hypothesis that the cognitive style characterized by an acceptance of complexity and a synthesis of varied perspectives—hallmarks of naïve dialecticism—correlates strongly with Zhongyong's holistic approach. These observations suggested that the differences in the attitude toward contradiction in levels of psychological resilience, indicating the possible role of attitudes towards contradictions (i.e., formal logic and naïve dialecticism) on the appraisal of the situation, may be related to resilience measures in the face of life's challenges and difficulties. To support this notion, we further examined the attitude toward contradiction differences in structural and functional MRI properties associated with brain cortices involved in conflict resolution. The group differences in structural and functional brain cortices, such as the inferior frontal area, parietal and anterior cingulate cortex, were commonly thought of as parts of brain networks for conflicting resolution. Structurally asymmetric between-group differences of brain volumetrics in these brain regions indicate right-hemispheric lateralization in different attitudes towards contradictions within cortical networks connectivity in dorsal attention network positively associated with psychological resilience estimates at the individual level, suggesting possible links of top-down conflict resolution process in psychological resilience. Mediation results highlighted that individuals with stronger attitudes toward resolving contradictions might have more psychological resilience. These attitudes toward contradictions may help individuals regulate the impact of conflicting information on their emotions and cognition, leading to better mental health and quality of life. The results also highlight the importance of frontoparietal brain networks for executive control in resolving conflicting information and regulating the impact of contradictions on psychological resilience. Our findings suggest a potential role of cortical conflicting resolution networks in attitudes towards contradictions and psychological resilience.

One's general perceptions and misperceptions of a challenging situation would lead to entirely different coping strategies for stressor events. Indeed, our findings observed that the differences in the attitude toward contradiction modulated levels of psychological resilience, indicating the possible role of thinking styles in the appraisal of the situation may be related to resilience estimates in facing life's challenges and difficulties. These observations suggested the potential role of attitudes towards contradictions as coping strategies in facing life difficulties or conflict situations. A previous patient study43 with lower extremity amputation reported that positive meaning aspects, such as improved attitudes towards life and independence, were noted in 49% of the 104 patients. They also found that positive meaning about amputation was linked to higher ratings of physical capabilities, better adjustment to physical limitations, and lower activity restriction. As such, thinking style does appear to be a key determinant of long-term adjustment to amputation and related face-of-life adversities. The ability to switch ways of thinking about how they perceive and interpret adverse events in their immediate and future lives43. For example, a child might see an obstacle as an insurmountable barrier or a transient challenge that offers a unique opportunity for learning, growth, and aptitude. When children have higher self-efficacy and a more vital internal locus of control, they are more likely to exhibit adaptive behaviors and attitudes that can lead to resilience in various areas of development44,45. These findings support our view44 of perception or cognitive appraisal of the situations about their later adaption into everyday life. According to a previous review, coping strategies often distinguish between confronting conflicts head-on and those that aim to reduce tension by avoiding confrontation with the conflict. Likewise, a recent large-scale study46 investigated brain structural correlates of parent–child relationships in eight thousand children. Their findings reported that high family conflict and low parental monitoring scores are associated with children’s behavioral problems and smaller cortical areas of the inferior frontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and middle temporal gyrus. In our study, we observed the thinking style differences in structural and functional MRI properties associated with brain cortices involved in conflict resolution47,48,49, supporting our notion of the role of conflict resolution in the face of life difficulties or adversities.

In anticipation, our hypothesis posited that Zhongyong's holistic tendencies would differ in their correlation with naïve dialecticism versus formal logic. The data from our East Asian sample indeed reveal this to be the case, underscoring the cultural specificity of cognitive processes. The clarity of these correlations not only supports our initial hypothesis but also enriches the broader dialogue on how cognitive diversity, shaped by deep-seated cultural and philosophical beliefs, manifests in the ability to withstand and adapt to life's adversities. The ZTS4, derived from the core Confucian principle of pursuing balance and harmony, inherently involves a holistic consideration of multiple perspectives. Such a holistic tendency shares common ground with naïve dialecticism, a cognitive style characterized by a tolerance for contradiction and a propensity for seeking synthesis among opposing views. This investigation into the cognitive styles of East Asian populations reinforces the notion that a dialectical perspective, which emphasizes finding a middle way and favors balancing conflicting viewpoints50, may be inherently linked to resilience. In this context, incorporating the ZTS was to establish a foundational reference for our East Asian sample set. Thus, our research elucidates the multifaceted nature of cognitive approaches in navigating life’s adversities and their implications for psychological resilience.

Despite the fruitful findings above, this study found noteworthy variations in the social support scale of the QOL22 between attitudes toward contradictions, with Naïve Dialecticism exhibiting a correlation with higher social support levels. Consistent with this observation, the connection between the attitudes towards contradictory subscales of cognitive thinking style measurements and levels of psychological resilience was already established in this study. Prior studies have indicated that social support is a powerful predictor of psychological resilience51,52. The current study speculates that these different attitudes towards contradictions can lead to differences in social connections, which can ultimately impact psychological resilience. Together with prior studies53, we deem that Naïve Dialecticism was related to stronger social connections, which could clarify why it is linked to greater psychological resilience. Naïve Dialecticism accentuates the importance of contextual factors, which could help individuals to build stronger social connections and support networks. On the other hand, the Formal Logical thinking style may be less effective in forming these connections, as it prioritizes rules and principles. These findings suggest that distinct attitudes towards contradictions could influence an individual's psychological resilience by affecting their social connections. It underscores the significance of considering cultural and contextual factors when examining these complex concepts. It also implies that Naïve Dialecticism could be crucial in building strong social connections and promoting psychological resilience.

In this study, Control-A, -B, and -C resemble subnetworks of the frontoparietal brain regions. These brain regions and networks are key for executive control of cognition and emotion in conflicting task-irrelevant information. The frontoparietal spans frontal, parietal, and cingulate brain regions associated with executive functions54,55. These regions formed as brain networks subserve conflicting resolution and encompass across brain regions, including the inferior frontal cortex (IFC), superior parietal cortex (SPC), superior occipital cortex (SOC), and right anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)47,48,49. Structurally asymmetric between-group differences with different attitudes towards contradictions of brain volumetrics in these brain regions indicate right-hemispheric lateralization in right-handed healthy young adults. According to Roger's hypothesis56, in right-handers, the right hemisphere is responsible for maintaining stability and reacting quickly to unexpected stimuli from both the external and internal environment. On the other hand, the left hemisphere is responsible for predicting future events and maintaining precise and efficient movements in predictable situations. Specifically, from a motor control perspective, the right hemisphere is specialized in using impedance control mechanisms to maintain stable positions and velocities in the face of unpredictable events and to ensure accuracy and stability in steady-state postures57. However, a modified version of the hemispheric lateralization hypothesis58 suggests that the right hemisphere is primarily responsible for emotion-related processes, while the left hemisphere plays a lesser role. This revised view argues that the right hemisphere is naturally biased toward emotional perception59. Interestingly, according to the approach-withdrawal hypothesis60, the right hemisphere, particularly the frontal lobe, is activated in response to emotions that elicit avoidance behavior. The left hemisphere is activated in response to emotions that encourage approach behavior. In sum, this hypothesis on right-hemispheric lateralization in right-handers could be speculated as emotional-related behavior, especially in avoidance behavior. Our findings indicate attitudes towards contradictions differences in brain structural and functional brain cortices in relation to conflict resolution networks may contribute to avoidance behavior in conflicting or difficult situations in life.

Regarding functional brain dynamics, we observed cortical network connectivity in the dorsal attention network positively associated with psychological resilience measures at the individual level, suggesting possible links to the top-down conflict resolution process in psychological resilience. The dorsal attention network comprises frontal and parietal regions involved in goal-directed processing related to visual attention61. Specifically, the dorsal attention network includes the frontal eye fields, superior parietal lobule, and intraparietal sulcus33,61,62. The critical brain regions within the dorsal attention network are also spanned over the brain regions related to processing conflict resolution47,48,49 such as IFC, SPC, SOC, and right ACC. A previous study63 examined the influence of emotion on executive control by examining the flanker conflict effect (incongruent-congruent) with emotional and neutral word stimuli. The findings revealed that the ventral ACC responds to cognitive conflict, as indicated by using stimuli with different colors, but only in the presence of emotional stimuli with negative valence. The combination of reduced reaction time in the conflict condition and increased activation in the ventral ACC suggests that emotion may substantially impact conflict resolution more than conflict monitoring. In line with our previous discussion on right hemisphere lateralization in brain structural and functional cortices, a recent study64 has shown the right-hemisphere superiority of this dorsal attention network. Our study found that thinking style differences in the shared brain structural and functional brain cortices are associated with levels of psychological resilience, especially in conflict resolution for the cognitive control of emotions.

There are some uncertainties and limitations that should be considered. Firstly, this study’s sample consisted of only healthy young adults, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations, age groups, and settings. We recognize that our study might be limited by the sample size and the estimation of effect size. The absence of large-scale datasets in this specific research area poses a challenge to achieving the ideal statistical power. Future studies could address this limitation by recruiting a more diverse sample to improve the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for causal inferences, and longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the relationship between attitudes toward contradictions and psychological resilience. Thirdly, using self-reported measures for cognitive thinking styles and psychological resilience may be subject to bias and may not accurately reflect actual cognitive processes or resilience in real-life situations. Specifically, we acknowledge the limitations in operationalizing psychological resilience primarily through self-report questionnaires. Kalisch et al. (2017) suggested that resilience is best measured by tracking individuals' functioning levels after exposure to life adversities65, which our current study design does not encompass. Kalisch and colleagues argue that resilience is best understood by examining variations in markers and competencies post-adversity, emphasizing the importance of situational processes in resilient performance65,66. This approach aligns with the conceptualization of resilience as not only the maintenance but also the rapid recovery of mental health and psychosocial functioning during and after times of adversity65,66,67. Acknowledging these perspectives, our study could benefit from integrating measures that capture these dynamic changes, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of psychological resilience. Accordingly, future research could benefit from employing longitudinal designs that track individuals' mental health trajectories over time, post-adversity. Lastly, this study's reliance on self-report measures and the use of a median split to categorize participants may affect the reproducibility of the results, primarily since this study's limitations surrounding the dichotomy of East–West cultural thinking styles in East Asian societies must be acknowledged. Nonetheless, examining these differences within the context of East Asia alone diminishes the potential for cultural biases and assumptions, providing a more nuanced and culturally specific understanding of the biases and attitudes towards the conflict in these societies.

Conclusion

Together, our findings contributed to cumulative theoretical knowledge in social psychology, social cognition, and attitudes by exploring the relationship between attitudes toward contradictions, conflict resolution-related cortical brain networks, and psychological resilience at the neural level using structural and functional MRI in different attitudes toward contradiction groups. We built on and extended commonly accepted theoretical frameworks in attitudes and social cognition by examining the role of cortical conflict resolution networks between attitudes towards contradictions and psychological resilience. It also challenged these frameworks by suggesting potential links between conflict resolution and psychological resilience in the frontoparietal network. These findings support the hypothesis that cognitive thinking style measurements could be linked to levels of psychological resilience in attitudes toward contradictions. The differences in the attitude toward contradiction in levels of psychological resilience suggested the possible role of thinking styles in the appraisal of the situation, which is also in line with our conceptual model of psychological resilience68.

We highlighted executive control's importance in regulating contradictions' influence on psychological resilience, emphasizing the need to recognize realistic obstacles to a successful resolution. We also suggested the potential role of thinking styles as coping strategies in facing life difficulties or conflict situations and highlighted the importance of contextual factors in building stronger social connections and support networks. In sum, we provide valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying the relationship between attitude towards contradictions, conflict resolution-related cortical brain networks, and psychological resilience. Regarding the implications, our findings can be helpful in developing interventions to help individuals deal with adversity and develop resilience by focusing on cognitive thinking styles and conflict resolution strategies.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Peng, K. & Nisbett, R. E. Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. Am. Psychol. 54, 741–754 (1999).

Choi, I., Koo, M. & Choi, J. A. Individual differences in analytic versus holistic thinking. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 33, 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720629856833,691-705 (2007).

Santos, D., Requero, B. & Martín-Fernández, M. Individual differences in thinking style and dealing with contradiction: The mediating role of mixed emotions. PLoS ONE 16, e0257864 (2021).

Zhou, S. & Li, X. Zhongyong thinking style and resilience capacity in chinese undergraduates: The chain mediating role of cognitive reappraisal and positive affect. Front. Psychol. 13, 814039 (2022).

Miyamoto, Y. & Ryff, C. D. Cultural differences in the dialectical and non-dialectical emotional styles and their implications for health. Cogn. Emot. 25, 22 (2011).

Spencer-Rodgers, J., Boucher, H. C., Mori, S. C., Wang, L. & Peng, K. The dialectical self-concept: Contradiction, change, and holism in East Asian cultures. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35, 29–44 (2009).

Meng, L., Huang, J., Qiu, C., Liu, Y. & Niu, J. The structural relations of dispositional mindfulness, Zhongyong, resilience, and subjective well-being among Chinese high school students. Curr. Psychol. 1, 1–13 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Confucian culture still matters: The benefits of Zhongyong thinking (doctrine of the mean) for mental health. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 47, 1097–1113 (2016).

Franklin, T. B., Saab, B. J. & Mansuy, I. M. Neural mechanisms of stress resilience and vulnerability. Neuron 75, 747–761 (2012).

Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., Bisconti, T. L. & Wallace, K. A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 730–749 (2006).

Tugade, M. M. & Fredrickson, B. L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 86, 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320 (2004).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. Conflict resolution: A cognitive perspective. in Choices, Values, and Frames 473–488 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803475.027.

Egner, T. & Hirsch, J. Cognitive control mechanisms resolve conflict through cortical amplification of task-relevant information. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1784–1790 (2005).

Dixon, M. L. et al. Heterogeneity within the frontoparietal control network and its relationship to the default and dorsal attention networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E1598–E1607 (2018).

Hsu, H. M., Yao, Z. F., Hwang, K. & Hsieh, S. Between-module functional connectivity of the salient ventral attention network and dorsal attention network is associated with motor inhibition. PLoS One 15, e0242985 (2020).

Ptak, R. The frontoparietal attention network of the human brain: Action, saliency, and a priority map of the environment. Neuroscientist 18, 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858411409051 (2012).

Davidson, R. J. & Mcewen, B. S. Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 689 (2012).

Kim, M. J. & Whalen, P. J. The structural integrity of an amygdala-prefrontal pathway predicts trait anxiety. J. Neurosci. 29, 11614–11618 (2009).

Friborg, O., Hjemdal, O., Rosenvinge, J. H. & Martinussen, M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: What are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment?. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 12, 65–76 (2003).

Davies, G. et al. Genetic contributions to variation in general cognitive function: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in the CHARGE consortium (N = 53 949). Mol. Psychiatry 20(2), 183–192 (2015).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Yang, S. C., Kuo, P. W., Wang, J. D., Lin, M. I. & Su, S. Development and pyschometric properties of the dialysis module of the WHOQOL-BREF Taiwan version. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 105, 299–309 (2006).

Steer, R. A., Ball, R., Ranieri, W. F. & Beck, A. T. Dimensions of the beck depression inventory-II in clinically depressed outpatients. J. Clin. Psychol. 55, 117–128 (1999).

Wu, J. H. & Lin, Y. Z. Development of a Zhong-yong thinking style scale. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 24, 247–300 (2005).

Hoops, S. et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 73, 1738–1745 (2009).

Luis, C. A., Keegan, A. P. & Mullan, M. Cross validation of the montreal cognitive assessment in community dwelling older adults residing in the southeastern US. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 24, 197–201 (2009).

Dozois, D. J. A., Dobson, K. S. & Ahnberg, J. L. A psychometric evaluation of the beck depression inventory-II. Psychol. Assess 10, 83–89 (1998).

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M. & O’Connell, K. A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual. Life Res. 13, 299–310 (2004).

Jen, C. H. & Lien, Y. W. What is the source of cultural differences?—examining the influence of thinking style on the attribution process. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 133, 154–162 (2010).

Friborg, O. et al. Resilience as a moderator of pain and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 61, 213–219 (2006).

Hsieh, S., Yao, Z. F. & Yang, M. H. Multimodal imaging analysis reveals frontal-associated networks in relation to individual resilience strength. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–19 (2021).

Schaefer, A. et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cerebral Cortex 28, 3095–3114 (2018).

Thomas Yeo, B. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

Guimerà, R. & Amaral, L. A. N. Cartography of complex networks: Modules and universal roles. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2005/02/P02001 (2005).

Iacobucci, D., Posavac, S. S., Kardes, F. R., Schneider, M. J. & Popovich, D. L. The median split: Robust, refined, and revived. J. Consumer Psychol. 25, 690–704 (2015).

Allen, M. The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. SAGE Encyclopedia Commun. Res. Methods https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483381411 (2017).

R Team, R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Found. Stat. Comput., 10, 11–18 (2020).

JASP Team. JASP. [Computer software] Preprint at https://jasp-stats.org (2022).

Hayes, A. F. Beyond baron and kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420 (2009).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891 (2008).

Kazak, A. E. Editorial: Journal article reporting standards. Am. Psychologist 73, 1–2 (2018).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Gallagher, P. & MacLachlan, M. Positive meaning in amputation and thoughts about the amputated limb. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 24, 196–204 (2000).

Kennedy, P., Lude, P., Elfstrm, M. L. & Smithson, E. F. Psychological contributions to functional independence: A longitudinal investigation of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 92, 597–602 (2011).

Bonanno, G. A. Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: Loss, trauma, and health-related adversities. Soc. Sci. Med. 74, 753–756 (2012).

Gong, W., Rolls, E. T., Du, J., Feng, J. & Cheng, W. Brain structure is linked to the association between family environment and behavioral problems in children in the ABCD study. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–10 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Conflict detection and resolution rely on a combination of common and distinct cognitive control networks. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 83, 123–131 (2017).

Matsumoto, K. & Tanaka, K. Conflict and cognitive control. Science 1979(303), 969–970 (2004).

Botvinick, M. M., Carter, C. S., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M. & Cohen, J. D. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol. Rev. 108, 624–652 (2001).

Ji, L. J., Nisbett, R. E. & Su, Y. Culture, and prediction. Psychol. Sci. 12, 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00384 (2001).

Ozbay, F. et al. Social support and resilience to stress: From neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 4, 35–40 (2007).

Southwick, S. M. et al. Why are some individuals more resilient than others: The role of social support. World Psychiatry 15, 77–79 (2016).

Spencer-Rodgers, J., Williams, M. J. & Peng, K. Cultural differences in expectations of change and tolerance for contradiction: A decade of empirical research. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 14, 296–312 (2010).

Yao, Z. F., Yang, M. H., Hwang, K. & Hsieh, S. Frontoparietal structural properties mediate adult life span differences in executive function. Sci. Rep. 10, 66083 (2020).

Smith, S. M. et al. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13040–13045 (2009).

Rogers, L. J., Zucca, P. & Vallortigara, G. Advantages of having a lateralized brain. Proc. Royal Soc. B Biol. Sci. 271, S420 (2004).

Sainburg, R. L. Convergent models of handedness and brain lateralization. Front. Psychol. 5, 1092 (2014).

Demaree, H. A., Everhart, D. E., Youngstrom, E. A. & Harrison, D. W. Brain lateralization of emotional processing: Historical roots and a future incorporating ‘dominance’. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 4, 3–20 (2005).

Stanković, M. A conceptual critique of brain lateralization models in emotional face perception: Toward a hemispheric functional-equivalence (HFE) model. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 160, 57–70 (2021).

Davidson, R. J., Ekman, P., Saron, C. D., Senulis, J. A. & Friesen, W. V. Approach-withdrawal and cerebral asymmetry: Emotional expression and brain physiology I. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 330–341 (1990).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 (2002).

Osher, D. E., Brissenden, J. A. & Somers, D. C. Predicting an individual’s dorsal attention network activity from functional connectivity fingerprints. J. Neurophysiol. 122, 232–240 (2019).

Kanske, P. & Kotz, S. A. Emotion triggers executive attention: Anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala responses to emotional words in a conflict task. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 198–208 (2011).

Spagna, A., Kim, T. H., Wu, T. & Fan, J. Right hemisphere superiority for executive control of attention. Cortex 122, 263–276 (2020).

Kalisch, R. et al. The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nat. Human Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0200-8 (2017).

Jones, L. B., Kiel, E. J., Luebbe, A. M. & Hay, M. C. Resilience in mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Family Psychol. 36, 815–826 (2022).

Bonanno, G. A., Romero, S. A. & Klein, S. I. The temporal elements of psychological resilience: An integrative framework for the study of individuals, families, and communities. Psychol. Inq. 26, 139–169 (2015).

Yao, Z.-F. & Hsieh, S. Neurocognitive mechanism of human resilience: A conceptual framework and empirical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 5123 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Mind Research and Imaging Center (MRIC) at National Cheng Kung University for consultation and the instrument's availability.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (ROC) of the Republic of China, Taiwan, for financially supporting this research (Grant Number Nos. 108-2410-H-006-038-MY3, 108-2321-B-006-022-MY2, 109-2923-H-006-002-MY3, 110-2321-B-006-004, 111-2321-B-006-008, 111-2410-H-006-114, and 112-2321-B-006-013). In addition, this research was partly supported by the Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU) (Grant Number: D111–F2903; D111-F2909; R111-B013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.F.Y.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. M.H.Y.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—review, and editing. C.T.Y.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing—review, and editing. Y.H.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing—review, and editing. S.H.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision, Writing—review, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, ZF., Yang, MH., Yang, CT. et al. The role of attitudes towards contradiction in psychological resilience: the cortical mechanism of conflicting resolution networks. Sci Rep 14, 1669 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51722-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51722-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.