Abstract

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment accounted for 6% of total births in 2017 and is increasing which places Japan among the top worldwide in number of treatments performed. Although ART treatment patients often experience heavy physical and psychological burden, few epidemiologic studies have been conducted in Japan. We examined mental health and health-related quality of life (QOL) among women at early stages of treatment. We recruited 513 women who have initiated ART treatment, either in-vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection, from four medical facilities in the Tokyo area and through web-based approaches. At baseline, we collected socio-demographic information and assessed depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL. Descriptive analyses were performed overall and stratified by factors such as age. Mild depressive symptoms or worse, assessed with Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, were observed among 54% of participants. Mean score for State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was 52 with a standard deviation of 11 for the state, and 39% were categorized as high anxiety. QOL results, assessed with SF-12, showed the same negative tendency for social functioning and role (emotional), while general health and physical functioning were consistent with the national average. Young participants appeared to suffer mentally more than older participants (p < 0.01 for depressive symptoms). Our findings suggest that patients may be at high risk of depressive symptoms, high anxiety, and low QOL even from the early stages of ART treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The low fertility trend has continued over a half century in Japan, and the total births per year have drastically declined, from 2.09 million in 1975 to 0.86 million in 20191. By contrast, the number of births by assisted reproductive technology (ART), such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), have increased steadily during the past 20 years from 12,274 in 2000 to 56,617 in 2017, currently accounting for about 6% of total births per year in Japan2. In 2017, about 450,000 treatments were performed, placing Japan at the top worldwide in terms of utilization frequency. Delayed childbearing among Japanese couples is likely to be a main driver for the increase, but the prevalence of infertility, defined as not becoming pregnant after 1 year of unprotected sexual intercourse on a regular basis, remains unknown in Japan due to absence of epidemiological studies.

Medical cost of ART treatment is often very high3,4, in which treatment over one cycle costs between 300,000 and 500,000 Yen (approximately 3000–5000 US dollars) or more in Japan according to a 2018 survey5. This is an out of pocket expense because medical insurance is not applicable to ART in Japan. Government financial assistance has been available and expanded from 2021, removing household income threshold in response to high demands. Despite the high cost of ART treatment, the reality is that having a child still may not be the outcome: 16% (3555 births/21,939 embryo transfers) success with conventional IVF and 24% (46,396 births/194,415 embryo transfers) success with frozen embryo transfer according to 2017 national data2.

In addition to the high cost, ART treatment is known to place heavy burden on physical and mental health, particularly in women6,7,8. In other developed countries, infertility treatment is also on the rise, and numerous epidemiologic studies have examined the negative impact of infertility treatment on mental health and health-related quality of life (QOL). These studies showed that treatment is often associated with high levels of stress and distress and lower QOL among the patients9,10,11. Also, studies have shown that the stress from the treatment may be associated with discontinuation of treatment12,13,14. However, it is still inconclusive whether there is a relationship between stress levels and achieving pregnancy15,16,17.

Despite Japan being number one in the world in terms of number of ART treatments, epidemiologic studies investigating physical and mental health of patients undergoing infertility treatment remain scarce. To our knowledge, there are only three studies published in international journals18,19,20, and no studies have exclusively focused on ART patients. To address this gap, we have initiated a prospective cohort study of women receiving ART treatments; in this report, we introduce the design and methodological features of this ongoing study, and describe the depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL, as well as socio-demographic characteristics of women who are in early stages of ART treatment.

Method

Study population and recruitment

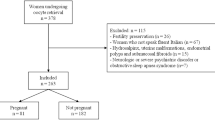

Women at early stages of ART treatment were enrolled into our cohort study. The eligibility to participate in this study included patients who were either, (1) starting the ART treatment (IVF or ICSI) with no prior experiences, or (2) had started the treatment and retrieved oocytes once or twice at the time of recruitment. We employed two methods of recruitment for this study, one of which was through clinicians at medical facilities. Participants were recruited at four medical facilities in Tokyo and Kanagawa prefectures, which offer infertility treatment. The clinicians distributed a study envelope that consisted of a description of the study, consent form, and baseline survey to eligible patients at the initial counseling session. Those willing to participate filled out the consent form and survey and returned them using an enclosed envelop with the return address and postage. A total of 74 participants were recruited from the medical facilities. The second approach to recruitment comprised the use of a study website which was advertised through social networking services and media-related outlets. Those who visited the website and had interest in participating registered their mailing address, and a study envelope was mailed to them. A total of 439 from 550 registrations participated (80% participation rate). We included those with children as long as they had no experience with ART in prior pregnancies and excluded those who were already pregnant as a result of treatment. The total number of participants was 513, and informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from each participant. Reported content followed the STROBE checklist for cohort studies. This study was performed in accordance with the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, and an approval from ethics committee for this study was obtained at the National Center for Child Health and Development (No. 1993).

Follow-up

Participants are followed for 1 year during which time a series of six questionnaires are administered sequentially every 2 months in order to evaluate the trajectories of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL as multiple cycles of ART treatment are pursued (i.e., oocyte retrievals and embryo transfers). The number of oocyte retrievals and embryo transfers were ascertained at the baseline survey and at follow-up. Participants are followed up to 1 year or until time of withdrawal or loss to follow-up, and are censored at the point of achieving pregnancy.

Main outcomes

The main interests of this study are depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL among women who begin ART treatment. We used QIDS (the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self report) to assess depressive symptoms, STAI (the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) to assess anxiety, and SF-12 to assess QOL. Using the total score for QIDS, we created a five-category variable21: none, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe. Using the total scores for state and trait, each was categorized into 5 levels where 1 represented the lowest anxiety level and 5 was the highest; we defined categories 4 and 5 as high anxiety22. Based on the SF-12 responses, scores for 8 sub-scales were calculated: physical functioning, role (physical), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role (emotional), and mental health. The raw scores were transformed into norm-based scores with the average of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, in which lower scores indicated signs of low QOL23.

Socio-demographic variables

We collected a range of socio-demographic information: age, educational attainment, employment status such as type of employment and company size, residing prefecture, and income of the women/patients and their partners. Type of employment was grouped into three categories: full-time, part-time, and not working. Part-time included those who worked part-time, were contractual, or self-employed. Not working included unemployed, housewife, and student. Education was classified into three levels: high school graduate or below; vocational school or 2-year college; and 4-year college or graduate school. We also obtained information on height and weight to calculate body mass index, durations for marriage and infertility treatment (e.g., intrauterine insemination), reasons for wanting a child, sources of emotional support, a sub-scale for partner relationship24, and method of financing for the treatment. We inquired about the age and sex of children if there were any and the method of their conception (i.e., naturally conceived or not).

Despite the increasing popularity of ART treatment, characteristics of patients remain unknown. To further understand socio-demographic characteristics of ART patients in relation to the general population, we utilized 2016 data from the Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions, comprising a nationally representative sample of Japanese families conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, for comparison25. From the national data, we extracted married women between the ages of 20 and 45 who do not have children (n = 7468).

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive analysis to examine the proportions across categories of QIDS and STAI and average scores for the SF-12 sub-scales among the participants. Additionally, we stratified QIDS and STAI categories and SF-12 sub-scales by number of oocyte retrievals, number of children, and age categories and assessed whether or not the pattern of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL varied by these factors using chi-square tests and simple linear regression. We treated number of oocyte retrievals and age categories as ordinal in the simple linear regression analysis. A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analysis was done with STATA 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In Table 1, we present socio-demographic information of study participants and of women sampled from a nationally-representative survey of the general population (married women with no children). Compared to the general population, we observed a larger proportion of women in their 30 s in this study where the mean age was 35 years (range 24–46 years). The proportion of full-time employment and working at larger companies was higher in this study than the general population (full-time employment: 48% vs. 37%; working at a company with ≥ 1000 employees: 27% vs. 19%), as was the proportion of highly educated women (65% vs. 27%). Participants were mainly from Tokyo and neighboring prefectures. Although income information was not available for the general population, we expect that study participants likely had higher earnings. Half of the participants noted that the reason for infertility was unknown. There were 28 participants (5%) who had 3 or more experiences with oocyte retrieval at baseline. Although they were not eligible to participate in this study, we retained them for comparison purposes.

In Table 2, we present levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL among the participants. The mean score for the QIDS was 7.0 (SD 4.7), and the state and trait scores for the anxiety scale were 51.7 (SD 11.3) and 52.8 (SD 11.4), respectively. Categorization of the QIDS score showed that 54% of participants were already showing some signs of depressive symptoms. Anxiety also seemed to be high among the participants (39% for categories 4 and 5 for state). We also observed similar patterns with the QOL sub-scale scores. Norm-based scores showed that social functioning, role (emotional), and mental health aspects were low in particular, while physical functioning and general health were near the average.

In Table 3, we present depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL stratified by number of oocyte retrievals, number of children, and age categories. We did not observe a clear pattern with the exception of physical role functioning appearing lower among those with more oocyte retrievals. We observed those with one or more children seemed to be doing better mentally. Young participants (i.e., < 30.0) seemed to show higher prevalence of depressive symptoms and higher anxiety and lower QOL scores than older participants.

Discussion

In this report, we described the profile of a new longitudinal study aimed at addressing gaps in the current epidemiological literature on the mental health and well-being of women undergoing ART treatment in Japan. We provided a first report focused on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL as well as socio-demographic profiles of women who were starting or had just started ART treatments. Results showed that indicators of mental health already appeared unfavorable at the early stages of ART treatment. Descriptive analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics showed that those who begin ART treatment tended to be in their thirties residing in Tokyo or adjacent prefectures, with high education and full-time employment. Although Japan leads the world in the number of ART treatments performed per year, epidemiologic studies on the mental health and QOL of patients remain scarce. To our knowledge, this study presents one of the first opportunities to demonstrate the mental health status of Japanese women struggling with infertility and starting ART treatment to have a child. High prevalence of poor mental health at early stages of treatment is concerning because high stress has been associated with discontinuation of infertility treatment and may have profound influences on daily lives such as sexual functioning13,26.

Aligned with previous findings from Japan and other countries, women who go through ART treatments appeared to be highly stressed, indicated by depressive symptoms, high anxiety, and low QOL9. One study conducted in Japan showed that 32% of patients undergoing infertility treatment showed depressive symptoms, based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale27. In another Japanese study comprising 125 patients receiving ART or other infertility treatments, the average scores of STAI were 46.5 (SD 9.5) for trait and 48.6 (SD 8.6) for state28. Matsubayashi et al. showed that scores based on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Profile of Mood States were higher among infertility patients than pregnant women18. Our results were mostly consistent with these previous findings despite the differences in tools to assess mental health. A study by Ogawa et al., also showed elevated levels of anxiety and depression, but the prevalence appeared higher in older patients which was in contrast with our findings of higher prevalence among younger age groups20. To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined QOL among infertility treatment patients in Japan.

We showed in our study that women at early stages of the ART treatment were already showing signs of deteriorated mental health and QOL. Reasons for this tendency remain unknown and are to be examined, but one contributing factor may be the expectation of high treatment cost. The total treatment cost could easily reach up to a million Yen or more as they go through multiple cycles of treatment. Another factor may be related to time management needed to coordinate treatment and work issues. Because patients cannot know the schedule of treatment in advance, and frequent clinic visits are necessary, such time constraints could interfere with work. Japanese workers are known for their long work hours29, and the corporate culture may cause logistical difficulties for those working full-time. In our study, half of the women were working full-time.

Half of the participants noted that reasons for infertility were unknown. Thus, they do not know which treatment would be best for them to increase the chance of achieving pregnancy. This uncertainty regarding whether the selected treatment is the most effective for their condition may increase stress and anxiety levels. In Japan, the success rate of achieving pregnancy at each fertility clinic is often not available publicly to the patients, while in other countries such as the United States, government agencies publish summary reports30. This lack of information may add to the unforeseeable nature of ART treatment, which is likely to be one of the main sources of stress for patients.

Stratified by number of oocyte retrievals, number of children, and age, we observed certain patterns regarding depressive symptoms, anxiety, and QOL. For example, those with at least one child seemed to be better off mentally than those without. This observation may be influenced in part by the decision-making process of choosing to receive the treatment. Only those with suitable circumstances, such as financial capacity, may decide to receive infertility treatment to have another child. For others, the option may not even be available to them due to sub-optimal circumstances. In addition, for those who already have a child, treatment failures may not be as pressuring compared to those who desperately want a first child. High prevalence of depressive symptoms and low QOL among young participants may be explained by the general perception that age is a major contributing factor of infertility. The need for ART treatment may be perplexing and unpleasant to the young participants. Some may have serious health problems which could lead to infertility and also influence mental health negatively. In addition, because of the seniority system and employment structure in Japan, wages for young people tend to be low and may contribute to additional strain on mental health31,32.

Our results indicate the need for mental health care support for infertility treatment patients even at the early stages of the treatment. In other countries, intervention studies have been conducted to reduce distress among infertility treatment patients33. However, in Japan, such studies have been scarce despite the popularity of infertility treatment. In a study by Asazawa, it was reported that a partnership support program could reduce psychological distress among women34. The Japan Society for Reproductive Psychology has translated a publication by the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, “Routine psychological care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction—A guide for fertility staff” into Japanese, and this translated literature is made available on their website35.

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. Because we could not employ random sampling, our results may not accurately reflect the circumstance of the broad-level population receiving infertility treatment in Japan. There are no national data on socio-demographics of the women who go through ART treatments. We may be overestimating the prevalence of depressive symptoms, high anxiety, and low QOL because it is possible that those who wanted to address the difficulties of treatment may have had a higher likelihood of participation. However, the opposite is also conceivable in which those who were not doing well mentally might have had a tendency not to participate. Although we used validated scales such as QIDS, STAI, SF-12, they were not specifically designed to assess special populations such as those who go through ART treatment. In European countries, scales such as Copenhagen Multi-Centre Psychosocial Infertility Fertility Problem Stress Scales (COMPI-FPSS) and SCREENIVF have been developed and used with infertility treatment patients36,37, but these were not available in Japanese except for FertiQOL38,39. Scales designed for this special population may be necessary. Finally, it is important to note that this descriptive report is based on baseline data taken from a longitudinal survey; thus, it does not reflect the temporal sequence of events. For instance, we do not have access to the participants’ mental health information prior to their initiation of infertility treatment. However, epidemiologic studies on patients who undergo ART treatment are generally lacking in Japan. As such, we believe that descriptive data presented in the current report is important as basis to understanding the problem and informing the direction of future initiatives. Using data from the follow-up surveys, we plan to examine the trajectory of mental health and QOL and potential risk and protective factors that could influence the trajectory40.

Conclusion

Despite the high demand of ART treatments in Japan, studies examining potential negative effects of the infertility treatment on patients’ body and mind remain scarce. In addition to epidemiologic studies to confirm our findings, intervention studies to alleviate the stress of the ART treatment among patients may be needed.

Change history

17 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02389-7

References

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Summary of Vital Statistics in 2019 1–2 (Tokyo, 2019).

Ishihara, O. et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: A summary report for 2017 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod. Med. Biol. 19(1), 3–12 (2020).

Dyer, S. J., Vinoos, L. & Ataguba, J. E. Poor recovery of households from out-of-pocket payment for assisted reproductive technology. Hum. Reprod. 32(12), 2431–2436 (2017).

ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Economic aspects of infertility care: A challenge for researchers and clinicians. Hum. Reprod. 30(10), 2243–2248 (2015).

Fertility Information Network. Survey on economic burden of infertility treatment [in Japanese]. 2019. http://j-fine.jp/prs/prs/fineprs_Keizaiteki_anketo2018.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2020.

Domar, A. D. Creating a collaborative model of mental health counseling for the future. Fertil. Steril. 104(2), 277–280 (2015).

Huppelschoten, A. G. et al. Differences in quality of life and emotional status between infertile women and their partners. Hum. Reprod. 28(8), 2168–2176 (2013).

Schaller, M. A., Griesinger, G. & Banz-Jansen, C. Women show a higher level of anxiety during IVF treatment than men and hold different concerns: A cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 293(5), 1137–1145 (2016).

Chachamovich, J. R. et al. Investigating quality of life and health-related quality of life in infertility: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 31(2), 101–110 (2010).

Cousineau, T. M. & Domar, A. D. Psychological impact of infertility. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 21(2), 293–308 (2007).

Peterson, B. D. et al. Are severe depressive symptoms associated with infertility-related distress in individuals and their partners?. Hum. Reprod. 29(1), 76–82 (2014).

Crawford, N. M., Hoff, H. S. & Mersereau, J. E. Infertile women who screen positive for depression are less likely to initiate fertility treatments. Hum. Reprod. 32(3), 582–587 (2017).

Gameiro, S. et al. Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum. Reprod. Update 18(6), 652–669 (2012).

Pedro, J. et al. Couples’ discontinuation of fertility treatments: A longitudinal study on demographic, biomedical, and psychosocial risk factors. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 34(2), 217–224 (2017).

Boivin, J., Griffiths, E. & Venetis, C. A. Emotional distress in infertile women and failure of assisted reproductive technologies: Meta-analysis of prospective psychosocial studies. BMJ 342, d223 (2011).

Matthiesen, S. et al. Stress, distress and outcome of assisted reproductive technology (ART): A meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. 26(10), 2763–2776 (2011).

Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, J. et al. Just relax and you’ll get pregnant? Meta-analysis examining women’s emotional distress and the outcome of assisted reproductive technology. Soc. Sci. Med. 213, 54–62 (2018).

Matsubayashi, H. et al. Emotional distress of infertile women in Japan. Hum. Reprod. 16(5), 966–969 (2001).

Matsubayashi, H. et al. Increased depression and anxiety in infertile Japanese women resulting from lack of husband’s support and feelings of stress. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 26(5), 398–404 (2004).

Ogawa, M., Takamatsu, K. & Horiguchi, F. Evaluation of factors associated with the anxiety and depression of female infertility patients. BioPsychoSoc. Med. 5(1), 15 (2011).

Fujisawa, D. Assessment scales of conitive behavior therapy [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Clin. Psychiatry 39, 839–850 (2010).

Hidano, T. et al. STAI Manual (Jitsumukyouiku-shuppan, 2000).

Fukuhara, S. & Suzukamo, Y. Manual of SF-36v2 Japanese Version 7–10 (iHope International Inc., 2004).

Asazawa, K. Development and testing of a partnership scale for couples undergoing fertility treatment. J. Jpn. Acad. Nurs. Sci. 33(3), 3_14-3_22 (2013).

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Comprehensive survey of living condition. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/20-21.html. Accessed 6 May 2020.

Facchin, F. et al. Infertility-related distress and female sexual function during assisted reproduction. Hum. Reprod. 34(6), 1065–1073 (2019).

Akizuki, Y. Depression status of Japanese women who taking infertile treatment and associated factors [in Japanese]. J. Jpn. Soc. Obstet. Gynecol. 21(2), 178–185 (2016).

Igarashi, S. et al. Anxiety in women undergoing reproductive medical treatment [in Japanese]. Jpn. J. Maternal Health 49(1), 84–90 (2008).

Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training. Databook of International Labour Statistics 2018 (Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, 2018).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ART Success Rates. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/art/artdata/index.html. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Results of comprehensive survey of living conditions year 2017. 2018. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa17/dl/09.pdf. Accessed 12 May 2020.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Labor Survey summary. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/longtime/03roudou.html#hyo_9. Accessed 12 May 2020.

Frederiksen, Y. et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for psychological and pregnancy outcomes in infertile women and men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 5(1), e006592 (2015).

Asazawa, K. Effects of a partnership support program for couples undergoing fertility treatment. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 12(4), 354–366 (2015).

Gameiro, S. et al. ESHRE guideline: Routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction-a guide for fertility staff (Japan Society for Reproductive Psychology, Trans). Hum. Reprod. 30(11), 2476–2485 (2015).

Sobral, M. P. et al. COMPI Fertility Problem Stress Scales is a brief, valid and reliable tool for assessing stress in patients seeking treatment. Hum. Reprod. 32(2), 375–382 (2017).

Verhaak, C. M. et al. Who is at risk of emotional problems and how do you know? Screening of women going for IVF treatment. Hum. Reprod. 25(5), 1234–1240 (2010).

Asazawa, K. et al. Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) tool for couples undergoing fertility treatment. Open J. Nurs. 8(9), 616–628 (2018).

Kitchen, H. et al. A review of patient-reported outcome measures to assess female infertility-related quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 15(1), 86 (2017).

Rockliff, H. E. et al. A systematic review of psychosocial factors associated with emotional adjustment in in vitro fertilization patients. Hum. Reprod. Update 20(4), 594–613 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Kenichi Tatsumi, Dr. Toshihiro Kawamura, and Dr. Tomonori Ishikawa for their cooperation with the recruitment of participants. We also thank our public relations personnel (Mr. Koji Murakami and Ms. Rui Kondo) at the National Center for Child Health and Development, Ms. Riko Higashio, Mr. Yuji Yoshikawa, Dr. Daisuke Shigemi, and Mr. and Mrs. Kodama (@pocoloooog) for their support with the recruitment of participants. We also thank Ms. Masayo Watanabe, Dr. Kyoko Asazawa, Dr. Seung Chik Jwa, and Dr. Takakazu Saito for their valuable suggestions and Hiromi and Issei Nakano for administrative assistance.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Center for Child Health and Development internal grant, Pfizer Health Research Foundation, and Japan Center for Economic Research. The funders had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K., M.S., and K.S. have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. N.M. and K.U. have substantively revised the manuscript. All the authors have approved the submitted version and agreed both to be personally accountable for the author's own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in Affiliation 2, which was incorrectly given as ‘Department of Pediatrics, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, 1-5-45 Yushima, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-8519, Japan’. The correct affiliation is ‘Department of Pediatrics, Perinatal and Maternal Medicine (Ibaraki), Graduate School, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo 113-8519, Japan’.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kato, T., Sampei, M., Saito, K. et al. Depressive symptoms, anxiety, and quality of life of Japanese women at initiation of ART treatment. Sci Rep 11, 7538 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87057-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87057-6

This article is cited by

-

Effect of health education program on knowledge, stress, and satisfaction among infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization injection

Middle East Fertility Society Journal (2024)

-

Global prevalence of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety, stress, and depression among infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2024)

-

Effects of sex, age, choice of surgical orthodontic treatment, and skeletal pattern on the psychological assessments of orthodontic patients

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.