Abstract

While the association between assets and depression has been established, less is known about the link between financial strain and depression. Given rising financial strain and economic inequity due to the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding the role that financial strain plays in shaping population depression in the United States is particularly salient. We conducted a scoping review of the peer-reviewed literature on financial strain and depression published from inception through January 19, 2023, in Embase, Medline via PubMed, and PsycINFO, PsycArticles, SocINDEX, and EconLit via Ebsco. We searched, reviewed, and synthesized the literature on longitudinal studies on financial strain and depression conducted in the United States. Four thousand and four unique citations were screened for eligibility. Fifty-eight longitudinal, quantitative articles on adults in the United States were included in the review. Eighty-three percent of articles (n = 48) reported a significant, positive association between financial strain and depression. Eight articles reported mixed results, featuring non-significant associations for some sub-groups and significant associations for others, one article was unclear, and one article reported no significant association between financial strain and depression. Five articles featured interventions to reduce depressive symptoms. Effective interventions included coping mechanisms to improve one’s financial situation (e.g., mechanisms to assist in finding employment), to modify cognitive behavior (e.g., reframing mindset), and to engage support (e.g., engaging social and community support). Successful interventions were tailored to participants, were group-based (e.g., they included family members or other job seekers), and occurred over multiple sessions. While depression was defined consistently, financial strain was defined variably. Gaps in the literature included studies featuring Asian populations in the United States and interventions to reduce financial strain. There is a consistent, positive association between financial strain and depression in the United States. More research is needed to identify and test interventions that mitigate the ill effects of financial strain on population’s mental health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression is a common mood disorder, affecting millions of Americans and their families, employers, and communities. Almost one quarter of adults in the United States report symptoms consistent with depressive disorder at some point in their lives [1]. Depression is costly to individuals and communities [2] and is associated with a number of negative health indicators including substance misuse and early mortality [3]. Depression is also highly sensitive to social and economic conditions [4,5,6]. As such, changes in depression in response to economic conditions may present themselves much sooner than physical health indicators and may be an effective area for intervening to prevent worsening mental and physical illness.

Social and economic factors shape population’s mental health [7, 8]. Economic indicators such as having fewer assets are associated with depression [6, 9,10,11]. For example, having lower income [12], having less money in savings [9, 11], and not owning a home [11] are all objective economic assets that have been associated with higher prevalence of depression in US adults. Social assets such as educational attainment and marital status are also associated with depression, with greater education and being married, each associated with less depression [10]. Beyond objective assets, perceptions of limited assets—manifesting as financial strain—may additionally [13] and even more strongly predict depression than do objective economic indicators [14, 15].

Financial strain is a correlated, but separate, construct than objective financial assets. Financial strain broadly refers to the ability of people to cover their expenses with assets available, whether measured as the perception of strain or reactions to their inability to pay for needs. In this way, financial strain is a measure of the perception of assets. Financial strain may be a function of spending proportionate to resources available and perceptions of the ability to pay for needs; thus, financial strain may be relative, shaped by the perception of others’ prosperity. For example, in a study of older adults following the Great Recession from 2007–2009, overall financial strain and depression decreased between 2006 and 2010 despite people having objectively fewer assets than before the recession [15]; people may have perceived that others around them were worse off than they were, lessening the psychological blow of having lower home values, lower income, and lower savings [15]. Thus, it is possible that social comparison may influence perceptions of or reactions to needs and relative social standing [16]. Changes in the public dialog about the overall financial status of the population may also change people’s outlook on their own financial situations [17]. Psychological strain is itself associated with poor mental health [18]. Thus, it is possible that whether or not persons feel under financial strain may matter as much as, or more than, whether they do have adequate assets [15, 17]. While improving objective economic conditions may contribute to reductions in population depression, more information is needed about how financial strain specifically is independently associated with poor mental health and how to alleviate it.

Despite a growing awareness of how adverse life events may instigate poor mental health [19,20,21] and how a worse socioeconomic context influences the treatment of depression [22] (affecting the likelihood of recurrence [23, 24]), few reviews have assessed the relation between financial strain and depression. Given the complex relations between access to assets, perceptions of resources, and social comparison, documenting what we know about financial strain and depression may improve our understanding of the link between the two and point to potential interventions to reduce depression. Buckman et al. reviewed studies that assessed treatment prognosis among patients with depression across a range of socioeconomic indicators that include financial strain [25]. Guan et al. reviewed observational studies on financial strain and depression globally; their assessment included cross-sectional studies and concluded with a call for more research with longitudinal data [26]. This paper contributes to the literature by focusing on studies with longitudinally collected data that were conducted in the United States.

Understanding the relation between financial strain and depression is critical, particularly as the United States emerges from the COVID-19 economic recession that has disproportionately affected low-income populations. The COVID-19 pandemic has clearly increased economic inequities in the United States, with high-income earners emerging with more and low-income earners emerging with fewer assets than before the pandemic [27]. Financial strain also likely increased following the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among lower-income adults [28, 29]. While interventions to improve objective financial assets for people with fewer assets are critical, such efforts may be costly and politically fraught; interventions to address financial strain may be an additional lever in addressing and improving population mental health [17].

This paper aimed to scope the literature on financial strain and depression in the United States. Our research questions were: (1) What is the scope and nature of the peer-reviewed literature on financial strain and depression? (2) What is the relation between financial strain and depression? and (3) What interventions, if any, have been found to improve depression in the context of financial strain?

Methods

We conducted a scoping review in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines [30].

Search strategy

We searched Embase, Medline via PubMed, and PsycINFO, PsycArticles, SocINDEX, and EconLit via Ebsco from inception to January 19, 2023, using keywords and terms adapted to each database. A detailed search strategy can be found in Appendix A. Citations were deduplicated in EndNote. Abstracts were then loaded and screened for inclusion in Abstrackr software (http://abstrackr.cebm.brown.edu/). Abstrackr uses machine learning to predict the likelihood of relevance for each citation [31, 32]. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by the lead author (CE) and colleague (GR), and the Abstrackr software was used to prioritize relevant citations through the screening process. The full-text screening was carried out by the lead author (CE) and three additional readers (AF, AP, and GR). We also screened reference lists of related studies for relevant citations.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined in accordance with the guidance for systematic scoping reviews [33, 34].

Types of participants

We included studies featuring adults who were 18 years or older. We excluded studies about young adults that had aggregated samples with persons younger than 18 years of age.

Concept

We included longitudinal, quantitative articles that assessed the concept of depression and financial strain. Articles that assessed mental health broadly but did not disaggregate results by depression or psychological distress were not eligible for inclusion. Articles that did not measure subjective perceptions of financial strain (for example, articles that reported on objective measures of financial standing, such as wealth but did not have measures of financial strain) were excluded. We excluded studies that only controlled for financial strain as a covariable in their models and did not report on the relation between depression and financial strain. We also excluded articles that focused on postpartum depression, given the unique features of that important phenomenon [35]. We included related constructs such as economic stress, strain, or financial problems.

Context

We included studies conducted in the United States. The aim of the study was to understand the literature on financial strain and depression in the United States, given the varying nature of economic and financial strain across contexts; by limiting to the United States, we hoped to focus on literature within one country context to better understand the evolution of the understanding of these concepts in the United States over time.

Types of evidence sources

Articles published in the peer-reviewed literature were eligible for inclusion. Only articles published in the English language were included.

Data charting

We extracted the following information from eligible articles: year of publication, data source, sample size, sample description, sampling technique, study length, the definition of financial strain, number of items in the financial strain definition, number of times financial strain was measured, definition of depression, the relation between financial strain and depression, and a standardized summary. We calculated the percentage of articles by sampling technique, gender of populations studied, race/ethnicity of populations studied, number of items included in financial strain definition, number of times financial strain was measured, and assessment of depression used. We flagged studies that included and reported findings on depression-reduction interventions. We used a narrative synthesis to summarize the results.

Results

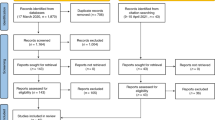

We screened 4004 unique citations for inclusion. Four hundred twenty-five abstracts were identified and reviewed in full text for eligibility; 367 full-text articles were excluded (n = 220 cross-sectional; n = 66 conducted in non-US countries; n = 42 duplicates; n = 1 could not retrieve full text; n = 1 review article; n = 29 did not assess relation between depression and financial strain; n = 3 non-adult populations; n = 1 postpartum depression; n = 4 US data aggregated with other countries). In total, 58 longitudinal, quantitative studies conducted in the United States were included in the review. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process. Appendix B shows the alphabetized citations of the 58 articles included in the review.

Article characteristics

Included articles were published between 1981 and 2022. Three studies were analyzed in multiple papers: the JOBS II study (n = 4), the Hispanic Established Population for Epidemiological Studies of the Elderly (n = 3), and the Iowa Youth and Family Project (n = 2). All other articles used a data source that only appeared once (n = 39) or was original to that study (n = 10). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the articles included in the review. Seventy-four percent of studies (n = 43) featured adults ages 18 years and older; 25.9% (n = 15) featured sample populations ages 50 years or older. Forty-seven percent of articles (n = 27) used a probability-based sampling design; 50% (n = 29) used a non-probability-based sampling design; 3.4% (n = 2) did not provide the sampling design. Seventy-two percent (n = 42) included male and female populations; 28% (n = 16) of articles featured only female populations; no articles featured only male populations. The majority of articles (74.1%, n = 43) featured populations identifying as White or Black (67.2%, n = 39). Forty-five percent of articles (n = 26) included “other” race/ethnicity groups, 32.8% (n = 19) explicitly stated that they included Hispanic persons, and 19% (n = 11) featured Asian persons.

Definitions of financial strain and depression

Financial strain was defined in a variety of ways. Almost three-quarters of the papers studied (74.1%; n = 43) used a measure for financial strain that included one, two, or three items. The earliest definition of financial strain that we included in the review was the 27-item Peri Life Events Scale by Dohrenwend et al. (1978), including the following indicators: “borrowed money to help pay bills,” “sold possessions or cashed in life insurance,” “changed food shopping or eating habits to save money,” and “sold the property to raise money” among others [36]. A more commonly used definition of financial strain emerged in 1981: a 9-item scale created by Pearlin et al. [37]. The scale included items ranging from the ability to pay for clothing, medical care, housing, food, leisure activities, transportation, and furniture; difficulty paying bills overall; and the ability to “make ends meet.” Later studies used different combinations of these nine items depending on the focus of their work. Six studies, published from 1987 through 2010, used some combination of the original Pearlin definition. Three studies used financial strain definitions derived from Conger et al. (1994), which assessed the ability of parents to make ends meet, to pay for what they needed “for a home, clothing, household items, a car, food, medical care, and recreational activities” and economic adjustments, or changes made in response to economic stress over the past year [38].

The remaining studies used a combination of de novo questions to define financial strain based on their specific research question. The modal number of times that financial strain was measured (as reported in the published articles) was two times (n = 21, 36.2%). Twenty-one percent of studies (n = 12) measured financial strain once and 17% (n = 10) of studies measured financial strain three times.

Depression was defined relatively consistently, using validated measures in most studies. The most used depression assessment was the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D), reported in 51.7% of articles (n = 30). The next most used depression assessments were the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (17.2%, n = 10) and the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview, PHQ-2, and PHQ-9 (each 3.4%, n = 2).

Association between financial strain and depression

A preponderance of articles (82.8%, n = 48) reported a significant positive association between financial strain and depression. Eight studies reported mixed findings, either showing significance for some groups but not others (such as in men but not women) or did not show a significant association in some groups (potentially due to sample size limitations). One study reported no association between financial strain or unemployment due to the COVID-19 pandemic and trajectories of depression over the COVID-19 pandemic for parents of children with chronic pain [39]. Hertz-Palmor et al. found that adults in the United States had an association between financial strain and depression at p = 0.07 [28]. McCormick et al. found that high but not moderate financial strain was significantly associated with depression [40]. Gutierrez et al. found that chronic financial strain was significantly associated with depression but not acute financial strain [41]. Yoshikawa et al. found that economic hardship was significantly associated with psychological distress at 14 months but not at 24 months of follow-up [42]. Mendes de Leon et al. found that financial strain was associated with future depression in men but not women [43]. Valentino et al. found that although low depression scores predicted lower levels of financial strain, higher depression scores did not predict the severity of financial strain [44]. One study, Robinson et al., showed inconsistent findings within the paper itself (with their table and figure showing conflicting numbers) [45]. There were no studies that showed a protective effect of financial strain on depression. It is possible that the direction of the relation between financial strain and depression goes both ways: Curran et al. found that financial strain at T1 did not predict depressive symptoms at T2 for either mothers or fathers, but depressive symptoms at T1 was associated with financial strain at T2, for mothers but not fathers [46]. However, Jones et al. found that depressive symptoms did not predict later financial strain among patients with cancer [47]. Table 2 shows the charted review, describing summary details of each included article.

Interventions

Five of the fifty-eight longitudinal articles featured depression reduction interventions. While the interventions did not relate directly to financial strain, some helped reduce financial strain indirectly, as detailed below. The five studies are detailed and described in chronological order.

JOBS II intervention for unemployed job seekers

Vinokur and Schul (1997) studied the JOBS II intervention for unemployed job seekers [48]. While three other articles used the JOBS II data, their study designs did not compare intervention arms to control groups (rather, they looked at specific arms or used study designs that did not incorporate intervention) [49,50,51]. The JOBS II intervention included five 4-hour sessions over 1 week for groups of 12 to 22 recently unemployed people looking for jobs. Two trainers (one man and one woman) led interactive workshops on enhancing job-search skills. The workshop taught job seekers to anticipate setbacks and overcome barriers, build self-esteem, improve job-search efficacy, and increase locus of control. The intervention was associated with re-employment, and a sense of mastery, both of which were associated with reductions in financial strain at 2- and 6-months post-intervention. Reduced financial strain was, in turn, associated with reduced depressive symptoms.

Fatherhood relationship and marriage education (FRAME) intervention for low-income families

Wadsworth et al. (2013) studied the Fatherhood Relationship And Marriage Education (FRAME) intervention in low-income families. FRAME was a “father-friendly, father-inclusive, family strengthening intervention” for couples [52] with three components: (1) education about strengthening marital relationships through positive communication skills, (2) stress and coping skills training, and (3) child-centered parent training. The stress and coping skill training focused on identifying life stressors such as financial strain and how to identify differences between circumstances and events that were readily solvable and those requiring different ways of coping. Couples were taught active problem-solving skills for problems with identifiable solutions (primary coping mechanisms). For stressors that could not be solved readily, couples were taught to use support, acceptance, and cognitive restructuring to cope (secondary coping mechanisms). The authors found that decreased financial strain predicted reductions in depressive symptoms for mothers and fathers. They also found that reductions in financial strain improved father-child relations.

Beat the blues (BTB) intervention for African American older adults

Szanton et al. (2014) studied the Beat the blues (BTB) intervention, conducted in participant homes by a licensed social worker that focused on education about depression, management of care, referral and linkage, stress reduction, and behavioral activation [53]. The population included African American adults ages 55 years or older with depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of 5 or greater). Participants were randomized into the BTB group (intervention group) or put on the waitlist (control group). The intervention included ten one-hour sessions weekly and then bi-weekly over a 4-month period. Components were tailored to participant care needs, preferred techniques for stress reduction, and personal activity goals. Financial strain and depression were measured at baseline and after the 4-month intervention. Participants in the BTB intervention reported lower depressive symptoms scores after the 4-month intervention relative to the control group. Participants who reported financial strain at the 4-month mark reported a 6.4-point reduction in the PHQ-9 score, while participants who reported no financial strain at the 4-month mark reported an 8.8-point reduction in the PHQ-9 score. There did not appear to be an interactive effect between financial strain, the intervention, and depressive symptoms. The BTB intervention did not appear to reduce the effects of financial strain on depression; the authors noted that the magnitude of the reduction in depressive symptoms was greater among persons with low financial strain and, therefore, that efforts to reduce financial strain could improve the effectiveness of depression interventions.

The progressively lowered stress threshold (PLST) model and family meeting strategy for unpaid caregivers of persons with dementia

Robinson et al. (2016) studied a two-part intervention on the mental health of unpaid family caregivers for persons with dementia (PWD) [45]. The two-part intervention included the Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model and a family meeting strategy based on Mittelman’s New York University intervention [54]. The PLST model was an in-home psychoeducational curriculum about behavior management for family caregivers. Individual plans were created in response to caregiver needs at baseline. The family meeting strategy included at least one three-to-four-hour family education session focused on the use of community resources and on managing upsetting behavioral symptoms. Researchers reported a decrease in depressive symptoms during the 6-month survey, which was maintained over time (thus, they found a decrease in depressive symptoms from baseline to 6 months and then a stable prevalence of depressive symptoms at 6-, 12-, and 18-months). Among caregivers reporting financial strain, there was a significant drop in depressive symptoms over time, whereas, among caregivers reporting no financial strain, the depressive symptoms remained constant. The authors concluded that caregivers experiencing financial strain may benefit most from the intervention.

The protecting strong African American families (ProSAAF) for African American couples with children

Barton et al. (2018) studied the Protecting Strong African American Families (ProSAAF) intervention, which included six 2-hour sessions at participants’ homes in small towns and communities in Georgia. Sessions were led by trained facilitators from the region. Sessions focused on stressors such as racial discrimination and financial strain and provided African American couples with behavioral and cognitive techniques for handling stressors, including communication strategies between the couples. Children were invited to join the final 30 minutes of each session. Participants were surveyed at baseline, 9-month follow-up, and 17-month follow-up. Financial hardship was associated with reductions in relationship satisfaction, communication, confidence, and with increases in depressive symptoms (β = 0.82 [0.18], p < 0.07). There was an interactive effect of financial hardship with the intervention on relationship confidence but not depression. Thus, the authors found that the intervention modified the effect of financial strain on relationship confidence, but the intervention did not modify the effect of financial strain on depression.

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the interventions. While four of five interventions reduced depression, only two interventions (JOBS II and FRAME) appeared to reduce financial strain directly or indirectly and, in turn, reduce depression. Successful interventions had several characteristics in common: they were hosted over multiple sessions (rather than at one time), were led by trained facilitators, and were tailored to individual participants. All interventions highlighted in some ways the importance of social dynamics and contexts shaping health outcomes; for example, two studies included dyads and a third included a family session as part of the intervention. Effective interventions included coping mechanisms to improve one’s financial situation (i.e., finding employment), to modify cognitive behavior (i.e., reframing mindset), and to engage support (i.e., engaging social and community support). These findings highlight the importance of social networks and social support in shaping depression and its relation to stressors such as financial strain. Interventions were geared more toward reducing depression than addressing financial strain, pointing to a gap in the literature.

Discussion

We aimed to scope the literature, to understand the relation between financial strain and depression, and to identify interventions to reduce depression. We found, first, a robust literature on financial strain and depression; while depression was consistently defined throughout the literature, financial strain was not. There were a substantial number of studies with female-only samples and none with male-only samples; multi-gender studies allow for comparison across genders, which can lead to a better understanding of the impact of financial strain on mental health across genders. Second, we found that financial strain was associated with depression across the literature. Eighty-eight percent of studies included found a significant, positive association between financial strain and depression. Thus, despite differences in the definition of financial strain, it was consistently positively associated with depression. Third, we identified five longitudinal articles that featured interventions to reduce depressive symptoms and included financial strain in their analyses. In four of the five studies, the intervention reduced depressive symptoms over time. It should be noted that these studies did not explicitly aim to reduce financial strain.

This article is consistent with the several articles that have reviewed constructs of financial strain and depression and contribute to a new synthesis of studies conducted within the United States. In their review of 40 global, observational studies quantifying the relation between financial strain and depression, Guan et al. found a positive association between measures of financial stress and depression in most studies, with stronger associations for populations with low income or low wealth [26]. Additionally, they found stronger associations between relative assets than absolute assets. Our study differs from Guan et al.’s in multiple ways; centrally, we included only longitudinal studies, and we focused on studies conducted in the United States, allowing for a more detailed synthesis of intervention designs. In a systematic review of different socioeconomic indicators, including financial strain and depression prognosis in randomized control trials, Buckman et al. found that struggling financially was related to worse depression prognosis; however, they found that controlling for employment attenuated the relationship and that there was no evidence of a significant association between financial strain and depression prognosis at 9–12 months [25]. Articles included in the review by Buckman et al. were all based in the United Kingdom, which has universal health coverage. Thus, the findings from these studies may not be directly relevant to the United States, where financial strain may have a stronger association with depression, given less generous social policies. In a study of the role of wealth and income in shaping depression in older adults across 16 European countries, Kourouklis et al. found that the relation between economic conditions and depression varied across regions and that neither wealth nor income was significantly associated with depression in Nordic countries, which have more generous social policies [55]. In this way, individual wealth and income may have had less of an effect on mental health because economic conditions—and financial needs that could result in financial strain if unmet—were being met through government or other societal structures. Thus, they concluded that the relation between economic precarity and depression may be stronger in countries that have less generous social policy.

This review is also consistent with previous reviews that have assessed the social and economic factors that shape mental health. As early as 1980, Dooley and Catalano documented the literature showing that negative economic change was associated with subsequent increases in behavioral disorders [56]. Muntaner et al. reviewed studies between 1999 and 2003 that used language around “social class” or “socioeconomic status” and major psychiatric disorders; they found that reduced socioeconomic position was associated with major mental disorders [4]. Pollack et al. reviewed studies from 1990 to 2006 assessing the relation between wealth and health outcomes more broadly. They identified six studies at the time that examined the relation between mental health and wealth, finding that five of the six studies identified a significant relation between low wealth and mental health in subsamples or the entire samples studied [6]. Osypuk et al. conducted a review of social and economic policies and their effect on health. They focused on four policy domains—housing, employment, marriage/family strengthening, and income support—across several health factors, including mental health. They identified 15 studies that measured mental health indicators following policy implementation and reported that 8 of these studies documented a health benefit of the policy [5]. Mair et al. reviewed the literature on neighborhood factors and mental health, identifying 45 articles published from 1990 to 2007. They found that more articles featured the association between depression and social processes (such as social interactions, violence, and disorder) than structural features (such as built environment and socioeconomic and racial composition of neighborhoods) and called for more literature to assess the causal effects of area characteristics on depression [57]. Wetherall et al. reviewed studies from inception to 2017 on social rank and depression; they synthesized 70 articles by the following measurements: social comparison scale (n = 32), subjective social status (n = 32), and other indicators of social rank (n = 6). They concluded that the majority of studies found that lower social rank was associated with more depressive symptoms [58]. They called for more research to better understand how one’s perception of social position compared to others relates to depression. Thus, the current review is consistent with other reviews on social and economic factors in shaping mental health but adds clarity to the literature on the perception of financial standing—i.e., financial strain—and depression in particular.

We identified a gap in the literature on the relation between financial strain and depression among racial and ethnic minoritized populations and migrant and refugee populations in particular, which have recently been highlighted by international bodies as an important population to consider [59, 60]. We found that Asian populations were the least represented racial group in this review. In the United States, the relation between assets and depression among racial and ethnic minoritized populations is complex [61], with non-US-born persons reporting better mental health than US-born counterparts and with paradoxical findings on depression emerging that may be in part explained by unequal access to assets [10]. Additionally, work outside of the United States has shown the associations between economic stressors and mental health among minoritized populations [62] through differential access to healthcare and employment opportunities, despite interventions to support the mental health of minoritized groups [63, 64]. Populations who migrate are a diverse group [60] with different financial situations; expanding research on this group could help illuminate the different experiences that this group has and how they may shape mental health more broadly. Given heightened exposure to stressors such as financial strain in racial and ethnic minoritized populations and among many populations who migrate, future work focusing on interventions to reduce economic inequities and improve depression among these populations could potentially improve mental health in these groups.

Of the fifty-eight longitudinal studies identified, only five featured interventions to reduce depression, and only two aimed to measure a reduction in financial strain from the intervention (as opposed to measuring differences in the efficacy of interventions on reducing depression by financial strain status). One of these two studies implemented an intervention to help recently unemployed job seekers gain re-employment [48], while the other study implemented an intervention to help parents cope with stressors such as financial strain, including primary coping (i.e., problem-solving to regain employment) and secondary coping (i.e., cognitive restructuring and engaging social support) [52]. The intervention studies highlighted several features of the relation between financial strain and depression. For example, they drew attention to the importance of social support, which moderated the relation between financial strain and depression in many of the non-intervention studies. Interventions were tailored to individuals, and families were included, recognizing the role of context in shaping depression. Given the limited literature on men in particular, the FRAME intervention provides an important focus on the relation among financial strain, depression, and broader family context among men and the potential benefits of coping interventions [52]. However, the overall limited number of interventions focused on reducing financial strain, which is clearly associated with depression, speaks to a larger gap in the literature and calls for research in the future that includes interventions to address and reduce financial strain. In a review specifically conducted on reducing the impact of financial hardship on depression, Moore et al. find that ‘job club’ programs targeted at unemployed persons may be effective, although more current and varied data are needed [65].

This review should be considered in light of two limitations. Because we selected articles that reported the relation between depression and financial strain, it is possible that the articles selected may embed publication bias. That is, studies that controlled for financial strain and did not find a significant relation between depression and financial strain may have been less likely to be in the published literature and, therefore, may be excluded from our analyses. Therefore, the studies represented in this review may reflect a stronger relation between financial strain and depression; however, no literature to date has shown that financial strain is associated with less depression, suggesting that the association remains an important factor in the context that shapes health outcomes. Second, it is possible that there is work on related and contributory constructs that do not use the terms captured in our search strategy and were not included in our review. We aimed to do a comprehensive search of the literature across disciplines, but it is possible that there are other works that assess the role of subjective relations to money and related concepts that were not captured in this review.

Notwithstanding these limitations, these findings suggest that the association between financial strain and depression over time has been well established. While the definition of financial strain varies, the patterns that have emerged are clear: having more financial strain is associated with poor mental health. The literature has gaps that should be addressed, such as an under-representation of Asian populations in studies conducted in the United States and of other minoritized ethnic groups in many studies worldwide. The literature also lacks standard definitions and measurement approaches to financial strain, making it challenging to compare findings across studies, that merit further attention. Additionally, there is a paucity of studies on interventions in the United States that may reduce the ill effects of financial strain on depression, and much work can be done to identify ways to reduce financial strain (and prevent depression) and to mitigate its consequences. While addressing the root causes of financial strain are costly, the costs of not addressing depression continue to rise. It is costly not to invest in the prevention of mental illness [66]. Estimates suggest that depression cost the US $326 billion in 2018, with a rising share being shouldered by workplaces [67]. With elevated levels of depression reported during the COVID-19 pandemic [68] and adolescents aging into adulthood, the burden of poor mental health is likely to rise, along with costs to individuals, employers, and families. Addressing financial strain, particularly as economies grapple with inflation and adjust to a post-COVID-19 world, may help to reduce the burden of depression. Additionally, coping mechanisms suggested in the interventions may provide benefits for a host of life stressors beyond financial strain. Interventions to improve financial strain and depression could be valuable in multiple ways, given the potential multidirectional relations between financial strain and recurrent depression—and recurrent depression on financial standing. Therefore, intervening at different levels may be a cost-effective, politically appealing solution and may lead to improved mental health in the face of multiple stressors [53].

Conclusion

Financial strain is a formidable factor associated with depression in populations. The association between financial strain and depression is consistent, positive, and significant in the United States. The divergent economic outcomes following the COVID-19 pandemic [27] may contribute to greater financial strain and divergent mental health outcomes across populations [69]. As the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are felt, attention should be paid to financial strain and its attendant consequences on population’s mental health, with possibilities of increased mental health burden in the months and years to come.

References

Vahratian A (2021) Symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder and use of mental health care among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, August 2020–February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:490–94.

Kessler RC. The costs of depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:1–14.

Galea S, Ettman CK. Mental health and mortality in a time of COVID-19. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:S73–4.

Muntaner C. Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:53–62.

Osypuk TL, Joshi P, Geronimo K, Acevedo-Garcia D. Do social and economic policies influence health? A review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2014;1:149–64.

Pollack CE, Chideya S, Cubbin C, Williams B, Dekker M, Braveman P. Should health studies measure wealth?: a systematic review. Am J Preventive Med. 2007;33:250–64.

Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26:392–407.

Allen J, Marmot M, World Health Organization, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (2014) Social determinants of mental health.

Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Galea S. Is wealth associated with depressive symptoms in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;43:25–31.e1.

Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Abdalla SM, Galea S. Do assets explain the relation between race/ethnicity and probable depression in U.S. adults? PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0239618.

Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Vivier PM, Galea S. Savings, home ownership, and depression in low-income US adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;56:1211–9.

Patel V, Burns JK, Dhingra M, Tarver L, Kohrt BA, Lund C. Income inequality and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. World Psychiatry. 2018;17:76–89.

Dijkstra-Kersten SMA, Biesheuvel-Leliefeld KEM, van der Wouden JC, Penninx BWJH, van Marwik HWJ. Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:660–5.

McGovern P, Nazroo JY. Patterns and causes of health inequalities in later life: a Bourdieusian approach. Sociol Health Illn. 2015;37:143–60.

Wilkinson LR. Financial strain and mental health among older adults during the Great Recession. GERONB. 2016;71:745–54.

Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7:117–40.

Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Economic hardship across the life course. Am Sociol Rev. 1999;64:548.

Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health—a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:443–62.

Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the “Kindling” Hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychol Rev. 2005;112:417–45.

Monroe SM, Anderson SF, Harkness KL. Life stress and major depression: the mysteries of recurrences. Psychol Rev. 2019;126:791–816.

Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. AJP. 1999;156:837–41.

Brown GW, Harris TO, Kendrick T, Chatwin J, Craig TKJ, Kelly V, et al. Antidepressants, social adversity and outcome of depression in general practice. J Affect Disord. 2010;121:239–46.

Monroe SM, Torres LD, Guillaumot J, Harkness KL, Roberts JE, Frank E, et al. Life stress and the long-term treatment course of recurrent depression: III. Nonsevere life events predict recurrence for medicated patients over 3 years. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:112–20.

Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229–33.

Buckman JEJ, Saunders R, Stott J, Cohen ZD, Arundell L-L, Eley TC, et al. Socioeconomic indicators of treatment prognosis for adults with depression: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:406.

Guan N, Guariglia A, Moore P, Xu F, Al-Janabi H. Financial stress and depression in adults: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0264041.

Long H, van Dam A, Fowers A, Shapiro L (2020) The covid-19 recession is the most unequal in modern U.S. history. The Washington Post.

Hertz-Palmor N, Moore TM, Gothelf D, DiDomenico GE, Dekel I, Greenberg DM, et al. Association among income loss, financial strain and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: evidence from two longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2021;291:1–8.

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S, et al. Low assets and financial stressors associated with higher depression during COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:501–8.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Rathbone J, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P. Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Syst Rev. 2015;4:80.

Trikalinos T, Wallace B, Jap J, Senturk B, Adam G, Smith B, et al. 41st annual meeting of the society for medical decision making, Portland, Oregon, October 20–23, 2019. Med Decis Mak. 2020;40:E1–E379.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid-Based Healthc. 2015;13:141–6.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, Editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12..

Wang D, Li Y-L, Qiu D, Xiao S-Y. Factors influencing paternal postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:51–63.

Dohrenwend BS, Askenasy AR, Krasnoff L, Dohrenwend BP. Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: the PERI life events scale. J Health Soc Behav. 1978;19:205.

Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22:337.

Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev. 1994;65:541.

Law EF, Zhou C, Seung F, Perry F, Palermo TM. Longitudinal study of early adaptation to the coronavirus disease pandemic among youth with chronic pain and their parents: effects of direct exposures and economic stress. Pain. 2021;162:2132–44.

Mccormick N, Trupin L, Yelin EH, Katz PP. Socioeconomic predictors of incident depression in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:104–13.

Gutierrez IA, Park CL, Wright BRE. When the divine defaults: religious struggle mediates the impact of financial stressors on psychological distress. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2017;9:387–98.

Yoshikawa H, Godfrey EB, Rivera AC. Access to institutional resources as a measure of social exclusion: Relations with family process and cognitive development in the context of immigration. N. Directions Child Adolesc Dev. 2008;2008:63–86.

Mendes De Leon CF, Rapp SS, Kasl SV. Financial strain and symptoms of depression in a community sample of elderly men and wWomen: a longitudinal study. J Aging Health. 1994;6:448–68.

Valentino SW, Moore JE, Cleveland MJ, Greenberg MT, Tan X. Profiles of financial stress over time using subgroup analysis. J Fam Econ Iss. 2014;35:51–64.

Robinson KM, Crawford TN, Buckwalter K. Outcomes of a two-component, evidence- based intervention on depression in dementia caregivers. Best Pract Ment Health. 2016;12:25–42.

Curran MA, Li X, Barnett M, Kopystynska O, Chandler AB, LeBaron AB. Finances, depressive symptoms, destructive conflict, and coparenting among lower-income, unmarried couples: a two-wave, cross-lagged analysis. J Fam Psychol. 2021;35:489–99.

Jones SMW, Nguyen T, Chennupati S. Association of financial burden with self-rated and mental health in older adults with cancer. J Aging Health. 2020;32:394–400.

Vinokur AD, Schul Y. Mastery and inoculation against setbacks as active ingredients in the JOBS intervention for the unemployed. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:867–77.

Vinokur AD, Price RH, Caplan RD. Hard times and hurtful partners: how financial strain affects depression and relationship satisfaction of unemployed persons and their spouses. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1996;71:166–79.

Vinokur AD, Schul Y. The web of coping resources and pathways to reemployment following a job loss. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7:68–83.

Price RH, Choi JN, Vinokur AD. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: how financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7:302–12.

Wadsworth Martha E, Rindlaub L, Hurwich-Reiss E, Rienks S, Bianco H, Markman HJ. A longitudinal examination of the adaptation to poverty-related stress model: predicting child and adolescent adjustment over time. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42:713–25.

Szanton SL, Thorpe RJ, Gitlin LN. Beat the blues decreases depression in financially strained older African-American adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:692–7.

Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Ambinder A, Mackell JA, et al. A comprehensive sSupport program: effect on depression in spouse-caregivers of AD patients1. Gerontologist. 1995;35:792–802.

Kourouklis D, Verropoulou G, Tsimbos C (2019) The impact of wealth and income on the depression of older adults across European welfare regimes. Ageing Soc. 2019;40:2448–79.

Dooley D, Catalano R. Economic change as a cause of behavioral disorder. Psychol Bull. 1980;87:450–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.87.3.450

Mair C, Diez Roux AV, Galea S. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:940–6.

Wetherall K, Robb KA, O’Connor RC. Social rank theory of depression: a systematic review of self-perceptions of social rank and their relationship with depressive symptoms and suicide risk. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:300–19.

World Health Organization. World report on the health of refugees and migrant. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

Galea S, Ettman CK, Zaman M. Migration and health. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2022.

Ettman CK, Koya SF, Fan A, Robbins G, Shain J, Cozier Y, et al. More, less, or the same: a scoping review of studies that compare depression between Black and White U.S. adult populations. SSM - Mental Health. 2022;2:100161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2022.100161.

Barnett P, Mackay E, Matthews H, Gate R, Greenwood H, Ariyo K, et al. Ethnic variations in compulsory detention under the Mental Health Act: a systematic review and meta-analysis of international data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:305–17.

Memon A, Taylor K, Mohebati LM, Sundin J, Cooper M, Scanlon T, et al. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012337.

Arundell L-L, Barnett P, Buckman JEJ, Saunders R, Pilling S, et al. The effectiveness of adapted psychological interventions for people from ethnic minority groups: a systematic review and conceptual typology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;88:102063.

Moore THM, Kapur N, Hawton K, Richards A, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D. Interventions to reduce the impact of unemployment and economic hardship on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2017;47:1062–84.

McDaid D, Park A-L, Wahlbeck K. The economic case for the prevention of mental illness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:373–89.

Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, Simes M, Berman R, Koenigsberg SH, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). PharmacoEconomics. 2021;39:653–65.

Ettman CK, Fan AY, Subramanian M, Adam GP, Badillo Goicoechea E, Abdalla SM, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. SSM - Popul Health. 2023;21:101348.

Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Abdalla SM, Sampson L, Trinquart L, Castrucci BC, et al. Persistent depressive symptoms during COVID-19: a national, population-representative, longitudinal study of U.S. adults. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;5:100091.

Barton AW, Beach SRH, Bryant CM, Lavner JA, Brody GH. Stress spillover, African Americans’ couple and health outcomes, and the stress-buffering effect of family-centered prevention. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32:186–96.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CKE: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft; AYF, APP, and GR: Formal analysis, investigation, and writing—review and editing; GPA: Methodology, software, and writing—review and editing; MAC, IBW, and PMV: Conceptualization, methodology, and writing—review and editing; SG: Supervision, conceptualization, methodology, and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ettman, C.K., Fan, A.Y., Philips, A.P. et al. Financial strain and depression in the U.S.: a scoping review. Transl Psychiatry 13, 168 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02460-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02460-z

This article is cited by

-

Assets and depression in U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review

Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (2024)