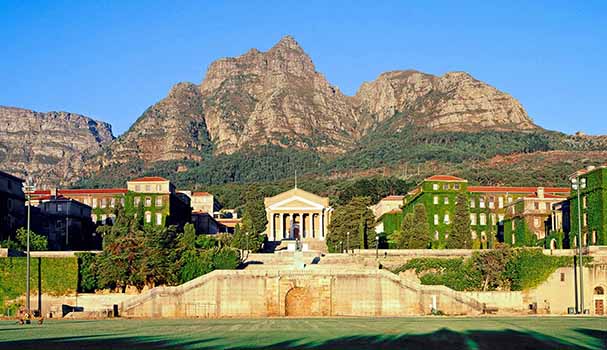

The University of Cape Town (above) is the Max Planck Society's top academic collaborator in Africa.

Credit: Eric Nathan / Alamy Stock Photo

The perils of perpetuating postcolonial biases in research

A proliferation of partnerships between academics and development practitioners pose ethical and practical concerns.

5 February 2018

Eric Nathan / Alamy Stock Photo

The University of Cape Town (above) is the Max Planck Society's top academic collaborator in Africa.

Joint research between academics and development organisations is increasing, but iniquitous practices risk prolonging the power imbalances characteristic of colonialism, researchers say.

In the Nature Index, partnerships between academics and non-profits in the production of high-quality papers have increased from 28,351 in 2012 to 48,899 in 2016. The majority of inter-region partnerships are between academic and non-profit institutions in Europe and North America, numbering almost 12,000 links.

The collaborations are driven by mutual need. Universities need to show funders the impact of their work, and development organisations need to deliver projects based on evidence.

Hover your mouse over a region on either axis to see how many partnerships institutions in one region have formed with institutions in another region.Nic Cheeseman and Susan Dodsworth, both democracy researchers at the University of Birmingham, have published a research note in African Affairs discussing the potential and pitfalls of these maturing relationships in the African context, though their advice is also relevant more broadly.

1. Shed colonialist biases

Research collaborations between academics and development organisations could fuel concerns “that Western scholars have reduced Africa to a ‘testing ground’ for their theories,” notes the analysis. “If collaborations are to avoid perpetuating power imbalances entrenched by colonialism, this needs to change,” says Cheeseman.

Including African researchers in the design and conduct of research, rather than simply bringing them in at a later stage when key decisions have been made is a good starting point, he adds.

In the Nature Index, institutions in Africa primarily partnered with those in Europe, followed by North America. The Max Planck Society in Germany has engaged in the most productive partnerships with African universities over the past five years, contributing to high-quality research papers with the University of Cape Town, the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and the University of Johannesburg, among others.

Jamie Monson, Africa historian at Michigan State University, is co-director of the Alliance for African Partnerships (AAP), which seeks to correct the view of Africa as merely a site for data collection. In 2016, the AAP led a three-day workshop with 14 representatives from African research institutions to help shape the alliance’s activities.

The process of working through equitable partnership can be time-consuming, yet the benefits make this extra commitment worthwhile, she says. “This model will lead to enhanced capacity for all of our scholars and institutions, and to better research practices and outcomes that will bring positive transformation for Africa.” The top African institution in the Nature Index, the University of Cape Town, had a weighted fractional count (WFC) of 13 in 2016, compared to the top institution in North America, Harvard University, which had a WFC of 750.

2. Protect the quality of consent

Ethical research is based on consent, whereby participants agree to taking part in the study. The involvement of development organisations could corrupt the quality of this consent, as research subjects might feel coerced into cooperating, to avoid losing access to the resources and opportunities they provide.

Academics need to assure potential research participants that a refusal to participate won’t exclude them from the benefits of development programmes, says Cheeseman. Designing fieldwork carefully, he adds, can ensure that these assurances are credible.

3. Be critical friends, not cheerleaders

It’s easy to fall into the trap of assuming that practitioners won’t want to hear criticism, but our experience shows that this is often not the case, says Cheeseman.

Like most people, many practitioners are willing to listen to criticism, as long as it’s constructive, he says. Sometimes practitioners want academics to offer the criticisms that they as insiders find difficult to voice.

Maintaining financial and geographical separation can also help to establish the distance needed to evaluate projects more objectively.

In 2017 Jude Fransman, a sociologist at Open University, published a guide for engagements between higher-education institutions and international non-governmental organisations. Global case studies revealed the importance of rethinking partnerships as long-term relations, built on trust.

4. Give researchers freedom

Academics need to be prudent when engaging in collaborations with development organizations, and not agree to contracts that limit their intellectual property rights over the research.

Partners might, for example, require researchers to sign non-disclosure agreements or to submit manuscripts for review by internal partners prior to publication. “Contracts that give development organizations a veto over what can be published should be avoided,” advise Cheeseman and Dodsworth in their paper.

Data analysis by Bo Wu.