Abstract

The paper investigates the possible mechanism behind the link between monetary policy and bank lending/risk-taking behaviors. Using a sample of Vietnamese commercial banks during 2007–2019, we find that the impact on bank output associated with monetary policy shocks is attributable to banks’ incentives to search for yield. Concretely, if interest rates remain lower amid monetary expansions, banks are likely to expand their lending activities more aggressively and take more risks to offset their reduced revenues. Moreover, this crucial supply-side effect is also at work for the bank liquidity creation channel of monetary policy transmission. Accordingly, we document that demotivated banks appear to undermine the impact of monetary policy on the core function of banks in creating liquidity to the real economy. Our finding is robust against a series of alternative monetary policy indicators, different bank output measures, multiple search-for-yield proxies, and substitute econometric methodologies. In sum, as the monetary policy pass-through transmission through the key banking channels is found due to banks’ own decisions, monetary authorities need to take this underlying mechanism into account when setting their monetary policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The responses of banks are crucial to understanding how monetary policy induces an impact on the real economy. Since the global crisis of 2008, one has seen a renewed interest in analyzing the importance of banks in monetary policy pass-through. This is described under the bank lending channel as first suggested by Bernanke and Blinder (1988), which implies that monetary policy shocks, both contractionary and expansionary, modify banks’ loan supply. Also, while the causes of the crisis were multifaceted, one has often attributed monetary policy as the essential factor leading to excessive risk-taking behavior of banks (Altunbas et al., 2012). In this vein, scholars have referred to the transmission of monetary policy via the bank risk-taking channel, which expresses that a low-interest-rate environment could increase banks’ risk tolerance (Borio and Zhu, 2012). Since banks constitute a dominant part of the financial system and offer a major funding source to fuel the economy, the monetary policy-bank output nexus has critical implications for policy designs, financial stability, and economic extension in many countries.

The potential influences of monetary policy could be detected via various mechanisms that identify shifts in the supply and demand for banks’ investments. One of the most effective mechanisms is through banks’ incentives to search for yield. Theoretically, monetary policy changes in the form of lower interest rates could leave many banks with eroded profitability searching for yield and hence risk, and they are also willing to expand lending aggressively (Rajan, 2006). The incentive of “search for yield” is explicitly conspicuous if return targets of banks are rigid and thus prompt their activities to “more pain, more gain” projects. Our aim in this study is to analyze the interesting topic of the bank lending/bank risk-taking channels of monetary policy, investigating the mechanism behind the pass-through. In particular, we perform a series of empirical tests to clarify whether the incentive to “search for yield” works in the monetary policy transmission. The key concept here is if bank incentives are at the heart of the functioning of the banking channels and certain banks are thought to be more driven by monetary policy than other counterparts, their different shifts in reaction to monetary policy changes can shed light on causal effects of the pass-through.

Our paper differs from earlier works in several dimensions. First, while most of the existing research observes how banks’ reaction to monetary policy shocks varies based on their bank-specific characteristics (e.g., bank size, liquidity, capitalization, ownership structure, and bank riskiness) or distinct aspects of the economy (e.g., financial deregulation, market competition, and financial integration) (see section 2 for a careful review), we in particular ask whether the search-for-yield incentives work in the supply side as an underlying mechanism behind the pass-through. In a nutshell, previous literature has not paid precise attention to the underlying mechanism based on the bank incentive of “search for yield” behind the link between monetary policy and bank output. Second, beyond examining whether the “search-for-yield” mechanism exists behind the pass-through via the bank lending channel, we also explore the causal workings of the bank risk-taking channel simultaneously. Significantly, we extend our investigation to answer whether there is a significant relationship between monetary policy and bank liquidity creation, which constitutes the novel bank liquidity creation channel of monetary policy. The findings from all these three essential banking channels might together reveal exactly the mechanisms through which monetary policy shocks are translated into bank behaviors.

To conduct empirical analysis, we employ data from the Vietnamese banking sector for the period 2007–2019. We focus on the loan growth rate for the bank lending channel, the Z-score index for the bank risk-taking channel, and comprehensive liquidity creation measures as invented by Berger and Bouwman (2009) for the bank liquidity creation channel. Instead of exploiting one single monetary policy indicator, we explore three different types of interest rates, including refinancing rates, rediscounting rates, and lending rates, to provide a broader overview of the research topic. Moreover, it is acknowledged that the multiple interest-rate-policy setting is necessary because different interest rates affect economic variables differently and to different degrees (Varlik and Berument, 2017). For the regression estimates, we apply the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator in the main result subsections, and then we check our obtained patterns using the static model with fixed effects and corrected Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. Consistency from these different econometric methodologies is ideal to ensure the robustness of our results and the reliability of our findings.

Vietnam provides a productive laboratory to investigate the research issue. Accordingly, the capital market in Vietnam is relatively underdeveloped, and most economic growth motivation is massively reliant on banks. This context potentially suggests a more pronounced existence and more practical importance of the monetary policy pass-through in the banking channels (Dang and Huynh, 2022a). Regarding monetary policy implementation, the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) simultaneously employs various tools to pursue its multiple targets. Regardless of the significant adjustments in magnitude and frequency, the interest-rate framework has never been close to the zero bound, which is expected to produce unbiased/consistent estimates from asymmetric policy indicators. Besides, after joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007, the Vietnamese banking sector has been subject to various reforms, especially the market opening to foreign participants and enhancing competitive forces (Nguyen et al. 2018). With a modified market structure, banks are asked to put much more effort into business strategies to earn desired profits. Hence, the search-for-yield incentives of banks are expected to experience multiple transformations over the past decade.

We contribute to the literature in three main ways. First, we analyze the link between monetary policy and bank output in a much more comprehensive manner compared to prior works by looking at all three key channels of bank lending, bank risk-taking, and bank liquidity creation. Our combination in this paper on the link between monetary policy and various bank output measures is entirely novel. Hence, it provides a better and more precise understanding of how monetary policy pass-through works for monetary authorities and banking regulators. Interestingly, in this vein, we fill the gap in the monetary policy literature by addressing how monetary policy hits bank liquidity creation, which covers both on- and off-balance sheet components. Accordingly, we extend the bank lending channel literature by widening the focus to bank liquidity creation — which includes much more than lending — especially in the context that research on the bank liquidity creation channel of monetary policy is still very limited. Second, we allow for the “search-for-yield” incentive of banks in the relationship between monetary policy and bank output — a research issue that has been ignored in the empirical works thus far despite its intuitive appeal. To our knowledge, our paper is the first to directly explore the presence of this bank incentive on the supply side. Hence, clarifying moderating conditions for the nexus between monetary policy and bank output could be helpful to derive policy implications for monetary authorities (i.e., in the route of whether the demand-side or supply-side effects are at work). Third, we perform our empirical analysis while accounting for multiple monetary interest rates that the central bank utilizes for setting its monetary policy. In this regard, a multiple-tool regime may deliver a more comprehensive understanding than a single-tool setup.

Research context

The Vietnamese economy

Vietnam, an emerging economy, has undergone consistent economic reform since the mid-1980s, transitioning from a centrally planned system to a market-oriented one. This shift has garnered praise from various stakeholders, resulting in impressive economic growth (Su et al., 2020).

A primary catalyst behind the economic prosperity in Vietnam resides in the persistent growth of its financial markets and the evolution of its banking system (Dang and Huynh, 2023). Nevertheless, Vietnam shares typical attributes with emerging markets, which frequently exhibit underdeveloped capital markets and regulatory frameworks, coupled with rapid and tumultuous transformations. In addition, it is imperative to underscore that government policies play a pivotal role in upholding the integrity and stability of the financial landscape, a fundamental prerequisite for sustained long-term economic advancement (Vo, 2016).

The Vietnamese banking sector

Since the late 1980s, Vietnam’s banking sector has expanded significantly, transitioning from a single bank system to a diverse network of banks and financial institutions (Pham et al., 2021). Motivated by international agreements and increased foreign bank presence, the government has enacted reforms to boost efficiency and competitiveness, including privatizing state-owned banks. Domestic banks must respond by optimizing resource utilization, improving efficiency, or diversifying into fee-based revenue streams to remain competitive (Nguyen et al., 2018).

The SBV has recently introduced capitalization and prudential ratios aligned with the Basel framework. Consequently, commercial banks are mandated to adhere to the stipulated minimum charter capital prerequisites. This regulatory development carries significant ramifications for bank governance practices, focusing on bolstering the efficiency and stability of banks as they navigate the challenges of a fiercely competitive market environment.

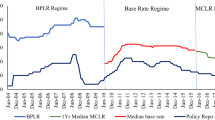

Monetary policy in Vietnam

Unlike some central banks, the SBV has a range of objectives in its monetary policy, including inflation control, economic growth, and macroeconomic stability, with no clear primary objective defined. To achieve these objectives, the SBV utilizes various monetary policy tools (Dang and Dang, 2020).

Since 2000, the SBV has introduced new monetary tools, including the base interest rate, policy rates, and open market operations, which differ from standard practices in other economies. The base interest rate, established to set lending rate limits for banks, has remained relatively stable since 2010. Policy rates, such as refinancing rates and rediscounting rates, have seen more frequent adjustments. Recently, the SBV has relied less on reserve requirements, favoring modern tools like open market operations and policy rates, maintaining a stable reserve requirement ratio since 2012 (Dang and Dang, 2020).

Literature review

This study relates to the literature strands analyzing the bank lending and risk-taking channels of monetary policy transmission. Under the proposition of the bank lending channel, monetary policy tightening causes a reduction in the volume of loanable funds and might contract lending activities if banks cannot offset decreased funds (Bernanke and Blinder, 1988). In more detail, monetary restriction raises the required reserves banks have to keep in the central bank, thus limiting the number of deposits to the availability of reserves (Kashyap and Stein, 1995). Alternatively, the bank lending channel functions via the effect of monetary policy on the external finance premium of banks as defined by their perceived balance sheet strength rather than via any shifts in deposits (Disyatat, 2011). The underlying mechanism is that monetary restriction may result in the deterioration of banks’ balance sheets in terms of leverage, asset quality, and risk perceptions. This mechanism raises the external finance premium of banks, making them suffer higher funding costs, which are ultimately passed on to bank lending activities. Additionally, lower interest rates amid monetary expansion alleviate the overall risk portfolio of banks, thereby inducing them to boost loan supply and release lending standards (Maddaloni and Peydró, 2011).

In the bank lending channel framework, the former literature has been interested in exploring the impact of moderating factors on the pass-through. The prior scholars usually reveal evidence that bank-specific characteristics can alter how bank lending responds to shifts in monetary policy stance. These moderating characteristics are popularly measured through bank size, capital, liquidity, and bank risk (Kashyap and Stein, 2000; Kishan and Opiela, 2006; Altunbas et al., 2010; Sáiz et al., 2018). In general, these works indicate the identical mechanism that weaker banks (i.e., banks that are smaller, less liquid, more poorly capitalized, or suffer more credit risk) are more responsive to monetary shocks due to their inability to approach alternative funding sources. Apart from these bank-specific characteristics, recent papers have paid attention to reforms and changes in the financial sector, such as prudential policies, market development, institutional quality, and shadow banking, in the working of the bank lending channel (Hussain and Bashir, 2019; Zhan et al., 2021; Fiador et al., 2022; Fabiani et al., 2022; Cheng and Wang, 2022). In this stream, mixed results have been shown. Taken together, while the existing literature has been investigating the conditional functioning of the monetary policy pass-through using various factors, limited research has been done to shed light on the “search-for-yield” incentives of banks thus far.

According to the bank risk-taking channel, monetary policy may influence bank risk-taking behavior through multiple routes. First, a variation in the interest-rate framework could alter the perception and tolerance of banks to risk. More precisely, lower interest rates in the event of monetary expansion increase investment valuations and subsequently banks’ revenues, thereby enhancing the risk-taking capacity of banks and inducing them to take more risks (Borio and Zhu, 2012). Second, monetary policy changes may encourage financial institutions to adjust their leverage, which modifies the pricing of risk and the degree of risk-taking at banks. Concretely, a cut in interest rates of safe assets reduces the opportunity costs of holding reserves, which are a fraction of banks’ deposits, thus promoting their demand for large leverage (Dell’Ariccia et al., 2014; Angeloni et al., 2015). This mechanism may cause banks to take on additional risks as well. Third, the bank risk-taking channel also works through communication policies. For example, a bad economic prospect might change the agents’ perceptions, leading to the view that the central bank would relax its monetary policy and cushion the economic uncertainty. Hence, banks predict such an insurance effect and are willing to take on more risk (Borio and Zhu, 2012).

Similar to the literature strand on the bank lending channel, abundant empirical research has confirmed the presence of the bank risk-taking channel in many countries, and its pass-through effect has been demonstrated to be conditional on multiple standard bank-specific factors. Many previous authors have revealed that lower interest rates substantially increase banks’ risk-taking, and this impact may differ with bank size, capitalization, off-balance sheet items, and bank diversification (Altunbas et al., 2014; Jiménez et al., 2014; Drakos et al., 2016; Dang and Huynh, 2022b). It should also be acknowledged that while the empirical evidence regarding the moderating functioning of monetary policy through the bank lending channel is rich, the available literature on the conditional link between monetary policy and bank risk is rather scarce.

Theoretically, there are strong reasons why we should expect the “search-for-yield” effect in the working behind the bank lending and bank risk-taking channels of monetary policy transmission. Simply put, a reduction in interest rates could interact with “sticky” return targets of banks to raise their risk tolerance, where the “search-for-yield” effect is defined (Rajan, 2006). More specifically, following the “Samuelson effect”, when interest rates remain lower at banks during monetary expansion, their revenues from loans tend to drop, while their interest costs from deposits do not decline to the same extent since banks’ portfolios primarily comprise demand and transaction deposits (Samuelson, 1945). These forces jointly narrow interest rate spreads and thus erode banks’ primary source of returns. Alternatively, a decrease in interest rates hampers bank profits because lending rate elasticity is larger than deposit rate elasticity (Hancock, 1985). Facing the profit-decreasing environment, however, banks’ return target may not change immediately, possibly because of lagged adjustments of shareholders’ expectations. Thus, this mechanism requires banks to allocate their investments toward “high-risk, high-return” assets (Dell’Ariccia et al., 2014) by granting more loans to riskier customers. Meanwhile, the compensation of bank managers is often associated with the amount above the return target. Hence, when decreased interest rates increase the likelihood of less compensation, managers’ incentive to establish a “search-for-yield” strategy may also proliferate (Deyoung et al., 2013).

Our study is related to two papers of Orzechowski (2017) and Dang and Dang (2020). Orzechowski (2017) explores the impact of monetary policy on loan growth at different groups of profitable banks. The author documents that monetary policy exerts a slightly larger negative impact on real estate loans at banks with above-average profit rates than those with below-average profit rates. In another vein, Dang and Dang (2020) investigate the working of the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission, particularly highlighting the heterogeneity across different banks with respect to their performance. Because they do not confirm the bank risk-taking channel when approaching credit risks and monetary interest rates, they can only offer evidence that the link between monetary policy and bank risk-taking is less pronounced at more profitable and efficient banks. In general, these two papers do not offer any evidence supporting the underlying mechanism that banks’ incentives to search for yield work in monetary policy transmission. Furthermore, only using the level measurements of bank return (Dang and Dang, 2020) or dividing banks into two groups using their relative profitability benchmark (above or below the average profit ratio) (Orzechowski, 2017), while analyzing a single banking channel (the bank lending channel or the bank risk-taking channel), is not sufficient to verify the “search-for-yield” incentives of banks thoroughly. Our paper expands these previous studies by incorporating multiple key channels of monetary policy transmission and a series of effective measures for evaluating banks’ search-for-yield incentives.

Data and methodology

Data

We collect data on commercial banks in Vietnam during the 2007–2019 period from their annual financial reports. To warrant comparability and minimize any potential bias, other entities, such as policy banks or commercial banks that are subject to compulsory acquisition and special control by the SBV, are excluded from our sample due to significant differences in nature, business scope, and restraints. Our sample forms an unbalanced panel from 31 commercial banks (with observations as shown in Table 1), accounting for more than 90% of the total assets in the Vietnamese banking sector. We then winsorize the bank-level data that lie above the 97.5th percentile and below the 2.5th percentile to wipe out the influences of extreme outliers. The monetary policy indicators and macroeconomic data are sourced from the SBV database (refinancing rates and rediscounting rates), the World Development Indicators of the World Bank (inflation and GDP growth), and the Vietstock database (VNindex), respectively.

Regression models and variables

This study empirically investigates whether the functioning of the bank lending and risk-taking channels of monetary policy is attributable to the “search-for-yield” effect. To this end, we employ the model specified as follows:

where i and t denote bank and time dimensions, respectively. Y stands for the bank lending and risk-taking variables separately, captured by the percentage growth of bank loans and the natural logarithm of the Z-score index, respectively. The one-period lag of the dependent variable is included as a regressor in the right-hand side of the equation to adopt the dynamic nature of lending and risk-taking behaviors. MPI is the monetary policy indicators. Search for yield is the proxy that reflects the bank incentives of searching for yield. MPI × Search for yield is intended to assess the conditional role of “search-for-yield” incentives in the impacts of monetary policy shocks on bank lending and bank risk. Z contains bank-level control variables, X consists of macroeconomic control factors, and εi,t is the error term. To mitigate the endogeneity problem and further imply that bank output takes some time to react to the movements in internal and external environments, we use the lagged values of all independent variables.

Our dynamic panel model is estimated using the two-step system GMM regression (Blundell and Bond, 1998), which is best suited to deal with endogeneity concerns as well as offer efficient and unbiased estimates. We further apply instrument collapse options to restrict the problem of “too many instruments” (Roodman, 2009) and rely on some necessary tests to guarantee the validity of the GMM estimator (the Hansen test of valid instruments and the AR(1)/AR(2) tests for the first- and second-order serial correlation).

While the growth rate of bank loans has been widely accepted in the bank lending channel literature as a straightforward lending measure, the use of the Z-score index for bank risk-taking in this paper needs to be explained in further detail. In testing the linkage between monetary policy and bank risk, the good choice to measure bank risk-taking behavior is not obvious. Based on this fact, we decide to approach the Z-score index, which is commonly employed to gauge the financial stability, insolvency, or overall riskiness of banks (Beck et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017; Brana et al., 2019; Phan et al., 2021), rather than focusing on any specific type of risk that a bank could face (e.g., credit risk or liquidity risk). The formula to calculate the Z-score is as follows:

where ROA is the return-on-asset ratio, Capital is the equity-to-asset ratio, and σ(ROA) is the standard deviation of ROA using the three-year rolling time window. The lower the Z-score index, the more (less) the overall riskiness (the financial stability). In line with the former literature, we utilize the natural logarithm of (1 + Z-score) in regression analysis to smooth greater values and evade the truncation of the Z-score index at zero (Beck et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2017).

Consistent with a practice usually adopted in early papers, we select short-term interest rates as monetary policy indicators in our study. Concretely, we employ two types of policy rates, namely refinancing rates and rediscounting rates, to gauge the SBV’s monetary policy stance (Dang and Huynh, 2022a). As the lender of last resort, the SBV charges refinancing rates for short-term loans and rediscounting rates for the discounts of valuable papers while making transactions with the commercial banking system. Here, our selection of two policy rates is also motivated by the fact that other monetary tools, such as the reserve requirement and base interest rates, have remained constant for extended periods in Vietnam. Overall, given the choice of our dependent and independent variables of key interest, the estimate on monetary policy indicators is expected to be negative (in the model of bank loan growth) to justify the bank lending channel and positive (in the model of Z-score) to verify the bank risk-taking channel.

We now turn to the construction of our “search for yield” variables. Following Wu et al. (2020), we proxy banks’ search-for-yield incentives by computing the difference between ROA/ROE and its past-three-year average (denoted as SFYroa and SFYroe, respectively). The complementary usage of different “search-for-yield” measures is helpful in strengthening the robustness of our findings. Given that banks’ business target frequently converges to maximize profitability, they may be motivated to search for yield more (less) aggressively if their profit is further below (above) its past level. These measures delineating banks’ (dis)incentive of the “search-for-yield” strategy are subsequently subjected to interaction with monetary policy. Should a bank exhibit a heightened proclivity for the pursuit of yield, as evidenced by diminished values of the SFYroa/SFYroe variables, particularly during a period of monetary policy expansion, it is expected that such a bank will witness more pronounced escalations in its lending activities and proclivity for risk-taking compared to its peer institutions, driven by the imperative of achieving targeted profitability. Alternatively, the impact of monetary policy on bank lending/banking risk should be amplified with a decrease in the values of SFYroa/SFYroe variables. In this context, we expect (i) the estimate on the interaction term to be positive, opposite to the standalone monetary policy variables in the model of loan growth, and (ii) the estimate on the interaction term to be negative, opposite to the standalone monetary policy variables in the model of Z-score.

Our study belongs to a well-established strand of literature on the determinants of bank lending and risk-taking behaviors (Ibrahim, 2016; Kapan and Minoiu, 2018; Dang and Huynh, 2022a; Jiang and Yuan, 2022). Apart from monetary policy interest rates and search-for-yield incentives, how banks are susceptible to loan growth and risk profiles has been widely found to be defined by various bank-specific factors, including bank size, capitalization, and liquidity positions. To better identify the impacts of monetary policy on bank lending and bank risk, we control for these likely relevant variables. Besides, we also introduce three macroeconomic factors as control variables in our regression models. More precisely, we allow for the presence of the stock market, inflation, and economic cycles, which help distinguish the demand-side effect from the supply-side one. For the specific calculations of these control variables, please see our presentation in Table 1.

Results

Preliminary analysis

We summarize the definitions of employed variables and their key descriptive statistics in Table 1. The mean value of the bank loan growth in Vietnam is 29.533%, and its standard deviation is 29.671%, implying a high speed of expansion and vast differentiation in the lending activities across banks in the research period. The lnZscore variable is centered on the mean value of 3.951 and the standard deviation of 0.875, also displaying a considerable dispersion of banks in terms of their overall riskiness. Significantly, the large standard deviations and the broad ranges of “search for yield” variables strongly suggest a sizable variation in the incentives of improving returns in the banking system. For monetary policy proxies, the statistical distribution for two main variables signifies certain adjustments in policy rates in the period under study.

We also exhibit in Table 2 the pairwise correlation coefficients among all employed variables. Some interesting patterns have emerged. We first realize that the correlation coefficients between the loan growth and monetary policy indicators are negative, while those between the bank stability and interest rates are positive. These results lend support to the existence of the bank lending and risk-taking channels of monetary policy transmission. Besides, the pairwise correlation coefficients among independent variables identify that serious multicollinearity could not be a concern as long as we pay close attention to the exceptionally large correlation coefficient between the inflation rate and interest rates. Hence, given that monetary policy is our main concentration for this analysis, we exclude the inflation variable in the subsequent regression model.

We will proceed to the key research stage for regression analysis. Before looking into the regression coefficients of paramount interest, we need to observe the results of diagnostic tests to justify the consistency and appropriateness of the dynamic GMM regression. Accordingly, for the regression results reported subsequently, we all find that: (i) bank behavior is significantly dependent on its past conditions, thus highlighting the dynamic nature; (ii) the Hansen test of over-identifying restrictions suggests the jointly valid instruments; (iii) and the AR(1)/AR(2) tests indicate the first- but no second-order serial correlation in the residuals. Overall, we could gain confidence with all the regression results obtained in this paper.

The bank lending channel

We report the estimation results of our loan growth model in Table 3, using both refinancing rates (columns 1–2) and rediscounting rates (columns 3–4) as monetary policy variables. The regression coefficients on the standalone monetary policy indicators are consistently significant and negative, thus strongly indicating the presence of the bank lending channel of monetary policy pass-through that has been well witnessed in the existing literature (Sáiz et al., 2018; Hussain and Bashir, 2019; Zhan et al., 2021; Fiador et al., 2022; Fabiani et al., 2022; Cheng and Wang, 2022). In other words, a relaxed monetary policy increases the lending activities of banks.

In line with our expectation, the coefficients on the interaction term of monetary policy interest rates and “search for yield” variables are positive and statistically significant in most regressions. Overall, our results are robust across two types of policy rates and multiple ways of capturing the extent to which banks try to search for yield, thus firmly revealing an augmented lending impact of monetary policy changes for banks with more substantial incentives for improving their profits. The supply-side effect we are exploring is at work here; concretely, if interest rates remain lower amid monetary policy easing, banks are likely to expand their lending activities more aggressively to offset their reduced revenues (Rajan, 2006).

Our findings also highlight the economic significance. For example, a one percentage point decrease in refinancing rates is translated into an increase of 2.188% in the expansion of bank loans (using the coefficient of column 1 in Table 3). Looking at the interaction term Refinancing rates*SFYroa, a decrease of one standard deviation in the gap between the return-on-asset ratio and its past-three-year average (i.e., more “search-for-yield” incentives) may raise the effects of refinancing rates on the loan growth rate by 0.290% (~0.460 × 0.630, given the change of one percentage point in refinancing rates).

The bank risk-taking channel

We next examine the effective mechanism behind the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy. In the equation using the Z-score index as the dependent variable, a variety of monetary policy indicators and search for yield variables are all employed separately. It should be noted that in the case of the Z-score dependent variable, we replace the capitalization variable with business models (obtained by the ratio of non-interest income to total operating income) to limit the likelihood of spurious regressions since the capital factor is a key component in the computation of the Z-score index.Footnote 1 We report our estimation results in Table 4.

The coefficients on different standalone monetary policy interest rates display positive signs and are statistically significant in all columns. These results imply that, ceteris paribus, the overall riskiness of banks tends to rise when interest rates decrease, lending support to the proposition of the bank risk-taking channel (Borio and Zhu, 2012). When the central bank reduces its policy rates in the event of monetary policy expansion, the financial stability of banks deteriorates. Quantitatively, the magnitude of coefficients shows the economic plausibility of our findings. Taking column 2 of Table 4 as an example, we infer that a decrease of one percentage point in rediscounting rates causes banks to increase their overall riskiness measured by the Z-score index by 0.039%.

Most interaction terms are found to be significantly negative, indicating a strengthening effect of “search-for-yield” incentives on the link between monetary policy and bank stability. For the statistically insignificant interaction term (column 4), its coefficient still exhibits a negative sign. Hence, the detrimental impact associated with monetary policy easing is attributable to the search-for-yield incentive of banks (Rajan, 2006). Although many works have interpreted the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy using this bank incentive, our study is the first to offer direct evidence indicating that this search-for-yield strategy works in the banking sector. In response to a policy rate cut, more incentivized banks tend to increase their risk-taking to a larger extent than their less incentivized counterparts. Our patterns are economically significant as well.

The novel bank liquidity creation channel: is the search-for-yield incentive still at work?

In this paper, we go a step further and analyze the association between the interaction term of monetary policy and search-for-yield incentives with bank liquidity creation. Creating liquidity is the banks’ core function in the economy. On the balance sheet, banks could create liquidity by financing illiquid assets with liquid liabilities; off the balance sheet, banks could also create liquidity via loan commitments and similar claims to liquid funds. While creating liquidity, banks decrease their own liquidity (Berger and Bouwman, 2009). Interestingly, bank liquidity creation is viewed as a broader output measure than bank lending (Berger and Bouwman, 2009).

Theoretically, bank liquidity creation is anticipated to be driven by the shocks in monetary policy in multiple routes. On the balance sheet, banks might increase their loans and deposits as a result of monetary policy expansion. Besides, a decrease in interest rates raises the present value of fixed-rate loans in banks’ portfolios, enhancing their net worth and boosting bank loan supply (see the bank lending channel elaborated earlier). Off the balance sheet, banks might provide more commitments due to the greater availability of loanable funds and a shrinkage in the cost of these funds (Kashyap et al., 2002). Empirically, compared to bank lending or risk-taking behaviors, the evidence of the effect of monetary policy on bank liquidity creation is scarce. In particular, we are aware of a few papers that empirically explore the monetary policy/bank liquidity creation link (Berger and Bouwman, 2017; Dang and Dang, 2021; Dang and Huynh, 2022a).

In the seminal paper, Berger and Bouwman (2017) document how bank liquidity creation responds to monetary policy adjustments and propose the so-called “bank liquidity creation channel” of monetary policy transmission. Nevertheless, their evidence is weak (the link is found statistically significant but economically diminutive at small banks) and mixed (an ambiguous conclusion is reached for medium and large banks). Recently, Dang and Dang (2021) and Dang and Huynh (2022a) confirm the novel banking channel suggested by Berger and Bouwman (2017) and also add to this work by the conditional roles of multiple bank-specific characteristics (e.g., bank size, capital structure, and liquidity position) in the bank liquidity creation channel. However, as we argued thoroughly in this paper, the use of such bank-specific characteristics is not adequate to shed light on the mechanism behind the transmission; in more detail, the hypothesis of the “search-for-yield” incentives is not taken into account.

To confirm and expand the literature on the link between monetary policy and bank liquidity creation, we now build up appropriate liquidity creation measures using the innovation of Berger and Bouwman (2009) and the modification of Dang and Dang (2021) for Vietnamese banks.Footnote 2 As suggested by Berger and Bouwman (2009), we utilize two versions of liquidity creation measures, including “cat fat” and “cat nonfat” for our analysis, which include and exclude off-balance-sheet components, respectively. The growth rate of these two liquidity creation measures is grasped before entering the regression process. We conduct the estimation in the equation of liquidity creation variables using the econometric design similar to that applied previously for the model of bank loan growth. We report all estimation results in Tables 5 and 6.

The coefficients on monetary policy variables are statistically significant and negative in all regressions, thereby justifying the working of the bank liquidity creation channel (Berger and Bouwman, 2017; Dang and Dang, 2021; Dang and Huynh, 2022a). Turning to our main interest, the results from the interaction term indicate that demotivated banks appear to undermine the effectiveness of monetary policy in the bank liquidity creation channel, as we observe that the interaction term between monetary policy and “search for yield” variables is shown consistently positive in most estimations. The two liquidity creation measures provide similar results with respect to “search-for-yield” incentives in monetary policy transmission as we consider the aspects of bank lending and risk-taking behaviors. The underlying mechanism demonstrated is that lower interest rates squeeze banks’ profitability and thus induce them to search for better yields more aggressively. For the economic significance, the quantitative impacts observed in this case are also salient. Using the estimation result reported in column 2 of Table 5 as an example, we realize that as refinancing rates drop by one percentage point, the total bank liquidity creation captured by the “cat fat” measure tends to correspondingly increase by 4.006%, which might be amplified by about 2.809% (~0.621 × 4.523) when the “search-for-yield” incentives surge by one standard deviation as measured using the SFYroe variable.

Robustness checks

We now perform various checks to determine the robustness of our results. We first replace our policy rates by using the average short-term lending rates, which are widely used in prior literature and are especially perceived as an excellent indicator of monetary policy stance in Vietnam (Dang and Huynh, 2022a). For the data source, we collect the average short-term lending rates from the International Financial Statistics of the International Monetary Fund. Next, we change our econometric methodologies by adjusting the economic model and employing an alternative method. Accordingly, we approach the static model with fixed effects, as suggested by the Hausman test. Inspired by Hoechle (2007), we run regressions with corrected Driscoll–Kraay standard errors to tackle the issues of autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity, and cross-sectional dependence. We combine and report estimation results by robustness checks, as in Tables 7–9.

Additionally, for the individual case of the bank risk-taking regression, we replace the Z-score index with an alternative version as the dependent variable. To this end, we calculate the standard deviation of ROA (i.e., the σ(ROA) component in the equation of the Z-score index) for the entire period under research instead of using the three-year rolling time window as previously. In this situation, not using a rolling window leads to a substantial increase in the number of observations for our bank risk variable. Furthermore, our dataset includes a potential structural break caused by the global financial crisis (2007–2009) that can distort the functioning of the monetary policy pass-through. Hence, we should conduct a subsample analysis around this financial crisis to examine whether the results after the financial turmoil remain the same. We display subsample checks in the function of the alternative Z-score index in Table 10.Footnote 3

Overall, across all robustness checks in Tables 7–10, the signs and significance of coefficients on monetary policy still confirm the existence of the bank lending, bank risk-taking, and bank liquidity creation of monetary policy. Further importantly, the re-estimated results on the interaction terms remain identical to those previously obtained, albeit the statistical significance has slightly diminished at some regressions. We again gain solid evidence showing that the association between monetary policy and bank output is driven by force from the supply side; in particular, the search-for-yield incentive is still at work. In sum, one joint mechanism through which monetary policy drives bank output, broken down into bank lending, bank risk-taking, and bank liquidity creation, is through changes in the “search-for-yield” incentives that arise from the deviation of interest rates from banks’ target returns.

Conclusions

This paper explores the possible mechanism behind the monetary policy and bank output nexus in Vietnam during 2007–2019. We empirically perform this task by using various measures that capture the bank incentives of searching for yield and then adding them to the regression model to estimate the interactive effects of monetary policy with these measures of interest. Our results consistently show that the relationship between monetary policy and bank output, as discussed in the dimensions of bank lending, bank risk-taking, and bank liquidity creation, is more pronounced for banks with stronger incentives to search for yield. More precisely, our innovation in this paper is to answer that banks with stronger incentives to search for yield, as a result of substantial yield reductions amid monetary policy easing through lower interest rates, tend to (i) expand lending activities, (ii) increase the risk profiles, and (iii) create more liquidity to the real economy. Banks are likely to move toward “more pain, more gain” projects if their profits are decelerated. Our finding is robust against a series of alternative monetary policy indicators, different bank output measures, multiple “search-for-yield” proxies, and substitute econometric methodologies.

Overall, our findings shed light on the underlying monetary policy transmission mechanism and suggest some important implications. As the link between monetary policy and bank output is found due to banks’ decisions, monetary authorities need to take these effects on the pass-through mechanism into account when implementing their monetary policy. The potency of the bank lending/liquidity creation channels may be limited if banks are not provided with incentives to search for yield, which simultaneously weakens the detrimental consequences of expansionary monetary policy on banking stability, as observed in the bank risk-taking channel. We claim that banks’ search-for-yield incentives must be thoroughly regarded, together with other standard bank-specific characteristics, when examining the functioning of the banking channels of monetary policy transmission.

This study’s scope is confined to a singular market, which in turn may limit the broader applicability of its contributions. Hence, future research endeavors should extend our findings to other single markets and/or cross-market contexts. Subsequent findings may either corroborate or countermand our present results, thereby fostering an enriched comprehension of the prevailing subject matter pertaining to the transmission mechanism of monetary policy vis-à-vis the search-for-yield dynamics. Further, while we offer empirical evidence in support of the supply-side effect in the functioning of multiple key banking channels of monetary policy, i.e., the bank incentive of “search for yield”, we leave a more rigorous investigation of the demand-side mechanism to future studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Notes

We also eliminated the bank capital variable completely without using the variable substitution technique; then, we still achieved identical regression results as those reported.

For the specific step-by-step procedures in item classification, weight assignment, and calculation of liquidity creation for the banking system in Vietnam, please refer to the work of Dang and Dang (2021). The descriptive statistics of our two liquidity creation variables are also exhibited in Table 1.

The bank lending channel analysis for the subsample excluding the financial crisis period of 2007–2009 also provides robust results. For brevity, we only present a certain set of repeated estimates in the paper. Other estimation results are available upon any request.

References

Altunbas Y, Gambacorta L, Marques-Ibanez D (2012) Do bank characteristics influence the effect of monetary policy on bank risk? Econ Lett 117:220–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.04.106

Altunbas Y, Gambacorta L, Marques-Ibanez D (2010) Bank risk and monetary policy. J Financ Stab 6:121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2009.07.001

Altunbas Y, Gambacorta L, Marques-Ibanez D (2014) Does monetary policy affect bank risk? Int J Cent Bank 34:95–135

Angeloni I, Faia E, Lo Duca M (2015) Monetary policy and risk taking. J Econ Dyn Control 52:285–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2014.12.001

Beck T, De Jonghe O, Schepens G (2013) Bank competition and stability: cross-country heterogeneity. J Financ Intermediation 22:218–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2012.07.001

Berger AN, Bouwman CHS (2009) Bank liquidity creation. Rev Financ Stud 22:3779–3837. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn104

Berger AN, Bouwman CHS (2017) Bank liquidity creation, monetary policy, and financial crises. J Financ Stab 30:139–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2017.05.001

Bernanke BS, Blinder AS (1988) Credit, money, and aggregate demand. Am Econ Rev 78:435–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-2510(11)70055-9

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87:115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

Borio C, Zhu H (2012) Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism? J Financ Stab 8:236–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2011.12.003

Brana S, Campmas A, Lapteacru I (2019) (Un)Conventional monetary policy and bank risk-taking: a nonlinear relationship Econ Model 81:576–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.07.005

Chen M, Wu J, Jeon BN, Wang R (2017) Monetary policy and bank risk-taking: evidence from emerging economies. Emerg Mark Rev 31:116–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2017.04.001

Cheng X, Wang Y (2022) Shadow banking and the bank lending channel of monetary policy in China. J Int Money Financ 128. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JIMONFIN.2022.102710

Dang VD, Dang VC (2020) The conditioning role of performance on the bank risk-taking channel of monetary policy: evidence from a multiple-tool regime. Res Int Bus Financ 54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101301

Dang VD, Dang VC (2021) How do bank characteristics affect the bank liquidity creation channel of monetary policy? Financ Res Lett 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.101984

Dang VD, Huynh J (2022a) Bank funding, market power, and the bank liquidity creation channel of monetary policy. Res Int Bus Financ 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RIBAF.2021.101531

Dang VD, Huynh J (2023) How does uncertainty drive the bank lending channel of monetary policy? J Asia Pacific Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2023.2196883

Dang VD, Huynh J (2022b) Monetary policy and bank performance: the role of business models. North Am J Econ Financ 59. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NAJEF.2021.101602

Dell’Ariccia G, Laeven L, Marquez R (2014) Real interest rates, leverage, and bank risk-taking. J Econ Theory 149:65–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2013.06.002

Deyoung R, Peng EY, Yan M (2013) Executive compensation and business policy choices at U.S. commercial banks. J Financ Quant Anal 48:165–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109012000646

Disyatat P (2011) The bank lending channel revisited. J Money Credit Bank 43:711–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2011.00394.x

Drakos AA, Kouretas GP, Tsoumas C (2016) Ownership, interest rates and bank risk-taking in Central and Eastern European countries. Int Rev Financ Anal 45:308–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2014.08.004

Fabiani A, Piñeros ML, Peydró J-L, Soto PE (2022) Capital controls, domestic macroprudential policy and the bank lending channel of monetary policy. J Int Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JINTECO.2022.103677

Fiador V, Sarpong-Kumankoma E, Karikari NK (2022) Monetary policy effectiveness in Africa: the role of financial development and institutional quality. J Financ Regul Compliance. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-03-2021-0024/FULL/XML

Hancock D (1985) Bank profitability, interest rates, and monetary policy. J Money Credit Bank 17:189–202. https://doi.org/10.2307/1992333

Hoechle D (2007) Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. Stata J 7:281–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x0700700301

Hussain M, Bashir U (2019) Impact of monetary policy on bank lending: does market structure matter? Int Econ J 33:620–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2019.1668820

Ibrahim MH (2016) Business cycle and bank lending procyclicality in a dual banking system. Econ Model 55:127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECONMOD.2016.01.013

Jiang H, Yuan C (2022) Monetary policy, capital regulation and bank risk-taking: evidence from China. J Asian Econ 82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ASIECO.2022.101512

Jiménez G, Ongena S, Peydró J, Saurina J (2014) Hazardous times for monetary policy: what do twenty-three million bank loans say about the effects of monetary policy on credit risk-taking? Econometrica 82:463–505. https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta10104

Kapan T, Minoiu C (2018) Balance sheet strength and bank lending: evidence from the global financial crisis. J Bank Financ 92:35–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBANKFIN.2018.04.011

Kashyap AK, Rajan R, Stein JC (2002) Banks as liquidity providers: an explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking. J Finance 57:33–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00415

Kashyap AK, Stein JC (1995) The impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets. Carnegie-Rochester Conf Ser Public Policy 42:151–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2231(95)00032-U

Kashyap AK, Stein JC (2000) What do a million observations on banks say about the transmission of monetary policy? Am Econ Rev 90:407–428. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.3.407

Kishan RP, Opiela TP (2006) Bank capital and loan asymmetry in the transmission of monetary policy. J Bank Financ 30:259–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.05.002

Maddaloni A, Peydró JL (2011) Bank risk-taking, securitization, supervision, and low interest rates: evidence from the Euro-area and the U.S. lending standards. Rev Financ Stud 24:2121–2165. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhr015

Nguyen TN, Stewart C, Matousek R (2018) Market structure in the Vietnamese banking system: a non-structural approach. J Financ Regul Compliance 26:103–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-03-2016-0024

Orzechowski PE (2017) Bank profits, loan activity, and monetary policy: evidence from the FDIC’s Historical Statistics on Banking. Rev Financ Econ 33:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rfe.2016.11.002

Pham HST, Le T, Nguyen LQT (2021) Monetary policy and bank liquidity creation: does bank size matter? Int Econ J 35:205–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2021.1901762

Phan DHB, Iyke BN, Sharma SS, Affandi Y (2021) Economic policy uncertainty and financial stability–is there a relation? Econ Model 94:1018–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.02.042

Rajan RG (2006) Has finance made the world riskier? Eur Financ Manag 12:499–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-036X.2006.00330.x

Roodman D (2009) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J 9:86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x0900900106

Sáiz MC, Azofra SS, Olmo BT, Gutiérrez CL (2018) A new approach to the analysis of monetary policy transmission through bank capital. Financ Res Lett 24:199–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2017.07.021

Samuelson PA (1945) The effect of interest rate increases on the banking system. Am Econ Rev 35:16–27

Su DT, Neil H, Nguyen PC (2020) Public spending, public governance and economic growth at the Vietnamese provincial level: a disaggregate analysis. Econ Syst 44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOSYS.2020.100780

Varlik S, Berument MH (2017) Multiple policy interest rates and economic performance in a multiple monetary-policy-tool environment. Int Rev Econ Financ 52:107–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2017.10.004

Vo XV (2016) Finance in Vietnam-an overview. Afro-Asian J Financ Acc 6:202–209. https://doi.org/10.1504/AAJFA.2016.079311

Wu J, Yao Y, Chen M, Jeon BN (2020) Economic uncertainty and bank risk: evidence from emerging economies. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2020.101242

Zhan S, Tang Y, Li S, et al (2021) How does the money market development impact the bank lending channel of emerging countries? A case from China. North Am J Econ Financ 57: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2021.101381

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH is solely responsible for this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huynh, J. The monetary policy pass-through mechanism: Is the search-for-yield incentive at work?. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 886 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02425-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02425-z