Abstract

Knowledge mobilisation can be achieved through various routes. This can include immersive, in-person time spent in a different workplace with people from other disciplines or sub-sectors. By doing so participants mobilise and exchange knowledge through observing the dynamics of a different workplace; by learning directly from others with different expertise and/or through sharing their own expertise. We have called this form of knowledge exchange ‘Workplace-based Knowledge Exchange Programmes’ (WKEPs) and have focused on their role in the health and care sector because of the importance of knowledge mobilisation in this field yet their relatively low profile in the literature. This study explores the main characteristics of WKEPs among academics, providers, and policymakers in the health and care sector in the United Kingdom (UK) through a scoping review and mapping exercise. We systematically identified 147 academic articles (between 2010 and 2022) and 74 websites which offered WKEPs as part of, or all of, their knowledge mobilisation activities (between 2020 and 2022). Characteristics were grouped into structures, processes, and outcomes. WKEPs lasted between one day and five years and were mostly uni-directional. Exchange ambitions varied, aiming to benefit both the participants and their working environments. They commonly aimed to build networks or collaborations, improve understanding of another field and bring back knowledge to their employer, as well as improve leadership and management skills. Almost all programmes were for healthcare providers and academics, rather than social care providers or policymakers. In-person WKEP activities could be categorised into four domains: ‘job shadowing’, ‘work placements’, ‘project-based collaborations’, and ‘secondments’. The aims of many of the WKEPs were not clearly described and formal evaluations were rare. We used the findings of this study to develop a framework to describe WKEP activities. We suggest the use of common language for these activities to aid participation and research, as well as recommending principles for the comprehensive advertising of WKEPs and reporting of experiences after participation in WKEPs. We recommend the establishment of an online repository to improve access to WKEPs. These resources are necessary to strengthen understanding and the effectiveness of WKEPs as a mechanism for knowledge mobilisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many higher education providers and research funders in the UK have objectives around knowledge exchange and mobilisation. In the context of the health and care field, knowledge mobilisation is defined as ‘the sharing of knowledge between communities to catalyse change, which can include research producers pushing out their findings, research users seeking out health research, but also the co-production or co-creation of knowledge’ (NIHRtv, 2022). For many in the field, ‘knowledge’ is multi-faceted, including research evidence, but also technical knowledge (including practical skills, experiences and expertise) and practical wisdom (including professional judgments, values and beliefs) (Ward, 2017). These definitions have been derived over decades in a rich literature base, much of which has been focused on understanding what happens once knowledge (or evidence) has been brought into practice from an implementation science discipline perspective (c.f., (Harvey and Kitson, 2016; Lynch et al. 2018; Nilsen, 2015)). The literature also includes numerous evaluations of knowledge exchange interventions, demonstrating the diversity of approaches to knowledge exchange, such as:

-

-

‘embedded researchers’/‘researchers in residence’ who inform local care practices by drawing on research knowledge (Marshall et al. 2014; Ward et al. 2021),

-

-

‘knowledge brokers’/‘boundary spanners’ who bring new knowledge into an organisation by building relationships with outside organisations or providing skills training (Nasir et al. 2013),

-

-

researchers being seconded into policy organisations to encourage evidence use in policymaking (O’Donoughue Jenkins and Anstey, 2017; Uneke et al. 2017),

-

-

simultaneous secondments and the creation of an embedded team of researchers and local policymakers (Wye et al. 2020), and

-

-

funded and facilitated long-term partnerships between academia and practice to bridge the gap between evidence and policy (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2015).

Frameworks have also been developed from systematic mapping exercises to help categorise interventions in the health and care field. For example, Ward (2017) provided a conceptual framework offering probes and categorical responses to knowledge mobilisers when analysing models, including ‘Why mobilise knowledge?’, ‘Whose knowledge is being mobilised?’, ‘What type of knowledge?’, ‘How is knowledge mobilised?’. The mutually exclusive categories describing why knowledge could be mobilised included: to develop local solutions to practice-based problems; to develop new policies, programmes and/or recommendations; to adopt/implement clearly defined practices and policies; to change practices and behaviours; and to produce useful research/scientific knowledge. These frameworks have progressed the way that knowledge mobilisation activities are framed and discussed by researchers, as well as helped confirm conceptualisations of what ‘counts’ as evidence or knowledge for practice and policy, building on previous suggestions for the inclusion of experiential and practical knowledge (Oliver et al. 2019, 2014).

Despite the breadth and depth of the literature on knowledge mobilisation and exchange in health and care, we argue that gaps remain. While the evaluations of interventions have provided helpful information about individual knowledge exchange activities, they provide little insight into how to compare knowledge exchange interventions. Furthermore, while the existing frameworks compare activities, they appear to be targeted at people who self-identify as knowledge mobilisers and do not encourage the categorisation of some of the more practical details involved in running or participating in a knowledge exchange intervention. For example, we were aware of a long-standing knowledge exchange programme that involves a cohort of hospital-based doctors and managers working through a range of activities, including shadowing, group-based learning, and quality improvement projects. Collectively, these activities aimed to improve relationships between participants, helping them to better understand each other’s daily challenges in order to find local solutions and ultimately improve the patient care provided in the hospital (Klaber et al. 2011). Using Ward’s (2017) framework, we were unable to articulate a main aim, as the programme aimed to develop local solutions to practice-based problems and new policies, change practices and behaviours, and produce useful research—as well as build relationships enabling better care, which according to this framework, is not an end goal. Another example of an ongoing knowledge exchange programme we believed needed an expanded description rooted in practical information was the Harkness Fellowship, which involves a cohort of mid-career researchers, policymakers, and care providers moving to the United States for 12 months to build methodological research skills, develop contacts, and opportunities for collaboration on research that will improve health systems.Footnote 1 While the main goal is to produce useful research, the programme was also meant to develop the Fellow in a professional capacity through research skills and contacts.

Thus, with the ambition to increase awareness of and access to immersive workplace-based knowledge exchange concepts and opportunities, we carried out a scoping study to map their characteristics and relationships in an applied conceptual framework. We decided to call the immersive, workplace-based opportunities we were interested in ‘workplace-based knowledge exchange programmes’ (WKEPs) and were guided by the research question: What are the characteristics of workplace-based knowledge exchange programmes in the health and care field in the UK as described: (i) in the international academic literature; and (ii) on their websites and webpages?

Methods

This scoping study involved a review of the international academic literature, a mapping exercise of the WKEP opportunities in the UK advertised online, and interviews with WKEP beneficiaries. This article examines the first two data sources, and the interview data are reported separately (Kumpunen et al. 2023). We chose to undertake a scoping review because of the exploratory nature of our research questions, which aimed to describe the key characteristics of WKEPs and knowledge gaps (Peters et al. 2022). Mapping exercises are known to be helpful in revealing the organisation and structure of a field’s scholarship and providing direction for its growth and sustainability (Farley-Ripple et al. 2020). We followed guidance and commentary on developing and reporting scoping reviews (Colquhoun et al. 2014; Peters et al. 2015; Tricco et al. 2018). The scoping review and mapping exercise involved five stages carried out in parallel for the two data sets: (1) defining research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies/exchange programmes, (3) selecting texts/programmes, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al. 2010).

Identifying relevant papers/exchange programmes

For the scoping review, we searched five electronic databases, MEDLINE, Embase, ERIC, OpenGrey, HMIC and Google Scholar, using a search strategy adapted for each database (available in Supplementary File 1). The search strategy was piloted to identify volumes of results and check that key papers had been identified. The electronic search strategy was reviewed by a clinical librarian to ensure that all search terms and sources were captured and that the search strategy was optimal for the review questions.

For the mapping exercise, we used five approaches to identify programmes summarised in Supplementary File 1, which included: (i) running site-specific searches using Google advanced search functionality (e.g., Academy of Medical Sciences, Medical Research Council); (ii) searching Google using the scoping review terms; (iii) using simplified derivatives of the scoping review search terms in Google; (iv) using single search terms (intended to mimic how applicants might search) in Google; and (v) collecting programme names using word of mouth recommendations from interviewees in our wider scoping project.

Selecting articles and online advertisements

Exchanges were included if they were for employed adults working in the health and care field as a health or care provider (including clinicians and non-clinicians), in academia (in any role), or as a policymaker (in any role), and involved at least one uni- or bi-directional in-person visit to a peer’s workplace. Exchanges were included regardless of whether they involved reflection, a key component of experiential learning (Lewis and Williams, 1994) and a concept from the education literature we were interested in exploring for its role in knowledge exchanges in health and care. Exchanges were excluded if they were intended for secondary school or undergraduate degree students (e.g., student placements, internships, or ‘first job’ placements), as these are commonplace in the health and care sector, and we were seeking to understand the role of exchanges following training. Similarly, exchanges were excluded if their primary purpose was to obtain a qualification or degree (e.g., postgraduate medical training, clinical doctoral fellowships) or a job (e.g., retraining programmes with work placements). We also excluded international clinical placements where the NHS offers temporary training opportunities to overseas clinicians (e.g., Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Medical Training InitiativeFootnote 2). Models that involved exchanges for example through action learning sets, but that did not involve a period of time embedded/physically immersed in another workplace (e.g., Digital Pioneer FellowshipsFootnote 3) or interdisciplinary / inter-policy networks (e.g., Catapult NetworkFootnote 4 or Sciana – The Health Leaders NetworkFootnote 5) were excluded. However, it is worth noting that while these programmes were out of scope for this study, they may share characteristics with the included types of exchanges. For the scoping review, we sought to include all English language papers found in the academic literature including opinion based articles, case reports, observational and experimental research, as well as literature reviews. The scoping review was international in searches, but we analysed papers where at least one participant or component of the exchange was carried out in the UK. The mapping exercise was limited to UK-based opportunities or those which targeted UK residents.

The scoping review was searched from 1 January 2000 to 3 March 2020. We then paused the project during the Covid-19 pandemic and re-ran the search on 1 July 2022. Two reviewers (BB and GI) independently assessed and screened all the titles and abstracts of the identified records to evaluate eligibility. The full text of all papers was retrieved and identified as potentially relevant by one or both review authors. Two reviewers then independently assessed these papers (BB and GI). Any disagreements on inclusion were resolved by discussion. No study was excluded on the grounds of methodological limitations.

The mapping exercise provided a snapshot view of the programmes available in May 2020, which was then updated in June 2022 as the UK came out of the Covid-19 pandemic. For the mapping exercise, one reviewer (SK) assessed the eligibility of each programme website or webpage, and a second reviewer (LP) checked the coded characteristics of 10% of the included programmes. Additional programmes were added through the peer review process.

Charting the data

A data extraction framework was developed for both the literature review and online mapping, which adapted the TIDieR intervention design framework (Hoffmann et al. 2014) (see Supplementary file 1). Descriptive information was extracted from each academic paper or exchange programme website (where relevant and available), including author; year; location; exchange objective; setting; participant job role; exchange organisation; exchange characteristics; and exchange duration. Information about how the academic paper was designed and conducted, along with findings, were also extracted for the scoping review.

For the mapping exercise, information about each programme was found from publicly available websites, webpages and linked documents. Some programmes had only a single webpage describing the exchange process and how to apply, whereas others had multiple web pages and linked documents that we used to map key characteristics.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Consistent with previous research on scoping reviews (Levac et al. 2010), we followed three steps in MS Excel separately for the scoping review and mapping exercise: analysing the data (descriptive summary and thematic analysis), reporting results, and applying meaning to results. We iteratively reviewed the study and programme characteristics and coded extracted descriptions to calculate basic frequencies in tables and charts (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al. 2010). This enabled a deeper analysis of the sample of texts and programme websites as separate data sets and consequently identification of where the significant gaps existed (Peters et al. 2015; Tricco et al. 2017). We then conducted deductive and inductive thematic analysis approaches using an analytic framework based on the data extraction guide.

As set out in the introduction, we aimed to describe the characteristics of WKEPs and their relationships to one another. During analysis, all authors brought together the identified characteristics from both data sources into a conceptual framework that is categorised based on WKEP opportunities. Each WKEP opportunity we identified was mapped into one or more of these categories. The categorisation was straightforward for many opportunities because they used a particular term, e.g., shadowing, placement, collaboration, or secondment. However, there were times we made interpretations based on descriptions as well as gaps in descriptions. For example, where no particular outputs were specified but it was clear that an immersive, in-person element was involved, possibly through reference to a ‘visit’, we assumed that some form of shadowing would be involved in the visit. See, for example, the Academy of Medical Sciences Daniel Turnberg Travel Fellowships as an example of this.

After an initial analysis, we re-examined data drawing on existing frameworks (Davies et al. 2015; Ward, 2017) and bringing in additional forms of knowledge exchange programmes we had previously overlooked (e.g., embedded researcher programmes). Our ambitions were to help the people running and participating in WKEPs navigate their way through the fragmented literature and programme opportunities, as well as highlight the key characteristics required when describing or advertising a new opportunity, or reporting the experience of having been on a WKEP. It should, however, be noted that the resulting framework is not an overarching ‘typology’ of exchanges. Throughout the scoping review and mapping exercise, we considered whether a typology might be possible. However, our ability to do so was limited, as we found it was not possible to assign a single label to some of the exchanges identified because they included more than one type of WKEP activity (e.g., job shadowing and project-based collaboration) and often other forms of knowledge exchange and/or learning. This was particularly true among exchanges that self-described as ‘fellowships’ or ‘sabbaticals’. Fellowships often included a range of activities or components that mapped onto shadowing, project-based collaboration and/or work placements, as well as other activities such as educational events, mentorship, action-learning sets and networking. Sabbaticals often overlap with secondments but could also take the form of other types of exchanges, as well as other ‘non-exchange’ activities. Thus, where included, fellowships and sabbaticals were mapped into their main activity type in the scoping review and by all the activities in the programme mapping.

Ethical approvals

The research was reviewed by the Observational and Interventions Research Ethics Committee at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. A favourable ethical opinion was confirmed on 11 March 2020 (Reference number 21668). All data included in this paper were obtained from within the public domain.

Results

Identification of texts and programmes

The process of identifying the included academic articles and programme webpages is detailed in a PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1). The initial scoping review search strategy identified a total of 6249 references. After the screening of the title and abstract, 1679 full-text articles were reviewed. From this, 147 full-text papers were included. The mapping exercise examined 970 search hits in Google (using various strategies described in Supplementary File 1), which identified 26 WKEPs. A further 22 WKEPs were identified through site-specific searches of research funding organisations (e.g., Academy of Medical Sciences) and a further 26 through word-of-mouth recommendations from interviewees from the wider scoping study and peer reviewers of initial manuscript drafts. A total of 74 WKEPs were analysed in the mapping exercise.

The characteristics of the texts included in the scoping review are available in Supplementary File 2, as well as on Rayyan.ai under the name ‘Workplace-based exchanges’. The detailed characteristics of the programmes included in the mapping exercise are in Table 1. Each of the programmes is described first by name, whether it was a regional, national or international programme, followed by the types of participants involved, such as Academic → Policy with the arrow indicating if it is uni- (→) or bi-directional (←→), and the duration. We categorise the WKEP activities undertaken during the programme into our proposed nomenclature of activities including job shadowing, project-based collaborations, work placement and secondments. We also capture other activities where they existed (e.g., networking, training) and financial support provided where available.

The scoping review included mostly self-reported case reports (142), followed by three primary research studies, two review articles, and no randomised trials. Thirty-three reports were described as evaluations. The results of the scoping review are presented grouped by the four main exchange activities we identified, including job shadowing, work placements, project-based collaborations and secondments.

While no quality assessments of the reporting of the scoping review articles or the programme webpages were carried out, the quality of reporting was generally poor, with no record covering all domains from our data extraction framework. To describe the characteristics of exchanges, we have grouped them into the ‘structures’, ‘processes’ and ‘outcomes’ of WKEPs. Where possible, we have used language and characteristics derived from an existing framework developed to produce a common route to describing knowledge mobilisation projects (Ward, 2017) and the wider knowledge exchange literature. The sections include:

-

-

Structures of WKEPs: aims, participants, geography, duration, and admission processes

-

-

Processes involved in WKEPs: activities, learning outcomes, and scheduling and approvals

-

-

Outcomes of WKEPs: benefits, outputs and outcomes, and theories of change

Structures of WKEPs

Aims of WKEPs

The aims of each text in the scoping review were grouped by the main exchange activity: job shadowing, work placements, project-based collaborations, and secondments. The aims of job shadowing exchanges were largely focused on facilitating personal and professional connections and brief insights into other settings. The aims of work placements were usually to supplement training, promote knowledge exchange and improve the quality of care. The aims of project-based collaborations were largely related to the completion of existing projects. The aims of secondment programmes were not always clear in the scoping review.

The most common aims we identified on the WKEP webpages were improving leadership and management skills (n = 25), developing networks or collaborations (n = 19), and improving understanding of another field or site (or country) to bring back knowledge to their employer (n = 19). See Supplementary File 3 for a full list. About half of the webpages suggested the WKEPs were multi-purposed. Most programmes aimed to serve the individual participant’s professional development (often through networks and skills development)—a micro-level aim—but many also aimed to improve organisational learning of the visitor’s and/or host’s organisation (interpreted as a meso-level aim), as well potentially the wider health and care system (a macro-level aim).

The direction of WKEP visits

In the scoping review, job shadowing and secondments were exclusively uni-directional, with no reciprocal visit reported. Similarly, most work placements were uni-directional exchanges, with a minority being bi-directional. Project collaborations were both uni- and bi-directional. Most WKEP webpages described a single participant visiting another workplace (i.e., uni-directional) without a reciprocal visit (51/74 programmes, 69%).

WKEP participants

The WKEPs we sought were intended for researchers, providers (including clinicians and non-clinicians), and policymakers working in health care. In the scoping review, all texts described programmes for healthcare providers or researchers. Three also included providers in social care. None involved policymakers. The type of participant varied by the programme’s main activity. For example, project-based collaborations typically target postgraduate early-career researchers. However, secondment participants were from any stage in their careers. Clinical work placements (that occurred outside usual postgraduate training programmes) were reported to be for trainees and qualified physicians, surgeons, general practitioners, accident and emergency doctors, psychiatrists, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, and allied health professionals. Most of these placements occurred towards the end of postgraduate training or within the first five years after gaining a specialist qualification. Non-clinical participants included managers, academics, social workers, and librarians. Some placements required a participant to be an MD or PhD candidate or to have completed a specialist diploma (e.g., a Diploma in Tropical Medicine for an exchange overseas).

In the mapping exercise, almost half of the programmes drew applications from providers (n = 27). Slightly fewer were aimed at people working in academia, including one for academic support staff (n = 23). Eight programmes were open to any of our three participant groups; however, two of these programmes were restricted to people working in digital health (ShadowMe, Shuri Network). Only two programmes were available to people working in social care (Bedford Council, International Social Worker Exchange Programme), and six programmes specifically targeted policymakers (e.g., CAPE, CSaP, Institute for Policy Research (University of Bath) Policy Fellowship (National), Royal Academy of Engineering (RAEng) Policy Fellowship programme (National), Royal Society Pairing Scheme, and UCL Visiting Policy Fellows programme). The programmes often specified an essential or desirable professional background for applicants. Where relevant to the WKEP, sub-speciality requirements were made evident for clinicians. The programmes for researchers often specified which disciplines were eligible for application, such as researchers in the physical sciences, social sciences, or humanities—none were available across disciplines.

Just over half of the programmes in the mapping exercise were available to people at any stage in their career (n = 33) and often specified that people should have finished their training or have post-doctoral standing. Thirteen of the exchanges were for people in an early career stage, nine for those in their mid to late career, and five for people in the later (or senior) stages of their career. We made assumptions that opportunities for PhD students (noting that these were not activities necessary to obtain their degree, which was an exclusion criterion) usually meant that the programme targeted applicants at early career stages.

The settings in which exchanges took place were also examined, identifying industry as an additional stakeholder group involved in WKEPs. Ward’s (2017) framework additionally identified members of the public acting as or on behalf of their communities and people in receipt of services, but we were unable to identify public involvement in any of the immersive WKEPs we identified in the literature or ongoing programmes.

Geography

In the scoping review, most reports focused on international travel (n = 92), and the minority were nationally focused (n = 9). The remaining reports were unclear as to whether the exchange involved international travel. In the mapping exercise, the converse was true. Around half of the programmes were described as nationally focused (n = 32), which meant that the activities and participants involved were carried out and recruited from the UK. Nine were regionally focused within the UK. Nineteen exchanges included international travel of UK-based participants.

Duration

In the scoping review, durations varied based on the type of programme. For example, job shadowing and clinical work placement-based programmes ranged from three days to two years, whereas secondments ranged from one through to three years. The duration of project-based collaborations was only reported in a minority of the texts (n = 34). In the remainder, it was either not clearly stated or lacking entirely. In the mapping exercise, the median programme duration was 12 months, with a range of one day to five years (see Table 1). Many programmes were either designed to be taken up part-time (e.g., Fellowships which had a range of activities, including WKEPs, planned to be undertaken over a year while maintaining full-time employment) or full-time during a shorter period of time (e.g., job shadowing placements), others had both full-time or part-time options.

Application and funding

We examined the descriptions of the application process and the funding available to participants. In the scoping review, whilst the exchange organising body, if there was one, was often acknowledged, the application and funding processes, if there were any, were seldom reported or poorly described. Much of the literature found described self-organised exchanges, where there was often no or limited involvement from an overarching organisation. In comparison, the mapping exercise provided more information, revealing that all the programmes which could be identified via a website usually required applications and many required interviews. Most programmes were designed to be run once per year. Almost all programmes described funding associated with the programme, including either a full or part-time salary, a stipend, research costs, and/or other benefits in kind, such as training and mentoring. The total amount available (for the programme and other components) was evident when the exchange was being provided as part of a research grant, but it was not possible to calculate when it covered participants’ salaries (and thus, the total cost depended on the applicants’ unique situations).

Processes of exchanges

Activities

As described earlier we identified four main types of activities involved in WKEPs.

Job shadowing

An arrangement whereby a visitor accompanies a host in their daily activities at work. Often a 1:1 arrangement that is driven by a desire for professional development or curiosity. It can also be used to provide an individual within a department the opportunity to work alongside more experienced colleagues so they can learn and develop within their current role. Shadowing can take the form of:

-

i.

Observation: a typical representation of what the host does daily. This can sometimes include an active involvement component such as the host briefing the visitor before an activity/meeting, then debriefing about lessons learnt).

-

ii.

Regular briefings: where the visitor shadows the host for specific activities during short periods of focused activity.

-

iii.

Hands-on: this is an extension of the observation model detailed above where the shadow starts to undertake some of the tasks they have observed (under the supervision of the host) (SOAS, n.d.; University of Bristol, n.d.; University of Cambridge, n.d.)

Shadowing is used in a variety of fields, and when applied as an experiential learning tool, it serves as a way for shadowers to understand close collaborators’ roles who are from different fields, providing first-hand insights about performance, roles, functions, practices, processes, logistics, etc. (Kusnoor and Stelljes, 2016; McDonald, 2005; Vega et al. 2021). Shadowing using observational practices has been used to increase student awareness of hospital pharmacy practice (Saine and Hicks, 1987), create opportunities for building relationships and trust (Aggarwal et al. 2022), broaden experience in different clinical settings and identify improvements to be incorporated into participants’ own clinical practice (Bridgwood et al. 2018, 2017). The nature of shadowing means it also helps overcome some of the safety issues and human resource governance issues related to a new person undertaking unsupervised ‘hands-on’ work in another setting, which is particularly relevant in healthcare settings.

Work placement

A period of work where participants experience working in a specific role with an organisation or within a variety of settings. Supervised work placements are common among work-experience and undergraduate students as well as among young adults in the form of apprenticeships as an alternative to higher education where they develop occupational competencies (Guile and Griffiths, 2001). Work placements are also seen as complementary to taught and practical courses in higher education (Bullock et al. 2009). In post-qualification setting, they tended to feature as part of a broader professional development programme, often as part of a ‘Fellowship’.

Project-based collaboration

These involve an ad-hoc arrangement by which a person is formally or informally brought into a project team for their external expertise. In either arrangement, participants’ contributions are often part-time, while they combine this with other work. Project-based collaborations can involve pairs or small groups of people brought together in pre-arranged meetings in each other’s workplaces to co-create solutions to pre-identified questions or problems or topics on which to collaborate beyond the meeting.

Secondment

A temporary transfer to another position or employment. In an internal secondment, the employee moves to a different part of the same organisation. In an external secondment, the employee temporarily works at a different organisation (O’Donoughue Jenkins and Anstey, 2017; Uneke et al. 2017). The embedded researcher model, where a researcher is based in a provider organisation, is often facilitated on a secondment basis. On expiry of the secondment term, the employee (the ‘secondee’) will typically ‘return’ to their original employer.

In the scoping review, we examined the main type of exchange activity reported, as the full range of activities was far less clear in the written reports in the academic literature than it was in the website-based mapping exercise, and we wanted to avoid making assumptions or omissions. Programmes that were typified by job shadowing (50/147, 34%) and secondments (50/147, 34%) formed the two largest categories in the scoping review. Some studies also referred to ‘project-focused’ programmes (25/147, 17%). There were also a relatively small number of ‘work placements’ (22/147, 15%).

For the mapping exercise, out of the 74 WKEP identified, 50 (68%) were composed of a single in-person WKEP activity, whereas 24 (32%) included two or more activities (see Table 1). There were a total 100 activities identified from the 74 WKEPs, of these 34 (34%) involved project-based collaborations, 24 (24%) involved work placements, 22 (22%) involved job shadowing and 20 (20%) involved secondments. A few programmes suggested that the activities carried out would depend on the interests and preferences of the visiting participant. Brief case studies of past participants were often provided to bring programmes to life and describe the types of activities that could be carried out. There were other common aspects of programmes, such as mentoring, networking or group-based learning, which are noted in Table 1, based on descriptions we assumed that these were not occurring within each other’s workplaces.

Learning expectations

In this part of the analysis, we were particularly interested in how learning was captured during the WKEP. One route to learning through direct immersive experiences like shadowing, work placements, secondments, and project-based collaborations involves reflecting on the experience through writing or discussion afterwards to develop or consolidate new skills, new attitudes, or new ways of thinking. This is referred to as experiential learning in the education literature (Lewis and Williams 1994, p. 5).

The scoping review revealed a range of important insights about the learning process. For example, job shadowing exchanges often had a requirement to set learning objectives in advance, which were then reviewed after the exchange. There were pre- and post-virtual meetings reported, along with an end-of-exchange face-to-face meeting intermittently reported. Whereas a small number of work placements required learning objectives to be set in advance, less than one in four reported reviewing these after the exchange. Project-based collaborations requiring learning objectives were generally not described, although project deliverables were stated. It was unclear whether secondment participants set learning objectives in advance or indeed reflected on their experiences beyond what was captured in the published literature. Regarding work placements, additional training was commonly offered to support the placement, such as language training if it was an international exchange. The mapping exercise revealed very little about learning expectations and the learning process.

Scheduling and permissions

The scoping review revealed that most job shadowing exchanges were informally organised between individuals and did not follow a prescribed framework. Instead, those undertaking an exchange were able to dictate the exchange format and timetable. The permissions for job shadowing were required from the participant’s post-graduate training programme and/or employer, as it was not a core part of training and/or needed permissions from the hosting organisation (e.g., GP surgery). There were no specific occupational health checks described. Visa requirements were in line with the law in the respective countries for international exchanges. Exchanges could take place at any suitable time. Time taken out of training was either taken as annual or study leave or added onto the length of a degree/training or integrated into the course length. Fourteen reports explicitly identified themselves as approved Out of Programme Experiences (OOPEs)—whereby postgraduate trainee doctors are granted a set period of time out of their speciality training rotation. There were usually two organisations linked in the exchange and, at times, three (e.g., Erasmus organising committee, host organisation, and the organisation of the exchange participant). However, their exact involvement was not always clear.

For work placements reported in the scoping review, the pairing was either self-organised, arranged through a network, or arranged by an overarching organisation. Permission to undertake a clinical placement was often needed from the employer, training deanery, or medical/nursing council. Occupational health checks for clinicians and security requirements were again largely not described. Typically, there was only one overarching organisation however, up to ten were reported. Project-based collaborations involved matching the participant and host based on the needs of the project. It was largely unclear how time was accounted for, and what permissions and human resources checks were required. There was often a lead university coordinating the exchange with administrators. Regarding secondments, there was often a single lead organisation which led the secondments. It was often unclear how the exchange was arranged, yet some were described as self-organised, and a smaller proportion were available through facilitated schemes. Information about prior permissions, HR checks and training was again generally not reported.

The mapping exercise revealed no information around the ‘back end’ of the exchange process beyond the steps of applying.

Outcomes

Benefits, outputs and outcomes

Across both the mapping exercise and the scoping review, the benefits, outputs, and outcomes of exchanges were implicitly laden in the aims and descriptions of the programmes. The scoping review found that exchange benefits and outcomes were broadly themed into personal, professional, and organisational categories. Regarding job shadowing, personal outcomes included broadening horizons, increasing motivation to learn, developing cultural awareness and open-mindedness, enhancing self-confidence, gaining knowledge in new subject areas, including teaching methods and improving language skills. Work placements were described as leading to opportunities to gain experience in new clinical settings (e.g., emergency situations), practice evidence-based medicine, training in ethics, avoiding isolation and leadership training. There were no explicit benefits associated with project-based collaborations. The benefits of the secondments described in the scoping review included opportunities to be away from day-to-day workplace obligations, develop career-enhancement skills, undertake strategic secondments to make up shortfalls in specialist skills; to transition between roles; support recruitment and retention, and provide conflict resolution support.

In the mapping exercise, we found that fewer than half of the programmes described benefits for the main participants. The benefits were sometimes supported by testimonials from past participants describing a positive experience, but it was unclear exactly how benefits or outcomes would be achieved and when. The most common benefits identified included:

-

1.

Building partnerships / collaborations (or 1:1 relationships)

-

2.

Preparing participants for employment (through skill development)

-

3.

Increasing the professional reputation of participants

-

4.

Supporting international development in another country

-

5.

Improving the well-being of local communities

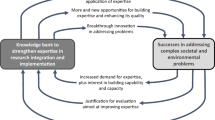

Theories of change and evaluations

As might be expected based on the variation in reporting and advertising of the benefits and outcomes described above, there were very few examples of theories of change described. While the scoping review found no examples of this, the mapping review identified a few. Only one programme, CSaP, offered an explicit theory of change. The CSaP exchange programme was offered to early, mid and senior career-level policymakers. At all levels, the programme relied on the logic that: ‘if’ researchers and policymakers build professional relationships, ‘then’ more research will be transferred into policy. A small number of other programmes provided sufficient information that a probable theory of change could be developed. This was particularly true when programmes were narrow in scope or described a clear problem they were trying to solve. For example, the 70@70 programme made clear that the problem the programme sought to solve was a lack of nursing input into research at a national level. The aim of the 70@70 Programme could thus be summarised as: ‘if’ more nurses are funded to provide input to the NIHR programme across the country, ‘then’ nursing research priorities will be better represented at the system level.

Evaluations

Of the 147 academic papers included in the scoping review, 33 self-described as evaluations (and these are tagged in Supplementary File 3). The mapping exercise identified only five evaluations of programmes (CSaP, HEE Deaneries Global Health Fellowship, HEE Improving Global Health Fellowship, NIHR70@70, and Paired Learning). It is likely that other programmes have conducted evaluations or pilot studies, but have not made reports publicly available or were not picked up in the searches. This assumption is driven by key informant conversations we had with exchange programme leaders as part of the background work for this scoping study. Had more evaluations been available, the theories of change may have been more apparent.

Discussion

Principal findings

This scoping study has mapped the systems, processes, and outcomes of a form of knowledge exchange in the field of health and care that we labelled ‘Workplace-based Knowledge Exchange Programmes’ (WKEPs). WKEPs provide opportunities for people from different disciplines or locations to spend a temporary amount of in-person time in another workplace, learning from observing a different work environment and learning from those with differing expertise or offering their expertise.

The WKEPs included in our scoping study were mostly uni-directional but otherwise varied. They ranged in duration from a single day to five years. The aims and benefits of these exchanges in the health and care field were found to exist at the individual/micro (e.g., developing networks), organisational/meso (e.g., improving understandings of another sector or site - including outside the UK - to bring back to participants’ own workplace), and system/macro levels (e.g., producing research evidence). The entry process into WKEPs ranged from informal case-by-base arrangements for job shadowing to applications and interviews for other WKEP-related activities such as project-based collaborations, work placement, or secondments. This was particularly the case when WKEP formed part of a wider range of professional development and knowledge exchange activities, often under the generic term of ‘Fellowship’. The consolidation of knowledge through reflection often depended on the formality of the exchange. Some WKEPs involved reviewing pre-set objectives at the end of the programme, logging continuing professional development points, or formal assessments by the hosting organisation.

We found that the programmes in the mapping exercise and scoping review could be described as involving one or more of the following activities: ‘job shadowing’, ‘work placements’, ‘project-based collaborations’, and/or ‘secondments’. These terms were derived from the description of activities in the WKEPs’ webpages and the case reports in the scoping review, as well as from the knowledge exchange and mobilisation and education literature. To clarify what is meant by each knowledge exchange activity and their relationships to each other, we have developed an applied conceptual framework which builds on existing frameworks (Davies et al. 2015; Ward, 2017). This distinguishes between WKEP activities and aims to help people or organisations facilitating, participating in, or researching knowledge exchanges describe their knowledge exchange opportunity (see Table 2).

Reflections on challenges and implications for WKEP organisers and researchers

We experienced three main difficulties in seeking to understand the characteristics of WKEPs in the health and care field in the UK. This incited reflection on the challenges potential WKEP participants may face when seeking out exchanges. These challenges included: (i) difficulty identifying WKEPs, (ii) WKEPs being poorly reported and advertised, and (iii) imbalances in WKEP opportunities. Based on these we recommend mechanisms through which to improve access and awareness of WKEPs drawing on the finding of this study.

Firstly, it was very difficult to identify WKEPs online. Using the scoping review’s search terms (and simplified search terms) in Google revealed only five relevant programmes, whereas site-specific searches of research funding bodies such as the Medical Research Council or Academy of Medical Sciences revealed a further 22, and word-of-mouth approaches from well-networked interviewees (findings from interviewees are presented elsewhere - see Kumpunen et al (2023)) and peer reviewers revealed an additional 26. Enacting the well-thought-through searching strategy proved so challenging that we concluded that unless potential WKEP participants were well-connected or aware of websites from which to launch searches, the process of identifying programmes would likely prove challenging. This could be due to a lack of shared terminology to describe the particular immersive form of knowledge exchange we were interested in. The consequences of not having terminology, as highlighted by Farley-Ripple et al. (2020), include interested stakeholders overlooking existing research on this topic, leading to “wasted research, repetitive investigations leading to the same conclusion, and, unfortunately, an over-claiming about what new research in this area can deliver” (p. 8). To address this, descriptions in online advertisements and publications could be linked to the conceptual framework’s vocabulary, thus creating semantic ties and building a more easily searchable space. Furthermore, to bring together all WKEP-related documents, such as advertisements, programme testimonials, and evaluations, there may be value in developing (and widely publicising) an open-access database or repository on all WKEPs and possibly other knowledge exchange opportunities. This could be established and (co-)hosted by leading national organisations that champion a culture which values and incentivises the production and the use of knowledge and that have long-term funding to support the required necessary updates. For England, these could include UK Research & Innovation, Research England, NHS England, Health Education England (now also part of NHS England), the Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management and/or Higher Education Institutions, such as universities with expertise in the field of knowledge exchange in health and care.

Secondly, the WKEPs we identified were poorly reported and advertised. We were unable to fully complete the data extraction form (available in Supplementary File 1) for any single paper or programme website. Regarding reporting gaps, the mapping exercise provided information about the aims, duration, application process and funding, but could not cover the areas the scoping review texts provided, such as the learning objectives and approvals and permissions. Knowledge gaps that were not consistently covered included which outcomes are achievable and when, the logic of the programme (echoing Oliver and colleagues’ (2022) experience), as well as the costs of programmes. The specific methods for actually exchanging knowledge were also poorly articulated, as was first identified by Ward (2017). Further, evaluations of WKEPs were also notably absent from the literature and web pages we examined. This was unsurprising, as formal evaluations have proved highly challenging and relatively rare in the knowledge mobilisation space (Davies et al. 2015). The challenges of mapping and the inability to gain a comprehensive understanding of any single knowledge exchange programme has been identified as a problem in other similar reviews and mapping projects (c.f., (Bridgwood et al. 2018; Oliver et al. 2022; Ward, 2017)). Therefore without addressing poor reporting, it will be difficult for the field to continue building upon the existing frameworks (c.f. (Best and Holmes, 2010; Davies et al. 2015; Langer et al. 2016; Ward, 2017; Ward et al. 2012).

To support the improved reporting and advertisement of any existing or future WKEPs, we have produced good practice principles adapted from the TIDieR intervention design framework (Hoffmann et al. 2014), the applied conceptual framework we produced, and existing frameworks (Ward, 2017) (see Table 3). The reporting principles are valuable in two respects. They can help exchange organisers reflect on key aspects of their WKEPs, including their aims, theory of change, benefits, and costs. They also offer a mechanism for enabling programme organisers to communicate these details more clearly to applicants and their employers—making business cases easier to defend. The reporting principles also provide a structure to exchange participants around which to describe their experiences in case reports, should they publish them. The advertising and reporting of future WKEPs could be improved through more comprehensive descriptions of the induction, exchange and post-exchange activities, experiences and outcomes achieved. We would value organisations and individuals applying the principles and feeding back their comments to the authors of this study.

Finally, the conceptual framework was challenging to develop because of imbalances in opportunities. There were very few WKEP opportunities within social care, a disappointing but perhaps unsurprising finding considering the sector has long suffered from underinvestment in its services and human capital. Further, we examined opportunities for three stakeholder groups of interest in this study—providers, policymakers, and academics—but the bulk of texts in the scoping review and around half of the programmes in the mapping exercise were aimed at providers (in the health sector). Only six programmes targeted policymakers as the primary (visiting) participants (e.g., CAPE, CSaP, Institute for Policy Research (University of Bath) Policy Fellowship (National), Royal Academy of Engineering (RAEng) Policy Fellowship programme (National), Royal Society Pairing Scheme, and UCL Visiting Policy Fellows programme). One possible explanation for the gaps in opportunities for policymakers is that other types of knowledge exchange and professional development opportunities are more common than WKEPs, such as mentoring or undertaking a short course or Masters-level degree. However, we were unable to identify literature to confirm this. That said, a study on professional development strategies for the education of policymakers suggested typical routes to professional development included staff exchanges and study visits, postgraduate programmes, and internships, as these were identified to enhance the knowledge and skills of policy-makers, particularly for those who have been transferred to work in new areas (Nguyen, 2019). Thus, other possible explanations for the difference between opportunities for health care providers versus policymakers are that there are more NHS staff than policymakers or that it is not within the professional culture among policymakers (or possibly even appropriate) to publicly advertise or publish about professional development opportunities internal to the subsector. The nature of the day-to-day activities involved in each role, which may, for example, be more desk-based for policymakers compared to providers, may lend themselves less well to short in-person WKEPs. There is a need to further explore knowledge exchange opportunities for policymakers and social care practitioners.

To aid programme organisers aiming to address the imbalance in opportunities, there would be benefits in organisers building on existing research and tools. For example, the barriers to participation have been highlighted as upfront travel costs, administrative burdens associated with drafting exchange agreements, or loss of participant income (Kumpunen et al., 2023). To overcome these barriers, organisers could instead consider using virtual exchanges, which can minimise travel costs (relative to in-person WKEPs) and have been found to instil empowerment within participants, promote independent and collaborative learning skills, and inspire local health system development among health professionals (Bridgwood et al. 2023). Where preferences are for in-person immersive WKEPs (and administrative burden is preventing participation), organisers could borrow from the existing tools, such as the Paired Learning programme’s publicly-available toolkit, which provide clear guidance and document templates (e.g., human resources approval letters) on how to replicate or adapt their model.Footnote 6 Successful adaptations of the original Paired Learning Programme involving multi-disciplinary team members engaging in a more condensed approach have been described in the literature (Houston and Morgan, 2018). A similar toolkit is available for general practitioner and hospital-based consultant exchanges.Footnote 7 Moreover, a set of guiding questions has also been produced to help organisations design an embedded researcher initiative.Footnote 8 Where a particular approach has been chosen, borrowing from existing knowledge about the barriers and facilitators may be of value. For example, when developing a secondment programme into policymaking environments, organisers could think about the extent they can build identified facilitators into their programme design, such as establishing a prior relationship between the two organisations and building a civil servant culture that values the use of research in policymaking (O’Donoughue Jenkins and Anstey, 2017). Likewise, other studies looking at secondments have identified the importance of participants buddying up, strong team leadership, strong brokers’ interpersonal skills, and two-year part-time contracts (Wye et al. 2020). Careful planning and adaptation of the existing evidence and tools could help address the imbalance of WKEP opportunities.

Strengths and limitations

Relatively little was known about the characteristics of WKEPs in health and care in the UK before this scoping study. Our searches were systematic, and the mapping of characteristics was comprehensive. Overall, we found 147 texts and 74 programme webpages and brought together data wherever available to strengthen our understanding of WKEPs and develop a framework of activities. Nevertheless, the methods of data collection in the scoping study were limited by time and budget, as well as methodological limitations. Additionally, our research team was dominated by five general practice providers (three of whom were in academic roles) and a health policy researcher (who was previously a policymaker)—thus, we lacked the perspectives of current policymakers and people in social care. As is common with scoping projects, we attempted to make our search strategies as sensitive as possible. But we know the exchanges we identified in the review and mapping exercise are likely to represent only a small proportion of the total number of exchanges that take place and that these will change over time. Indeed, it is likely that those reported and identified here are skewed towards the more structured programmes that tend to encourage report writing, publication, and advertising on public platforms. The mapping exercise, by its nature, excluded self-organised exchanges and those without an online description. Due to time and budget restrictions, we were unable to co-develop or test our ‘next steps’ recommendations with stakeholders, but this represents an opportunity for further research. Finally, we also recognise that the health and care sector also encompasses roles which may not clearly fit into the categories of providers, policymakers or researchers, for example, digital health developers in the private sector, management consultants or the pharmaceutical industry—as is suggested, the proposed conceptual framework and reporting principles should be amended as more information becomes available about WKEPs and their participants.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified the characteristics of ‘Workplace-based Knowledge Exchange Programmes’ (WKEPs) by systematically examining 147 relevant texts and 74 programme websites. There was significant variation in the length, setting, and formality of WKEPs. The terms used to describe them were often applied interchangeably and covered a range of activities, particularly terms like ‘fellowship’, but we found that four activities were common to WKEPs: job shadowing, work placements, project-based collaborations, and secondments. The true extent of WKEPs is unknown, as their reporting in academic literature appears to be highly heterogeneous and opportunities relatively elusive in online searches. Two groups of participants appeared to be underrepresented in our sample, people working in social care and policymakers (working on health or social care). Moving forward, we recommend using common and consistent language by using the four terms above to describe knowledge exchange activities which involve a period of time spent immersed in person in another workplace (see Table 2). Secondly, we suggest an online register of opportunities be established. Thirdly, we encourage employers of providers, academics, and policymakers to develop WKEPs as a form of professional development for their staff, drawing from the existing programme examples identified here, as well as using the principles for advertising and reporting experiences provided (see Table 3). Despite this scoping review providing new insights about WKEPs, there is an ongoing need to better capture their benefits, outcomes, and costs related with WKEPs in order to improve their application in the field of knowledge mobilisation.

Data availability

In the scoping review, we analysed journal articles, many of which are accessible publicly, but some of which are only available behind journal paywalls. Our analysis of the included articles scoping is available in Supplementary file 2, as well as on Rayyan.ai under the label ‘Workplace-based exchanges’. The mapping exercise examined publicly available websites, and our analysis of these are summarised in an MS Excel table which is available by request from the authors.

Notes

References

Aggarwal P, Fraser A, Ross S, Scallan S (2022) Learning from the GP-consultant exchange scheme: a qualitative evaluation. MedEdPublish 12:51. https://doi.org/10.12688/mep.17542.1

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Best A, Holmes B (2010) Systems thinking, knowledge and action: towards better models and methods. Evid Policy 6:145–159. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410X502284

Bridgwood B, Park J, Hawcroft C, Kay N, Tang E (2018) International exchanges in primary care—learning from thy neighbour. Family Pract 35:247–252. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmx101

Bridgwood B, Willoughby H, Attridge M, Tang E (2017) The value of European exchange programs for early career family doctors. Educ Prim Care 28:232–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2017.1315618

Bridgwood B, Woolley K, Poppleton A (2023) A scoping review of international virtual knowledge exchanges for healthcare professionals. Educ Prim Care 34:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2022.2147025

Bullock K, Gould V, Hejmadi M, Lock G (2009) Work placement experience: should I stay or should I go? High Educ Res Dev 28:481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903146833

Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, Kastner M, Moher D (2014) Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 67:1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

Davies HT, Powell AE, Nutley SM (2015) Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care: learning from other countries and other sectors - a multimethod mapping study. Health Serv Deliv Res 3:1–190. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr03270

Farley-Ripple EN, Oliver K, Boaz A (2020) Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00571-2

Guile D, Griffiths T (2001) Learning through work experience. J Educ Work 14:113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028738

Harvey G, Kitson A (2016) PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci 11:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman DG, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br Med J 348. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687

Houston JFB, Morgan JE (2018) Paired learning—improving collaboration between clinicians and managers. J Health Organ Manag 32:101–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-10-2017-0263

Klaber RE, Smith L, Lee J, Abraham R, Lemer C (2011). Paired Learning—clinicians and managers learning and working together. Br Med J 343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5672

Kumpunen S, Matthews J, Amuthalingam T, Irving G, Bridgwood B, Pettigrew LM (2023). Workplace-based knowledge exchange programmes between academics, policymakers and providers of health care: a qualitative study. BMJ Leader 0:1-5. https://bmjleader.bmj.com/content/leader/early/2023/07/10/leader-2023-000756.full.pdf

Kusnoor AV, Stelljes LA (2016) Interprofessional learning through shadowing: insights and lessons learned. Med Teacher 38:1278–1284. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2016.1230186

Langer L, Tripney JS, Gough D (2016) The science of using science: researching the use of research evidence in decision-making (Report No. 3504), (EPPI-Centre reports 3504). EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, London, UK, https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3504

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Lewis LH, Williams CJ (1994) Experiential learning: past and present. New Dir Adult continuing education 1994:5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.36719946203

Lynch EA, Mudge A, Knowles S, Kitson AL, Hunter SC, Harvey G (2018) “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”: a pragmatic guide for selecting theoretical approaches for implementation projects. BMC Health Serv Res 18:857. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3671-z

Marshall M, Pagel C, French C, Utley M, Allwood D, Fulop N, Pope C, Banks V, Goldmann A (2014) Moving improvement research closer to practice: the Researcher-in-Residence model. BMJ Qual Saf 23:801–805. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002779

McDonald S (2005) Studying actions in context: a qualitative shadowing method for organizational research. Qual Res 5:455–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794105056923

Nasir L, Robert G, Fischer M, Norman I, Murrells T, Schofield P (2013) Facilitating knowledge exchange between health-care sectors, organisations and professions: a longitudinal mixed-methods study of boundary-spanning processes and their impact on health-care quality. Health Services and Delivery Research. NIHR Journals Library, Southampton (UK), 10.3310/hsdr01070

Nguyen HC (2019) An investigation of professional development among educational policy-makers, institutional leaders and teachers. Manag Educ 33:32–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020618781678

NIHRtv, 2022. An introduction into knowledge mobilisation for researchers. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l1R0sdSark (Accessed 28 June 2023)

Nilsen P (2015) Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 10:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

O’Donoughue Jenkins L, Anstey K(2017) The use of secondments as a tool to increase knowledge translation Public Health Res Pract 27(1):e2711708. https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp2711708

Oliver K, Hopkins A, Boaz A, Guillot-Wright S, Cairney P (2022) What works to promote research-policy engagement? Evidence & Policy 1:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16420918447616

Oliver K, Kothari A, Mays N (2019) The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research. Health Research Policy Syst 17:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3

Oliver K, Lorenc T, Innvær S (2014) New directions in evidence-based policy research: a critical analysis of the literature. Health Res Policy Syst 12:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-12-34

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Khalil H, Larsen P, Marnie C, Pollock D, Tricco AC, Munn Z (2022) Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid Synth 20:953–968. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-21-00242

Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB (2015) Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 13:141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Rycroft-Malone J, Burton C, Wilkinson J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Baker R, Dopson S, Graham I, Staniszewska S, Thompson C, Ariss S, Melville-Richards L, Williams L (2015) Collective action for knowledge mobilisation: a realist evaluation of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. Health Services and Delivery Research. NIHR Journals Library, Southampton (UK), https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr03440

Saine DR, Hicks CI (1987) Shadowing program to increase student awareness of hospital pharmacy practice. Am J Hosp Pharm 44:1614–1617. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/44.7.1614

SOAS, nd. SOAS Work Shadowing Scheme. Available at: https://studylib.net/doc/8033891/work-based-shadowing (Accessed: 28 June 2023)

Tricco AC, Langlois E, Straus SE, World Health Organization (2017). Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258698 (Accessed 28 June 2023)

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169:467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Uneke CJ, Ezeoha AE, Uro-Chukwu HC, Ezeonu CT, Igboji J (2017) Promoting researchers and policy-makers collaboration in evidence-informed policy-making in nigeria: outcome of a two-way secondment model between University and Health Ministry. Int J Health Policy Manag 7:522–531. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.123

University of Bristol, n.d. Job shadowing guidelines. Available at: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/staffdevelopment/professional-services/job-shadowing/ (Accessed 28 June 2023)

University of Cambridge, n.d. Personal and Professional Development: Types of job shadowing. Available at: https://www.ppd.admin.cam.ac.uk/professional-development/job-shadowing/types-job-shadowing (Accessed 28 June 2023)

Vega RM, Peláez E, Raj B (2021) Shadowing as peer experiential learning for faculty instructional development strategy: A case study on a computer science course. Int J Educ Res Open 2:100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100091

Ward V (2017) Why, whose, what and how? A framework for knowledge mobilisers. Evid Policy 13:477–497. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426416X14634763278725

Ward V, Smith S, House A, Hamer S (2012) Exploring knowledge exchange: a useful framework for practice and policy. Soc Sci Med 74:297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.021

Ward V, Tooman T, Reid B, Davies H, Brien BO, Mear L, Marshall M (2021) A framework to support the design and cultivation of embedded research initiatives. Evid Policy 17:755–769. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426421X16165177707227

Wye L, Cramer H, Beckett K, Farr M, le May A, Carey J, Robinson R, Anthwal R, Rooney J, Baxter H (2020) Collective knowledge brokering: the model and impact of an embedded team. Evid Policy 16:429–452. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426419X15468577044957

Acknowledgements

UK Research and Innovation Research England funded the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to identify knowledge exchange activities that facilitate the use of existing research, activities aimed at improving the dialogue between universities and policymakers, as well as examining the implications for policy and practice as to how to improve access to such opportunities (LSHTM-QR-SPF-2019/20). We are grateful to Coral Pepper, Clinical Librarian, at University Hospitals Leicester, for assistance with the scoping review. We are also grateful to our peer reviewers— Kirsten Armit, Annette Boaz, Jeremy Brown, and Ana Luisa Neves—for their comments on earlier drafts from which this article was developed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design- All; data collection- SK, BB, GI and LP; analysis and interpretation of results- All; draft paper preparation- All. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The research was reviewed by the Observational and Interventions Research Ethics Committee at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. A favourable ethical opinion was confirmed on 11 March 2020 (Reference number 21668). The data presented here does not include data from human participants. All data included in this paper were obtained from within the public domain.

Informed consent

No human subjects were involved, and all data was publicly available. Informed consent was not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumpunen, S., Bridgwood, B., Irving, G. et al. Workplace-based knowledge exchange programmes between academics, policymakers and providers in the health and social care sector: a scoping review and mapping exercise. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 507 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01932-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01932-3

This article is cited by

-

Social Processes of Public Sector Collaborations in Kenya: Unpacking Challenges of Realising Joint Actions in Public Administration

Journal of the Knowledge Economy (2024)