Abstract

Acoustic signals that reliably indicate body size, which usually determines competitive ability, are of particular interest for understanding how animals assess rivals and choose mates. Whereas body size tends to be negatively associated with formant dispersion in animal vocalizations, non-vocal signals have received little attention. Among the most emblematic sounds in the animal kingdom is the chest beat of gorillas, a non-vocal signal that is thought to be important in intra and inter-sexual competition, yet it is unclear whether it reliably indicates body size. We examined the relationship among body size (back breadth), peak frequency, and three temporal characteristics of the chest beat: duration, number of beats and beat rate from sound recordings of wild adult male mountain gorillas. Using linear mixed models, we found that larger males had significantly lower peak frequencies than smaller ones, but we found no consistent relationship between body size and the temporal characteristics measured. Taken together with earlier findings of positive correlations among male body size, dominance rank and reproductive success, we conclude that the gorilla chest beat is an honest signal of competitive ability. These results emphasize the potential of non-vocal signals to convey important information in mammal communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the many functions of animal communication is to mediate social interactions related to intrasexual competition and intersexual mate choice1,2,3. In particular, acoustic signals have been found to play a crucial role in facilitating assessment of rivals and in the choice of mates1,2,3,4. Acoustic signals can convey information about the sender’s competitive ability, body size and/or condition5,6,7. Signals are deemed honest when they provide reliable information about the sender4. Signals remain honest because they are directly linked to the sender’s physical characteristics, such as body size or condition that cannot be easily faked (called indexical signals), the costs of producing them are prohibitively high for low quality individuals (handicaps), or individuals who produce dishonest signals are punished and suffer reduced fitness3,4,8,9.

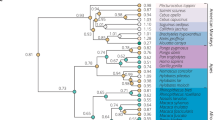

The relationship between body size and acoustic properties of signals are of particular interest in species in which body size determines fighting ability and reproductive success. Due to the allometric relationship between vocal tract length and body size, a strong association between the acoustic structure of vocalizations and body size has been observed4,7. For example, negative correlations between body size and formant dispersion (average spacing between resonant frequencies), indicating that (within-species) these are honest signals, have been found in a growing number of species such as rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta)10, black and white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza)11, red deer (Cervus elaphus)5, fallow deer (Dama dama)12, koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus)13, giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca)14, North American bison (Bison bison)15, southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonine)16, American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis)17 and corncrakes (Crex crex)18.

In contrast to vocal communication, the relationship between body size and non-vocal acoustic signals has received far less attention19,20,21. Non-vocal signals are also thought to be important in intrasexual competition and intersexual mate choice and thus under similar sexual selection pressure1. A study testing for the relationship between body size and acoustic structure of non-vocal signaling in mammals found that the peak frequency of knee clicking in eland (Tragelaphus oryx) reliably indicates body size21.

Another non-vocal signal is the chest beat which is the climax of the gorilla chest beating display22. Chest beating is performed when individuals usually rise bipedally and rapidly beat their chests with cupped hands in rapid succession, producing an impressive drumming sound (Fig. 1). The chest beat is sometimes preceded by a hooting vocalization and accompanied by slurred growling but not always22,23,24. The chest beat has both acoustic and visual components, and therefore is an example of a multimodal non-vocal signal. This multimodal long-distance signal, which can be heard over 1 km away, is most commonly performed by adult males (silverbacks)22. Gorillas are highly sexually dimorphic, living in predominantly one-male, multi-female social groups, resulting in high male–male competition25,26. Females may disperse among social groups, thereby exhibiting female choice for mates27. Previous research has suggested that the chest beat is an important signal in male–male competition and mate choice22. Silverbacks chest beat relatively infrequently, on average 0.5 times per 10 hours23, but may chest beat for as much as once every few minutes during intergroup encounters (M. Robbins personal observation). Silverbacks also chest beat more frequently on days when females are in estrous28. Body size of males is thought to reflect fighting ability as it strongly correlates with dominance rank in multi-male mountain gorilla groups and reproductive success in both species of gorillas29,30,31. However, it remains unclear what information chest beats convey and whether they reliably indicate the body size of the sender.

We examined whether the gorilla chest beat is an honest signal of body size. As a measure of body size we used back breadth, which is likely to be a good proxy for chest volume and therefore a relevant trait to correlate with acoustic properties of chest beats. First, we examined the relationship between body size and the peak frequency of the chest beats (the non-vocal drumming sound). We tested the prediction that larger males have significantly lower peak frequencies than smaller males, because there should be a direct relationship between the size of the animal producing the sound and low dominant frequency32,33. Second, we correlated body size to several temporal characteristics of chest beats, such as duration, number of beats and beat rate (number of beats per second). We tested the prediction that larger males chest beat for a longer duration, with a greater number of beats at a faster beat rate than smaller males. Because acoustic signaling is thought to be energetically costly to produce, larger males may be better equipped to produce them34,35,36,37.

Results

Frequency of chest beats

During 3211 h of focal animal sampling (mean per male = 128; range 8–307; N males = 25), we observed 503 chest beats, which is an average of 1.6 chest beats every ten observation hours (SD: 1.4; Table 1).

Peak frequency

The mean peak frequency per male was 638.9 Hz (range: 459.0–1003.0 Hz; SD: 88.8; N data points = 36; N males = 6; Table 2). The mean within- and between-individual coefficients of variation (CV) for peak frequency were 13.3% and 15.5%, respectively. The chest beat of larger males comprised significantly lower peak frequencies than smaller males (Table 3; Fig. 2). An increase in one standard deviation in body size resulted in a decrease of 34.6 Hz in median peak frequency.

Chest beat duration

The mean chest beat duration per male was 0.65 s (range 0.17–2.82 s; SD: 0.29; N data points = 36; N males = 6; Table 2). The mean within- and between-individual CV for chest beat duration were 39.0% and 85.6%, respectively. Chest beat duration was not significantly associated with body size (full null model comparison χ21 = 0.707; P = 0.401).

Number of beats

The mean number of beats per chest beat and male was 8 (range 3–27; SD: 2.8; N data points = 36; N males = 6; Table 2). The mean within- and between-individual CV for the number of beats per chest beat were 31.6% and 67.9%, respectively. The number of beats per chest beat was not significantly associated with body size (full null model comparison χ21 = 0.446; P = 0.504).

Beat rate

The mean beat rate per chest beat and male was 13.7 beats/s (range 9.165–18.114; SD: 1.84; N data points = 36; N males = 6; Table 2). The mean within- and between-individual CV for beat rate were 13.5% and 10.1%, respectively. The beat rate was not significantly associated with body size (full null model comparison χ21 = 0.125; P = 0.724).

In addition to back breadth we also repeated the above analyses using crest-back score, which is a composite measure combining back breadth and sagittal crest height31. The two body size measures are highly correlated31 so we did not fit a model that included both variables. The results of the models with only crest-back score were similar to the ones with back breadth, with crest-back score being significantly correlated with peak frequency, but not with any of the temporal measures (Supplementary Note and Table S1).

Discussion

Our results indicate that mountain gorilla chest beats reliably convey information about the body size of the sender. Larger males consistently emitted chest beats with lower median peak frequencies than smaller males. This finding is an important contribution to the growing literature on honest signaling of body size in acoustic communication, which has predominantly focused on vocalizations5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. This is one of a few studies in mammals demonstrating that body size is reliably encoded in a non-vocal acoustic signal. In eland bulls, body size (skeletal measures and muscle mass) was shown to be negatively correlated with the peak frequency of knee clicks21. In adult male gorillas, body size (a composite measure combining crest height and back breadth) is thought to reflect competitive ability because it correlates with dominance rank in multi-male groups and reproductive success31. Additionally, silverbacks chest beat more frequently on days when females are in estrous, presumably as a courtship display28. Taken together, this strongly suggests that the chest beat is an extremely important signal in intrasexual competition and intersexual mate choice in gorillas. Moreover, given that different forms of drumming behaviour, incorporating substrates other than the chest or body, are surprisingly common in a wide range of animals19,20, it is likely that this understudied non-vocal acoustic mode of communication functions to reliably indicate competitive ability in many other species as well.

Our measure of body size, back breadth, likely correlates with a range of morphological traits, including chest volume, pulmonary capacity and hand size. Therefore it is unclear which specific trait or traits are responsible for driving the inverse relationship between back breadth and peak frequency. Moreover, gorillas like other non-human primates possess laryngeal air sacs which are thought to act as resonators, enhancing acoustic signals4,11,24. Indeed, gorillas appear to use laryngeal air sacs during growling vocalizations which often accompany chest beating24. The volume of laryngeal air sacs is likely to be directly correlated with body size, at least within-species (which in orangutans (Pongo) can reach a massive 6 L38). Thus larger males are expected to have larger laryngeal air sacs than smaller males, further lowering the resonating non-vocal frequencies produced whilst chest beating. However, our knowledge of the size and function of laryngeal air sacs in primates and other taxa remains poor39.

Both dominant and subordinate male gorillas emitted chest beats. In general, gorilla males likely chest beat to attract estrous females and intimidate rivals22,28,31. However, younger subordinate males may also chest beat as a means to fine tune this signal and acquire social feedback from conspecifics. The importance of practice is evident as infants as young as one year of age commonly start emitting chest beats during social play22,40. Interestingly, the chest beat rate (number of chest beats per unit time) in the current study (2014–2016) was over three times higher than what was previously reported (1968–1969)23. We are unsure why this is the case, but it could be due to a number of different factors, including a higher number of estrous females per group, younger males, or more intergroup encounters over time41.

Even though we have demonstrated that chest beats reliably convey the body size of the emitter, future studies need to show that receivers actually attend to this information. Gorilla chest beats are thought to play a key role in male–male competition allowing individuals to assess the fighting ability of competitors and thus influence whether they should initiate, escalate or retreat in intra- and intergroup contests22,31,42. Similarly, male gelada baboons (Theropithecus gelada) assess the competitive ability of rivals through vocalizations and compare it to their own, governing how they respond in contests43. Intense contact aggression between males is infrequent in gorillas, which is presumed to reflect the high costs of aggression and their ability to resolve conflicts without resorting to this high risk behaviour (within-group31,42; between-group44). We expect that chest beats to also play a critical role in mate choice22,28,45, providing females with information about the size of the males in their own group and in neighbouring groups, which may influence their decision to transfer to another group. Larger alpha males lead groups with more adult females than smaller males, strongly suggesting that females actively chose to transfer into groups with large alpha males29,30,31. Gorillas may be similar to red deer hinds in their ability to discriminate between the acoustic signals of their current harem-holder stag and those of neighbouring stags46. Lastly, because chest beats can be heard over long-distances, we predict that both male size and the number of different males emitting chest beats are two important factors influencing group movement. Recent work in Bwindi mountain gorillas speculated that one of the functions of chest beats is to mediate how groups use space, with smaller groups with fewer adult males likely avoiding larger ones with more males, which would help to explain their findings that larger groups having more exclusive home ranges and core areas than smaller groups47.

We found no support for body size to influence the duration of chest beats, the number of beats, or the beat rate. Acoustic signals are thought to be energetically expensive to produce34,35,36,37 and we expected chest beats to be as well, with anecdotal accounts of gorillas that emit a high frequency of chest beats showing signs of exhaustion (personal observation). This is in contrast to studies of savannah baboons (Papio ursinus), showing that males with higher competitive ability produce longer vocalizations than weaker ones48,49. It is possible that the duration of chest beats (and the beat rate) decreases over time during periods of high chest beating frequency, and this decrease may be stronger in smaller males. In general the relationship between body size and the duration of vocalizations and other acoustic sounds has been understudied in mammals4,50.

In addition to conveying information on body size (and other phenotypic traits), we would expect it to be important for chest beats to be individual-specific, thereby allowing receivers to discriminate the identity of the emitter. Further study is needed to determine if there are individual signatures to the chest beats. Interestingly, we found smaller within-individual than between-individual coefficients of variation, particularly for chest beat duration and number of beats (39.0 vs. 85% and 31.6 vs. 67.9%, respectively). Notably, several temporal aspects of non-vocal drumming displays by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) and great spotted woodpeckers (Dendrocopos major) show significant individual variation, similar to many vocalizations in a wide range of species19,51,52. For example, the buttress drumming of individual chimpanzees significantly differ in the mean duration and the mean number of beats52,53.

The gorilla chest beat has both an acoustic and visual component, making it a multimodal signal. Individuals in visual proximity can benefit from seeing and hearing the gorilla emitting the chest beat, whereas individuals further away rely on the acoustic component. Researchers have been interested in determining whether the different components of multimodal signals convey the same (redundant signal or backup hypothesis) or different information (multiple messages hypotheses)54. Gorillas live in tropical forests with dense vegetation, meaning that it is often difficult to see conspecifics even if they are close by. Therefore, we argue that the evolution of the chest beat as a multimodal signal is at least in part to enhance signal transmission in an environment with limited visibility. We would expect the same messages to be transmitted in both visual and acoustic modalities, which would provide support for the redundant signal hypothesis. However, these two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, as the chest beat signal may transmit additional information, other than body size, which is then repeated in the visual and acoustic modalities, providing support for both hypotheses.

Methods

Ethics statement

This observational study was done in accordance with guidelines of the Rwanda Development Board, Rwanda Ministry of Education, Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and adhered to all laws of Rwanda.

Study population and behavioural data collection

The behavioural data collection was conducted on 25 wild, adult male silverback gorillas (older than 12 years) habituated to human observers, between January 2014 and July 2016, from ten social groups monitored by the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund’s Karisoke Research Center, Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda (Table 1). We conducted focal animal sampling periods of approximately 50 min duration to record all agonistic behaviour (aggressive displays and any form of contact aggression), noting the identity of the male who initiated the interaction31,55. The focus here was on the aggressive displays involving a chest beat that were directed at conspecifics. These data were then used to calculate a chest beat rate per male.

Sound recordings

We opportunistically collected sound recordings of silverback chest beats using a Sennheiser ME66 shotgun microphone and K6 power module with a MZW 66 windshield and a Zoom H4n recorder (Zoom corp., Tokyo, Japan). Chest beats were recorded at a sampling frequency of 96 kHz and sampling accuracy was 24-bit. Recording sensitivity was set at 80 for the duration of the study. Due to the logistically challenging nature of collecting sound recordings, we focused on six adult males from two social groups (PAB and TIT) between November 2015 and July 2016. We obtained a total of 36 chest beat sound recordings from six males (Table 2). In addition to the identity of the male that emitted the chest beat (sender), we also recorded the distance (using a distance meter; Leica Disto E7400x, Leica Geosystems AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) and the orientation of the sender with respect to the microphone to verify that these parameters did not influence peak frequency in any meaningful way. Neither the distance nor the orientation significantly correlated with peak frequency (distance: rp = − 0.069; t = − 0.400; df = 33; p = 0.692; orientation: rs = − 0.120; S = 7996.3; p = 0.493, respectively).

Body size

We used the parallel laser method56 to measure back breadth, defined as the maximum distance across the shoulders, including the rounded portion of the arms (for details see Galbany et al.57; Wright et al.31; Table 1; in addition to back breadth we also repeated the analyses using crest-back score, a composite measure combining back breadth and crest height31—see Supplementary Note). Measurements were obtained from an average of ten photos (range 3—24) per individual, totaling 507 photos of 25 males.

Acoustic analyses

Acoustic analyses focused only on the non-vocal component of the gorilla chest beat display (drumming vibrations emanating from the beating of the chest). Recordings were down-sampled for analysis to 48 kHz sampling frequency and 16-bit sampling accuracy. Individual claps (beats) were identified as intensity spikes and marked in an annotation file (Fig. 3). Peak frequency was chosen as a single transparent measure to account for an observable frequency band of higher energy mainly between 500 and 1500 Hz21 (see Supplementary Methods and Fig. S1). The median peak frequency per chest beat was measured as frequency values of maximal intensity within the “fast Fourier transform spectrum” spectra over a 30 ms bandpass filtered window (50 to 2500 Hz) starting 5 ms prior to beat onset using the Praat software58.

Statistical analyses

Peak frequency

To test the hypothesis of a significant negative correlation between body size and peak frequency we fitted a linear mixed effects model with Gaussian error and identity link. The response variable was the median peak frequency of each chest beat sequence (i.e., one final medianized data point per recording). The main predictor variable was back breadth. We included age as a control predictor and male identity as a random effect.

Duration, number of beats and beat rate

We then fitted three additional models examining the temporal characteristics of chest beats with the same structure with regard to the fixed effects, random effect and error structure as above but differing in the response variable. The first of these tested the prediction that larger males have significantly longer chest beat sequences than smaller ones. The response variable was therefore the duration of the chest beat (log-transformed). Next, we examined the prediction that larger males incorporated significantly more beats in their chest beats and have a faster beat rate than smaller males. In both these models the response variable was the number of beats during each chest beat. In the later model we also accounted for the duration of the chest beat sequence by including it as a control predictor.

The analyses were conducted in R (version 4.0.0)59 using the functions “lmer” of the “lme4” package60. Continuous predictors were z-transformed (to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1). We checked for normally distributed and homogenous residuals by visually inspecting qqplots and residuals plotted against fitted values. We verified that collinearity between age and body size was not an issue, by checking variance inflation factors (VIF) using the “vif” function from the “car” package (max VIF in all models was 1.2)61. We examined model stability by re-fitting the models after excluding levels from male identity one at a time, and comparing the estimates derived from these models with the estimates from the original model. No stability issues were found with regard to the main test predictor. The p-value for the main test predictor, body size, was computed using a likelihood ratio test comparing a full model with a reduced model not comprising this variable. Confidence intervals (95%) were determined using the function “bootMer” of the lme4 package60.

Data availability

All data will be made fully available on reasonable request.

References

Andersson, M. Sexual Selection (Princeton University Press, 1994).

Bradbury, J. W. & Vehrencamp, S. L. Principles of Animal Communication (Sinauer Associates, 1998).

Maynard Smith, J. & Harper, D. A. Animal Signals (Oxford Univ, 2003).

Fitch, W. T. & Hauser, M. D. Unpacking “Honesty”: Vertebrate vocal production and the evolution of acoustic signals. In Acoustic Communication Vol. 16 (eds Simmons, A. M. et al.) 65–137 (Springer, 2003).

Reby, D. & McComb, K. Anatomical constraints generate honesty: Acoustic cues to age and weight in the roars of red deer stags. Anim. Behav. 65, 519–530 (2003).

Liebal, K. Primate Communication: A Multimodal Approach (Cambridge University, 2014).

Taylor, A. M. & Reby, D. The contribution of source–filter theory to mammal vocal communication research. J. Zool. 280, 221–236 (2010).

Zahavi, A. Mate selection—A selection for a handicap. J. Theor. Biol. 53, 205–214 (1975).

Higham, J. P. How does honest costly signaling work?. Behav. Ecol. 25, 8–11 (2014).

Fitch, W. T. Vocal tract length and formant frequency dispersion correlate with body size in rhesus macaques. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 1213–1222 (1997).

Harris, T. R., Fitch, W. T., Goldstein, L. M. & Fashing, P. J. Black and white colobus monkey (Colobus guereza) roars as a source of both honest and exaggerated information about body mass. Ethology 112, 911–920 (2006).

Vannoni, E. & McElligott, A. G. Low frequency groans indicate larger and more dominant fallow deer (Dama dama) males. PLoS ONE 3, e3113 (2008).

Charlton, B. D. et al. Cues to body size in the formant spacing of male koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) bellows: Honesty in an exaggerated trait. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3414–3422 (2011).

Charlton, B. D., Zhihe, Z. & Snyder, R. J. The information content of giant panda, Ailuropoda melanoleuca, bleats: Acoustic cues to sex, age and size. Anim. Behav. 78, 893–898 (2009).

Wyman, M. T. et al. Acoustic cues to size and quality in the vocalizations of male North American bison, Bison bison. Anim. Behav. 84, 1381–1391 (2012).

Sanvito, S., Galimberti, F. & Miller, E. H. Vocal signalling of male southern elephant seals is honest but imprecise. Anim. Behav. 73, 287–299 (2007).

Reber, S. A. et al. Formants provide honest acoustic cues to body size in American alligators. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–11 (2017).

Budka, M. & Osiejuk, T. S. Formant frequencies are acoustic cues to caller discrimination and are a weak indicator of the body size of corncrake males. Ethology 119, 960–969 (2013).

Garcia, M., Charrier, I., Rendall, D. & Iwaniuk, A. N. Temporal and spectral analyses reveal individual variation in a non-vocal acoustic display: The drumming display of the ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus, L.). Ethology 118, 292–301 (2012).

Randall, J. A. Drummers and stompers: Vibrational communication in mammals. In The Use of Vibrations in Communication: Properties, Mechanisms and Function Across Taxa (ed. O’Connel-Rodwell, C.) 99–120 (Transworld Research Network, 2010).

Bro-Jørgensen, J. & Dabelsteen, T. Knee-clicks and visual traits indicate fighting ability in eland antelopes: Multiple messages and back-up signals. BMC Biol. 6, 47 (2008).

Schaller, G. B. The Mountain Gorilla—Ecology and Behavior (University of Chicago Press, 1963).

Fossey, D. Vocalizations of the mountain Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla beringei). Anim. Behav. 20, 36–53 (1972).

Perlman, M. & Salmi, R. Gorillas may use their laryngeal air sacs for whinny-type vocalizations and male display. J. Lang. Evol. 2, 126–140 (2017).

Harcourt, A. H. & Stewart, K. J. Gorilla Society: Conflict, Compromise, and Cooperation Between the Sexes (University of Chicago Press, 2007).

Robbins, M. M. Gorillas: diversity in ecology and behavior. In Primates in Perspective (eds Campbell, C. J. et al.) 326–339 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Sicotte, P. Females mate choice in mountain gorillas. In Mountain Gorillas: Three Decades of Research at Karisoke (eds Robbins, M. M. et al.) 59–87 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001).

Robbins, M. M. Behavioral aspects of sexual selection in mountain gorillas. In Sexual Selection & Reproductive Competition in Primates: New Perspectives and Directions (ed. Jones, C. L.) 477–501 (American Society of Primatologists, 2003).

Breuer, T., Robbins, A. M., Boesch, C. & Robbins, M. M. Phenotypic correlates of male reproductive success in western gorillas. J. Hum. Evol. 62, 466–472 (2012).

Caillaud, D., Levréro, F., Gatti, S., Ménard, N. & Raymond, M. Influence of male morphology on male mating status and behavior during interunit encounters in western lowland gorillas. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 135, 379–388 (2008).

Wright, E. et al. Male body size, dominance rank and strategic use of aggression in a group-living mammal. Anim. Behav. 151, 87–102 (2019).

Morton, E. S. On the occurrence and significance of motivation-structural rules in some bird and mammal sounds. Am. Nat. 111, 855–869 (1977).

Bowling, D. L. et al. Body size and vocalization in primates and carnivores. Sci. Rep. 7, 41070 (2017).

Clutton-Brock, T. H. & Albon, S. D. The roaring of red deer and the evolution of honest advertisement. Behaviour 69, 145–170 (1979).

Wich, S. A. & Nunn, C. L. Do male ‘long-distance calls’ function in mate defense? A comparative study of long-distance calls in primates. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 52, 474–484 (2002).

Ryan, M. J. Energy, calling, and selection. Integr. Comp. Biol. 28, 885–898 (1988).

Vehrencamp, S. L., Bradbury, J. W. & Gibson, R. M. The energetic cost of display in male sage grouse. Anim. Behav. 38, 885–896 (1989).

Starck, D., Schneider, R. & Respirationsorgane, A. Larynx. Primatologia 3, 423–587 (1960).

Fitch, W. T. Vertebrate bioacoustics: Prospects and open problems. In Vertebrate Sound Production and Acoustic Communication Vol. 53 (eds Suthers Simmons, R. A. et al.) 297–328 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Salmi, R. & Muñoz, M. The context of chest beating and hand clapping in wild western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Primates 61, 225–235 (2020).

Caillaud, D. et al. Violent encounters between social units hinder the growth of a high-density mountain gorilla population. Sci. Adv. 6, 724 (2020).

Robbins, M. M. Male-male interactions in heterosexual and all-male wild mountain gorilla groups. Ethology 102, 942–965 (1996).

Benítez, M. E., Pappano, D. J., Beehner, J. C. & Bergman, T. J. Evidence for mutual assessment in a wild primate. Sci. Rep. 7, 2952 (2017).

Mirville, M. O. et al. Factors influencing individual participation during intergroup interactions in mountain gorillas. Anim. Behav. 144, 75–86 (2018).

Breuer, T., Robbins, A. M. & Robbins, M. M. Sexual coercion and courtship by male western gorillas. Primates 57, 29–38 (2016).

Reby, D., Hewison, M., Izquierdo, M. & Pépin, D. Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Hinds discriminate between the roars of their current harem-holder stag and those of neighbouring stags. Ethology 107, 951–959 (2001).

Seiler, N. & Robbins, M. M. Using long-term ranging patterns to assess within-group and between-group competition in wild mountain gorillas. BMC Ecol. 20, 40 (2020).

Kitchen, D. M., Seyfarth, R. M., Fischer, J. & Cheney, D. L. Loud calls as indicators of dominance in male baboons (Papio cynocephalus ursinus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 53, 374–384 (2003).

Fischer, J., Kitchen, D. M., Seyfarth, R. M. & Cheney, D. L. Baboon loud calls advertise male quality: Acoustic features and their relation to rank, age, and exhaustion. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 56, 140–148 (2004).

Ey, E., Pfefferle, D. & Fischer, J. Do age- and sex-related variations reliably reflect body size in non-human primate vocalizations? A review. Primates 48, 253–267 (2007).

Budka, M., Deoniziak, K., Tumiel, T. & Woźna, J. T. Vocal individuality in drumming in great spotted woodpecker—A biological perspective and implications for conservation. PLoS ONE 13, 2 (2018).

Arcadi, A. C., Robert, D. & Boesch, C. Buttress drumming by wild chimpanzees: Temporal patterning, phrase integration into loud calls, and preliminary evidence for individual distinctiveness. Primates 39, 505–518 (1998).

Babiszewska, M., Schel, A. M., Wilke, C. & Slocombe, K. E. Social, contextual, and individual factors affecting the occurrence and acoustic structure of drumming bouts in wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 156, 125–134 (2015).

Fröhlich, M. & van Schaik, C. P. The function of primate multimodal communication. Anim. Cogn. 21, 619–629 (2018).

Altmann, J. Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour 49, 227–267 (1974).

Bergeron, P. Parallel lasers for remote measurements of morphological traits. J. Wildl. Manag. 71, 289–292 (2007).

Galbany, J. et al. Body growth and life history in wild mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) from Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 163, 570–590 (2017).

Boersma, P. & Weenink, D. Praat: doing phonetics by computer [Computer program] (2020). Version 6.1.36, retrieved 6 December 2020 from http://www.praat.org/.

R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. (2015).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression (Thousand Oaks, 2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Rwanda Development Board and the Rwandan Ministry of Education for permission to conduct the research. We are indebted to everyone at the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International’s Karisoke Research Center for their continued work on the protection, monitoring and research of the gorillas. Particular thanks go to the research technicians who contributed data to this project and Winnie Eckardt for helpful discussion on the project. This research was funded by the Max Planck Society, National Geographic Society, The Columbian College of The George Washington University, The Wenner-Gren Foundation (ICRG-123), the National Science Foundation (BCS1520221) and The Leakey Foundation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.W. designed the study, collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.G. conducted the acoustic analysis, and contributed to the writing of the methods. E.N. collected data and edited the manuscript. J.G. contributed data and edited the manuscript. S.M. contributed data and edited the manuscript. T.S. contributed data and edited the manuscript. M.R. designed the study and helped with writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, E., Grawunder, S., Ndayishimiye, E. et al. Chest beats as an honest signal of body size in male mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei). Sci Rep 11, 6879 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86261-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86261-8

This article is cited by

-

Clap, Clap, Clap - Unsystematic Review Essay on Clapping and Applause

Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science (2023)

-

Ordinaries 10

Journal of Bioeconomics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.