Abstract

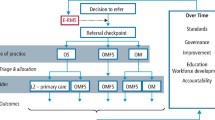

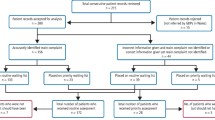

Referrals are defined as ‘a process in which a health worker at one level of the health system, having insufficient resources (drugs, equipment, skills) to manage a clinical condition, seeks the help of a better or differently resourced facility at the same or higher level to assist in patient management'. Within the UK, the NHS dental service is divided into nationally defined levels of care, which provide treatment based upon complexity and patient modifying factors. Having a sound knowledge of these levels will help general dental practitioners (GDPs) make appropriate and efficient onward referrals to the correct service.

This article aims to outline the key information required for all strong GDP referrals, as well as highlighting information that may be specific to each speciality. This is with the hope of creating a key list for GDPs to use on clinic when writing referrals to reduce the incidence of missed information and subsequent rejection. The article also aims to outline the levels of NHS dental care and what factors and treatments are suitable for each to aid GDPs during their referral decision-making process.

Key points

-

Explores key criteria which need to be included in all dental referral letters.

-

Highlights different levels of care in dentistry based on treatment complexity and patient factors.

-

Explores essential criteria needed for different specialities, optimising patient care.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 24 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $10.79 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organisation. Hospitals. 2023. Available at https://www.who.int/health-topics/hospitals#tab=tab_1 (accessed November 2023).

General Dental Council. Standards for the Dental Team. 2013. Available at https://standards.gdc-uk.org/Assets/pdf/Standards%20for%20the%20Dental%20Team.pdf (accessed November 2023).

UK Government. Handbook to the NHS Constitution for England. 2023. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/supplements-to-the-nhs-constitution-for-england/the-handbook-to-the-nhs-constitution-for-england (accessed November 2023).

Djemal S, Chia M, Ubaya-Narayange T. Quality Improvements of referrals to a department of restorative dentistry following the use of a referral proforma by referring practitioners. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 85-88.

Care Quality Commission. Dental mythbuster 20: using language professionals and interpreters. 2023. Available at https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-providers/dentists/dental-mythbuster-20-using-interpreters-language-british-sign-language (accessed November 2023).

UK Government. The Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 2017. 2017. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/1322/regulation/9/made (accessed November 2023).

NHS England. Pan-London Endodontic Referrals and Level 2 Service Provision. 2019. Available at https://www.stgeorges.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/2.-Pan-London-endodontic-referral-criteria-April-2019.pdf (accessed November 2023).

NHS England. Introductory Guide for Commissioning Dental Specialities. 2015. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/intro-guide-comms-dent-specl.pdf (accessed January 2024).

NHS England. Managed Clinical Network Terms of Reference. 2017. Available at https://www.surreyldc.org.uk/files/blog/2017/Aug17_MCN_Chair_Opportunity/MCN-Chair-ToRs-Aug17.pdf (accessed November 2023).

NHS England. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 - First Release. 2010. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-dental-health-survey/adult-dental-health-survey-2009-first-release (accessed April 2024).

American Society of Anesthesiologists. Statement on ASA Physical Status Classification System. 2020. Available at https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-practice-parameters/statement-on-asa-physical-status-classification-system (accessed November 2023).

British Society of Periodontology. BSP Guidelines for Periodontal Patient Referral. 2020. Available at https://www.bsperio.org.uk/assets/downloads/BSP_Guidelines_for_Patient_Referral_2020.pdf (accessed November 2023).

British Society of Periodontology. Implementing the 2017 Classification of Periodontal Diseases to Reach a Diagnosis in Clinical Practice. 2018. Available at https://www.bsperio.org.uk/assets/downloads/111_153050_bsp-flowchart-implementing-the-2017-classification.pdf (accesses November 2023).

Astrom A N, Smith O R, Sulo G. Early-life course factors and oral health among young Norwegian adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2020; 49: 55-62.

International Association of Dental Traumatology. 2020 IADT Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries. 2020. Available at https://www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org/for-professionals.html (accesses November 2023).

NHS England. Guidance notes on Paediatric Referrals - Pan London; effective from 1 April 2017. 2017. Available at https://www.bromleyhealthcare.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Appendix-1-Guidance-notes-on-Paediatric-Referrals_1.pdf (accessed November 2023).

British Orthodontic Society. Quick Reference Guide to Orthodontic Assessment and Treatment. 2022. Available at https://www.bos.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Ortho-referral-quick-reference-sheet-final-post-BOS-2019-v2.pdf (accesses November 2023).

NHS England. Guides for commissioning dental specialities - Orthodontics. 2015. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-orthodontics.pdf (accessed November 2023).

NHS England. Commissioning Standard for Restorative Dentistry. 2019. Available at https://allcatsrgrey.org.uk/wp/download/dental_health/commissioning-standard-for-restorative-dentistry.pdf (accessed November 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. 2023. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng12/resources/suspected-cancer-recognition-and-referral-pdf-1837268071621 (accessed November 2023).

NHS England. Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine. 2015. Available at https://www.dental-referrals.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/guid-comms-oral.pdf (accessed November 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidance on the extraction of wisdom teeth. 2002. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta1 (accessed November 2023).

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Management of Dental Patients Taking Oral Anticoagulants or Antiplatelet Drugs. 2022. Available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/anticoagulants-and-antiplatelets/ (accessed November 2023).

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Oral Health Management of Patients Prescribed Bisphosphonates. 2011. Available at https://www.sdcep.org.uk/published-guidance/bisphosphonates/ (accessed November 2023).

NHS England. Guidance notes on Special Care Dentistry Referrals - Pan London. 2023. Available at https://www.kch.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/rf-088.1-guidance-notes-for-special-care-dentistry-referrals.pdf accessed November 2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hannah Gorman and Kishan Patel discussed together the ideas for the article. Hannah Gorman drafted the initial manuscript with contributions from Kishan Patel. All authors revised draft versions of the manuscript and gave approval for the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gorman, H., Patel, K. Optimising referral letters for the dental practitioner. Br Dent J 236, 688–692 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7338-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7338-3