Abstract

The ability to experience pleasurable sexual activity is important for human health. Receptive anal intercourse (RAI) is a common, though frequently stigmatized, pleasurable sexual activity. Little is known about how diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus and their treatments affect RAI. Engaging in RAI with gastrointestinal disease can be difficult due to the unpredictability of symptoms and treatment-related toxic effects. Patients might experience sphincter hypertonicity, gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety, altered pelvic blood flow from structural disorders, decreased sensation from cancer-directed therapies or body image issues from stoma creation. These can result in problematic RAI — encompassing anodyspareunia (painful RAI), arousal dysfunction, orgasm dysfunction and decreased sexual desire. Therapeutic strategies for problematic RAI in patients living with gastrointestinal diseases and/or treatment-related dysfunction include pelvic floor muscle strengthening and stretching, psychological interventions, and restorative devices. Providing health-care professionals with a framework to discuss pleasurable RAI and diagnose problematic RAI can help improve patient outcomes. Normalizing RAI, affirming pleasure from RAI and acknowledging that the gastrointestinal system is involved in sexual pleasure, sexual function and sexual health will help transform the scientific paradigm of sexual health to one that is more just and equitable.

Key points

-

Receptive anal intercourse (RAI) is common worldwide.

-

Pleasurable RAI occurs through stimulation of the perianal or anal nerves and prostate or paraurethral glands, inducing vasodilation, erectile tissue engorgement, anopelvic tissue sensitization, and anal sphincter and pelvic muscular contractions.

-

Patients with a stoma and anorectal stump should be counselled on hygiene and dilator use to minimize infections, maintain anorectal patency, and prevent a permanent stoma, promoting RAI restoration.

-

Antidiarrhoeals, anti-flatulence medications, fibre supplements, lower residue diet to control regularity, avoiding spicy foods, timing meals, and defecation prior to RAI can help control symptoms and relieve distress.

-

Survivors of anal, rectal, and colon cancer and patients with gastrointestinal disease should be counselled on problematic RAI due to anal sphincter, neurovasculature, and prostate or paraurethral gland damage resulting in arousal dysfunction, anodyspareunia or orgasm dysfunctions.

-

Management strategies, including anal dilators for anodyspareunia, anal vibrators for arousal disorders, pelvic floor strengthening for anorgasmia and psychological interventions for decreased desire, should be discussed with patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintaining the capacity for consensual and pleasurable sexual activity is an essential component of human health and a fundamental human right1,2,3. Despite being a pleasurable sexual activity4, anal intercourse, particularly receptive anal intercourse (RAI) — defined here as stimulation of the anus by a phallus, finger, object (such as dildo), tongue or mouth — is stigmatized and often not acknowledged by health-care professionals5,6. Moreover, RAI is criminalized and even punishable by death in many countries and territories7,8,9.

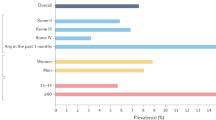

Nonetheless, RAI is common worldwide10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Up to 81% of cisgender gay and bisexual men10, 20–46% of cisgender women10,28 (including cisgender heterosexual29, lesbian30 and bisexual30 women), 80% of transgender women (or transfeminine people)31,32 and 28% of transgender men (or transmasculine people)33 engage in RAI. For intersex people and individuals with differences of sex development34, RAI is a major source of erogenous sensation and pleasure — particularly for those who had genitopelvic surgery at birth resulting in decreased genital sensations35. Additionally, up to 3% of cisgender heterosexual men have engaged in RAI with a phallus36 (likely underestimated due to associated stigma37), up to 27% of cisgender heterosexual women and 13% of cisgender heterosexual men have engaged in RAI through anal stimulation by tongue or mouth (termed analingus or ‘rimming’) in the past month38, and up to 17% of people have engaged in RAI through a dildo attached to a sexual partner39,40 (termed ‘pegging’)41.

In RAI, the anal canal, perianal skin, prostate or paraurethral glands, erectile tissues, pelvic floor muscles, and supplying neurovasculature facilitate pleasure4,42,43. Diseases of the colon, rectum and anus (including disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBI), structural diseases such as haemorrhoids, infectious diseases, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and malignancies) and their treatments (surgical resections, ostomy formation, anal closures, pelvic radiation and systemic therapies, among others) can adversely affect these anatomical structures and sexual function. However, research has largely equated sexual function with penile erections, vaginal intercourse and reproduction44,45,46,47,48,49,50, neglecting the effects of diseases and their treatments on people who engage in RAI4,36,51. Moreover, RAI is interconnected with diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. For example, anal cancer can develop through human papillomavirus (HPV) transmission during RAI52 and aggressive force during RAI can lead to structural gastrointestinal disorders such as anal fissures53.

Research on problematic RAI — encompassing anodyspareunia (painful RAI), arousal dysfunction, orgasm dysfunction and/or decreased sexual desire — due to gastrointestinal diseases and their treatments is lacking. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network acknowledges that RAI is a risk factor for anal cancer54, that anal cancer is more common in cisgender gay and bisexual men than in the general population54 (with anal cancer incidence being approximately 20–80 times higher in gay and bisexual men than in the general population)55, and that sexual dysfunction is among the most distressing toxic effects of cancer treatment54. Unfortunately, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines fail to acknowledge problematic RAI as a distressing outcome or to offer guidance for engaging in RAI after cancer treatments54. Similarly, a survey of 426 members of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology found that 70% of gastroenterologists never or infrequently discuss sexual dysfunction with their patients; by contrast, 70% of patients believe that their gastroenterologist should be able to manage their sexual dysfunction56. Strikingly, the survey completely omits RAI. To address the health-care inequities for people who engage in RAI, it is necessary for health-care professionals to acknowledge pleasurable and problematic RAI4,56,57.

In this Review, we detail the role of anatomy, neurophysiology and microbiota in pleasurable RAI to provide a framework for understanding problematic RAI. We highlight the influence of DGBI, structural diseases, infectious diseases, inflammatory diseases and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus as well as their associated treatments on RAI. We then discuss management, mitigation and treatment strategies for disease and treatment-related problematic RAI. Overall, this Review seeks to normalize RAI and transform the scientific paradigm of sexual health to one that is more just and equitable.

Pleasurable RAI

The number of people engaging in RAI (Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Box 1) is increasing58,59,60, including a ~5% per decade increase in the UK58 and Australia59,60, potentially corresponding to worldwide cultural and demographic changes such as an increase in the number of people self-identifying as an individual from a sexual and gender minority community61,62,63. Despite this observation, most health-care workers do not routinely discuss, or even acknowledge, RAI23,64,65 due to a lack of RAI-specific health education66 and the cultural stigma5,6,7,8,9,67. The few existing educational programmes address RAI as it relates to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and harm reduction5,6.

Schematics represent stereotypical anatomy and are provided for general insights into anatomical structures of complex anatomy. a, Representative sagittal image illustrating the genitopelvic anatomy of a cisgender woman experiencing pleasurable receptive anal intercourse (RAI) with a phallus. During RAI, pressure on the cavernous nerves (located between the vagina and rectum)419, paraurethral glands, cervix, posterior bulboclitoris (clitoris and vestibular bulbs)420,421,422, and anus will elicit pleasure and reflexive external anal sphincter contractions96,97,423. Pressure on the cavernous nerves will induce flow into the vestibular bulbs and cause bulboclitoris enlargement424. Engorgement of the vestibular bulbs and crura will additionally induce pressure on the glans, resulting in pleasure and anal sphincter contractions through the bulbocavernous reflex89,97,425. Thrusting in the anus can cause pressure on the vestibular glands and movement of the bulboclitoris, ultimately inducing pleasure, lubrication and pelvic muscle contractions. Movement of the paraurethral glands and bulboclitoris can further stimulate the surrounding nerves to induce anal sphincter and pelvic muscle contraction91. During receptive intercourse, the bulboclitoris will move and stimulate the surrounding nerves to induce pleasure420. Simultaneously, the clitoral bulbs, along with surrounding pelvic structures, become engorged with blood, stabilizing the vagina, anus and paraurethral glands426. As the pelvic and erectile structures fill with blood and the genitopelvic anatomy fixates and sensitizes, movement during RAI will become more pleasurable426. Sustained repetition can result in orgasm427. b, Representative sagittal image illustrating the genitopelvic anatomy of a cisgender man experiencing pleasurable RAI with a tongue and mouth. During RAI, stimulation of the perianal skin and anus will elicit reflex external anal sphincter contraction, and stimulation and movement of the deep portion of the penis (rather than the pendulous part) and prostate will stimulate the pudendal nerve95 and/or cavernous nerves (located between the prostate and rectum419) and elicit reflex external anal sphincter contractions, causing pleasure, erection, ejaculation and orgasm96,97,423. Sustained repetitive activation of these sensory circuits during RAI can continue to build and intensify, which can ultimately lead to orgasm427. c, Representative sagittal image illustrating the genitopelvic anatomy of a transmasculine person experiencing pleasurable RAI with fingers. In transmasculine people who have undergone metoidioplasty428,429 and/or phalloplasty, pleasure from RAI occurs through the stimulation of cavernous nerves and surrounding erectile tissues, paraurethral tissues, perianal skin, and cervix. For those who have undergone metoidioplasty428,429, tactile stimulation of the neophallus might cause a reflex reaction through the dorsal clitoral nerves. For those who have undergone a phalloplasty430,431,432, direct tactile stimulation of the natal clitoris at the base of the neophallus and indirect stimulation through movement of the phallus might cause a reflex reaction through the tissue flap to the dorsal clitoral nerve anastomoses433,434. d, Representative sagittal image illustrating the genitopelvic anatomy of a transfeminine person experiencing pleasurable RAI with an attachable dildo. The reconstructed neurovascular pedicle flap for neoclitoral sensation (which contains the preserved dorsal penile nerves) and a reconstructed neolabia (which might contain the dorsal penile nerves and posterior scrotal nerve innervation) facilitate pleasurable intercourse for patients with zero-depth and full-depth neovaginas435,436. Stimulation of the prostatic and neoclitoral or neolabial neurovasculature will elicit afferent sensory impulses, with reflex efferent impulses causing contraction of the anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles. Notably, these muscles (the bulbospongiosus and/or the ischiocavernosus) might be partially or completely resected during vaginoplasty435. Further details are available in Supplementary Box 1. Adapted from ref. 4, Springer Nature Limited.

Schematics represent stereotypical genitopelvic neuroanatomy and are provided for general insights into complex structures in cisgender women and transmasculine people (part a) and cisgender men and transfeminine people (part b). Pressure on the anopelvic structures will elicit pleasure, orgasm and external anal sphincter contraction through distinct neural pathways (red: afferent pathway; blue: efferent pathway), resulting in reflex external anal sphincter contraction, which will place pressure on the finger, phallus, object (for example, dildo, vibrator) or tongue of a partner, increasing dyadic arousal, intimacy and pleasure. Further details are available in Supplementary Box 1. Adapted from ref. 4, Springer Nature Limited.

The absence of RAI (and particularly its relation to pleasure) in medical training and sexual education66 results in a lack of information and resources for people engaging in RAI. Additionally, the systemic omission of RAI from medicine and health care might contribute to patient reluctance to initiate discussions and hesitation to seek health-care guidance on RAI as well as in an increase in potential patient harm during RAI66 and the stigma68, including RAI criminalization5,6,7,8,9, everyday colloquialisms (for example, use of the word ‘butthurt’ to critique an overly sensitive person69,70), and negative judgements of the receptive partner (‘bottom’) but not of the insertive partner (‘top’) in anal intercourse (termed ‘bottom-shaming’66,67,71).

To effectively discuss RAI (Fig. 3) and counsel patients on the effects of gastrointestinal diseases and their treatment on RAI, it is essential to destigmatize and normalize RAI and understand it as it relates to pleasure72 — specifically the genitopelvic anatomy, physiology and gut microbiology involved in facilitating pleasurable RAI.

To address medical inequities for individuals engaging in receptive anal intercourse (RAI), health-care providers should proactively engage in open conversations with colleagues, friends and family to learn inclusive language437 and gain awareness of the diverse lived experiences. Then, when interacting with a patient, one can more easily adapt terminology and tone to ensure patient comfort to prevent potential delays in care438. Discussing sexual orientation, gender identity and sex recorded at birth with a patient is a necessary step before asking about preferred sexual behaviours, gender-affirming hormone therapies and genital anatomy439,440,441,442,443. Gathering this information can not only strengthen the physician–patient relationship but also influence accurate diagnoses and treatment recommendations405,444. If a patient does engage in RAI, centring the conversation on pleasure can enhance patient comfort and encourage disclosure of medical concerns5,6,72. Emphasizing pleasure should include a discussion about disease and treatment effects, supporting informed decision-making and improving quality of life445,446 and health outcomes447,448,449,450. Subsequently, a conversation about best practice and safety during RAI should occur and cover anorectal douching, lubricant, alkyl nitrites (termed ‘poppers’) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Educating patients about potential interactions between ‘poppers’ and medications (for example, phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors) is vital to prevent adverse cardiovascular events. Iso-osmolar lubricants (typically silicone based) might be preferred for RAI as hyperosmolar lubricants (typically water based) can induce epithelial damage and increase risk of bleeding and infection374,375,376. However, caution is advised when using silicone lubricant with silicone objects (for example, dildo). STI screening and treatment should be addressed in relation to sexual practices rather than specific populations451 to ensure inclusive and personalized recommendations375. Importantly, STIs affecting the anorectum might be asymptomatic210, and there might be a risk of transmitting protozoal infections (for example, Giardia intestinalis) and enteropathogenic bacterial infections (for example, Escherichia coli) during RAI through oral–anal stimulation and indirect contamination of objects used during intercourse or fingers222. HPV, human papillomavirus; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Functional anatomy and physiology

Although the exact genitopelvic anatomy might differ among cisgender women, cisgender men, intersex people or individuals with differences of sex development, and gender-expansive individuals (that is, those with gender identities or expressions that are outside the gender binary determined by society), the functional anatomy involved in pleasurable RAI are embryologically homologous and functionally equivalent73 (Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Box 1). Stimulation of the nerves in the perianal skin, anus, erectile tissues, and prostate or paraurethral glands4,74, including the pudendal, hypogastric, pelvic splanchnic nerves and their associated branches74,75, helps facilitate the phases of the RAI sexual response cycle — initial excitement, plateau of arousal, orgasm and resolution76,77.

Sensory stimuli — visual, tactile or other forms — initiate excitement during RAI, leading to increased blood flow to the pelvis, which is maintained by a compensatory increase in heart and respiratory rate78. From in vitro studies of human tissues and in vivo studies with animal models79, it is well established that nitrous oxide production triggers pelvic vascular smooth muscle relaxation, enhancing regional blood flow and pelvic tissue sensitivity80,81. The pelvic muscles, erectile tissues and anus continue to become engorged with blood from branches of the internal pudendal artery82,83, enhancing nutrient delivery crucial for neuron communication84. Pressure on the cavernous nerves, located anterolateral to the anorectum (or neovagina), directly from an object (such as finger, phallus, dildo or tongue) or indirectly through the movement of surrounding structures (such as prostate or paraurethral glands, posterior erectile tissues, and vagina or neovagina) can elicit erectile tissue expansion85,86,87.

As the erectile tissues become engorged with blood, the glans (of the natal bulboclitoris (clitoris and vestibular bulbs)88, penis, neoclitoris or metoidioplasty neophallus) becomes more sensitive and, through the bulbocavernosus reflex, glans stimulation leads to external anal sphincter contractions89,90. Simultaneously direct and indirect pressure on the prostate or paraurethral glands will cause pelvic floor muscular contractions — the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles (deep perineal nerve) and external anal sphincter contraction (inferior anal nerve)91,92. Additionally, stimulation of the afferent inferior anal and perineal nerves (branches of the pudendal nerve)86,93 in the sensate anus (below the pectinate line) and adjacent skin can elicit anal sphincter contractions86,94,95 through the anocutaneous reflex nerve pathway96,97.

In contrast to the anus, rich in nerves that transduce pain and pleasure98, the rectum contains mechanoreceptor nerves that detect and translate rectal stretching into neural output98,99,100. Nevertheless, the rectum is involved in pleasurable RAI as low levels of rectal distension can activate rectal contractions and anal relaxations99,100, promote feelings of ‘rectal fullness’74 (pleasurable for many individuals engaging in RAI)74, and reflexively place pressure on a finger, phallus, attached dildo or tongue of a partner, which can increase dyadic arousal, intimacy and pleasure. As genitopelvic nerve electrical impulse signalling continues, blood flow to genitopelvic anatomy increases, organ sensitivity intensifies and RAI arousal escalates, culminating in orgasm80,81,82.

Gut microbiome and RAI

The gastrointestinal–oral and gut–microbiome axes are an important component of gastrointestinal function and gut–brain communication101. By influencing metabolite levels in the neural, endocrine and inflammatory pathways, including dopamine, serotonin, nitric oxide, hydrogen sulfide and γ-aminobutyric acid, experimental data from in vitro studies have suggested that the gut microbiome can contribute to sexual function101,102. The gut microbiome might also help maintain structural integrity103, preserve anatomical function103 and modulate intestinal permeability104, which can influence sexual health. Gut microbial dysbiosis, or an imbalanced microbiome, has been associated with anatomical abnormalities in the anus (anal sphincter hypertonicity, inflammation, anal pain and anal fistulas103,105) and sexual dysfunction106,107, which is likely multifactorial but could be due to metabolite dysregulation102 as well as anatomical dysfunction from pelvic cross-organ sensitization increasing inflammatory-related intestinal permeability104.

The oral microbiome might additionally affect sexual health108 and the relative abundance of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral microbiome might influence nitric oxide production109, essential for sexual arousal110. Thus, it is logical that oral microbial dysbiosis might cause sexual arousal dysfunction108. Awareness of how the gastrointestinal microbiome might be implicated in pleasurable and problematic RAI is important to counsel patients, provide context to disease-related and treatment-related dysfunction, and develop novel technologies.

Engaging in RAI might influence the composition of the gut microbiome111 as well as the oral microbiome112,113,114; yet, it is imperative to emphasize that RAI represents only one singular factor among numerous influences that collectively shape the microbiome of an individual115. The microbiota can be influenced by environmental factors such as pH, availability of nutrients and temperature116. Studies have suggested that people who engage in RAI might exhibit a gut microbiome with a higher ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides117 (a biomarker of diet and lifestyle, with an increased ratio corresponding to a plant-based diet118), possibly influenced by factors such as a higher fibre diet to facilitate RAI preparation119,120, the presence of Prevotella in semen121, post-RAI irritation122, aggressive douching123 and hyperosmolar lubricant use124.

Nonetheless, it is known that many factors likely contribute to the gut microbiota, including diet or antibiotic exposure, as well as to other aspects of health for which inequitable outcomes exist due to the social determinants of health115. Advances in gut–brain microbiome research have suggested that discrimination, social inequity and minority stress likely have direct influences on the gut–brain microbiome axis125,126,127. Thus, one must be cautious and never presume that the gut microbiota is influenced solely by RAI. Still, future research will hopefully provide insight into the role of the microbiome, if any, in facilitating pleasurable RAI, which might help develop interventions for problematic RAI.

Problematic RAI

Problematic RAI is characterized by pain during or after RAI (anodyspareunia), arousal dysfunction, orgasm dysfunction and/or decreased sexual desire4,128,129,130,131. The aetiology of each dysfunction subdomain is multifactorial and can result from issues with the functional anatomy and physiology involved in pleasure4,128,129. Sexual dysfunction can result from multiple factors, including gastrointestinal diseases, iatrogenic interventions (such as medications, surgery or radiation) and biopsychosocial factors4,128,129 (Fig. 4).

Diagnosing problematic receptive anal intercourse (RAI) requires a comprehensive, patient-centred approach. Establishing trust and comfort is critical; encouraging an open discussion in the patient’s own words will substantially help understand the issue. a, Asking specific questions regarding pain (timing during intercourse, location, quality), arousal (associated phallus-related symptoms), orgasm, desire (body image) and taking a comprehensive medical history can help construct a differential diagnosis. A systematic physical examination should begin with inspection, noting any visible abnormalities (such as skin changes in the genitopelvic area or anus) or devices (such as a stoma) to provide further evidence on issues with sexual desire or pain. Assessing the anus and pelvis for tenderness, swelling, or irregularities and performing focused neurological assessments by evaluating sensation and reflexes (anocutaneous96,97, bulbocavernosus89,90) can assist in differentiating the aetiology (for example, neurological, vascular, structural, psychological). The Digital Rectal Examination Scoring System (DRESS; 0 = no pressure, 3 = normal, 5 = tight) can quantify anal sphincter resting and squeeze tones452. Throughout the exam, patient engagement and communication of findings are key for patient understanding and autonomy. Additionally, it is important to discuss trauma, including intimate partner violence, and note any inconsistencies between history and physical exam196. b, Lab tests and imaging can complement clinical assessment and provide further confirmation if a diagnosis is not yet evident453,454,455,456,457. Ultimately, these steps should identify underlying physiological and anatomical factors contributing to problematic RAI to guide targeted treatment strategies. Laboratory values might reveal imbalances or underlying conditions contributing to decreased sexual desire or other aspects of problematic RAI453,454,455,456,457. Anoscopy173 can assist in the diagnosis of external structural abnormalities (for example, fissure, haemorrhoids) and endoanal ultrasonography can assess internal structural abnormalities, specifically the anal sphincters and intersphincteric plane458. MRI provides a detailed analysis of genitopelvic anatomy, uncovering issues such as pelvic floor dysfunction due to inflammation or other structural abnormalities240. Vascular studies employing Doppler ultrasonography can help evaluate blood flow to erectile and pelvic tissues, crucial for diagnosing issues with arousal459. Using fluoroscopy, MRI defecography can evaluate anorectum and pelvic floor dynamics during defection to provide insight into the neurophysiology of the anal sphincters460. Ultimately, empathetic dialogue, a comprehensive assessment and multidisciplinary collaboration among health-care professionals can enable accurate diagnosis and lead to personalized treatment and support for patients with problematic RAI. CNS, central nervous system; DGBI, disorders of gut–brain interaction; NO, nitric oxide; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Anodyspareunia and painful RAI

Criteria for the measurement of anodyspareunia — recurrent or persistent pain that occurs before, during or after RAI132 — are varied and include elements similar to those used to measure dyspareunia and vaginismus15,133,134,135. Some have advocated for a standardized clinical definition of anodyspareunia that aligns with genitopelvic pain or penetration disorders15 but criteria used in existing studies vary. A systematic review (identifying 8 studies) notes that the prevalence of anodyspareunia is difficult to assess given varying criteria among studies119; however, using a consistent definition, it is estimated to be from 12% (of n = 277) to 14% (of n = 404) in sexually active cisgender sexual minority men and 9% (of n = 505) in cisgender women engaging in RAI at least twice yearly119, potentially underestimated due to those avoiding RAI due to pain136,137.

Although RAI might initially be painful, over time, the pain generally diminishes and pleasure increases74,138. Anatomical, physiological and psychosocial factors that can contribute to painful RAI include inadequate anorectum lubrication, the anorectal angle, anal sphincter tightness, size of the penetrating object, and lack of relaxation and foreplay133,139,140,141,142. Painful RAI typically occurs at the anus during initial entry (39.6%) or during entry and/or thrusting (16.7%)143. Internal anal sphincter hypertonicity and sphincter spasms can result in difficulty with anal entry and painful RAI65. Sharp pain might additionally be experienced during RAI entry or thrusting if a penetrating object pushes on the rectosigmoid junction causing mesenteric stretching144.

Psychosocial factors, such as generalized or conditioned anxiety, trauma history (more prevalent in women and people from sexual and gender minority communities145), internalized homophobia, fear of STI transmission (including HIV), and fear and/or phobia of engaging in a stigmatized act, can increase sympathetic nervous system activity139,146 and anal sphincter hypertonicity147,148,149. Additionally, defecation concerns, including defecation during RAI, were associated with anodyspareunia in a cohort of cisgender sexual minority men without any particular medical comorbidities engaging in RAI in the 4 weeks prior (n = 135)150. Normalizing and discussing RAI, affirming pleasurable RAI, and offering mitigation strategies can help prevent unnecessary phobias and resultant pain and dysfunction135,143,151.

Arousal dysfunction

Arousal dysfunction can occur from direct damage to the functional erectile and pelvic tissues, injury to the supplying neurovasculature, or impaired blood flow preventing genitopelvic tissue engorgement4,42,152,153. During RAI, people might transiently lose an erection as other areas are stimulated and blood is diverted from erectile tissues; however, diseases and treatment-related sequelae can further shunt blood flow away from pelvic and erectile structures, further decreasing arousal and ultimately delaying orgasm or altogether preventing it4,42.

Orgasm dysfunction

Orgasm dysfunctions include dysorgasmia and anorgasmia4,154. In RAI, the anal sphincters and levator ani are important for facilitating arousal and orgasm155,156 by squeezing an inserted object and helping it apply pressure on the sensate pelvic structures during RAI155. During orgasm, the pelvic floor muscles, including the anal sphincters, contract rhythmically77. Decreased pelvic floor and anal sphincter muscle strength is associated with anorgasmia155,156,157, whereas overactive and inflamed pelvic floor and anal sphincter muscles are associated with dysorgasmia in all people158,159. Thus, damage to the anal sphincters and pelvic floor muscles contributes to orgasm dysfunction in RAI.

Decreased sexual desire

Gastrointestinal diseases and their treatments commonly influence body image and self-esteem, which in turn can negatively affect sexual desire160,161,162. For example, patients with gastrointestinal diseases might have an ostomy or stoma as a result of disease and/or treatment163,164,165,166. The presence of a stoma might influence patient self-perception and inhibit RAI by diminishing the desire for sexual intercourse and intimacy160,161. Reported concerns include anxiety about faecal leakage during intercourse, embarrassment about odour and concern about perception of the stoma by a sexual partner167,168. Among patients with a stoma (n = 540), 51% lived with their stoma for approximately 1–5 years and many described the stoma as negatively influencing their body confidence and sexual desire167. Additionally, in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC; n = 141), compared with patients with no history of an ostomy (n = 98) and patients with a history of a temporary ostomy (n = 18), those with a permanent ostomy (n = 25) have markedly worse body image, even when adjusting for age, sex and depressive symptoms (P < 0.001)168.

Non-malignant gastrointestinal diseases

Non-malignant diseases of the colon, rectum and anus include structural diseases, DGBI, infectious diseases, and inflammatory diseases. It is important for health-care professionals to recognize how each of these disorders and their treatments might affect pleasurable RAI to counsel patients, identify the issue (Fig. 4) and select appropriate management (Table 1).

Structural gastrointestinal diseases

Structural gastrointestinal diseases are common globally169,170, with the exact prevalence and incidence likely being underreported171. Structural gastrointestinal diseases include diseases of the anus (external haemorrhoids, anal fissures, anorectal fistulas), rectum (internal haemorrhoids, rectal prolapse, perirectal abscess) and colon (colonic polyps, diverticular disease)172 (Table 1). Haemorrhoids and anal fissures are among the most common, affecting, for example, at least 13% of the adult population in the USA171.

Anodyspareunia and structural gastrointestinal disorders, such as anal fissures, are indeed strongly linked65. However, in patients who regularly engage in RAI, an anal fissure is likely not from a hypertonic sphincter and likely due to traumatic preparation (enemas, fingers to clean stool, overwiping) or intercourse (inadequate lubricant, aggressive partner)173,174. Before recommending treatment for anal fissures in patients engaging in RAI, a thorough history is necessary as topical calcium channel blockers or botulinum toxin might not be appropriate and conservative management, including increasing fibre, sitz baths and education, might be preferred174.

Before diagnosing idiopathic anodyspareunia, it is important to exclude pain originating from structural gastrointestinal disorders. Utilizing the term ‘genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder’ as a surrogate for anodyspareunia, a cross-sectional ecological study (published as a thesis) found that cisgender sexual minority men who met the study criteria for anodyspareunia (n = 175) were approximately three times more likely to report a history of anal fissures (37%) and 1.5–2 times more likely to report a history of haemorrhoids (48%) than patients who did not meet criteria175. In patients with recurrent anal fissures, chronic ischaemia can result in increased anal sphincter tone and increased anal resting pressure, further predisposing to anodyspareunia176.

Patients with structural gastrointestinal diseases might be predisposed to arousal dysfunction, orgasm dysfunction and/or decreased sexual desire. Haemorrhoids can affect arousal by shunting blood away from erectile tissues177. Pelvic and anal muscular contractions can inhibit venous return from the haemorrhoid plexus, further inhibiting functional blood circulation during RAI177,178. Diverticular diseases might be associated with erectile dysfunction through physical vessel blockage, inflammation and vasculopathies preventing blood flow to erectile tissues152,153. Structural disorders can also influence sexual desire through changes to the physical appearance of the anus, which might result in self-consciousness and decreased desire to engage in RAI179,180.

Disorders of gut–brain interaction

DGBI affecting the colon, rectum and anus include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), chronic constipation, functional diarrhoea, faecal incontinence, dyssynergic defecation, and functional abdominal bloating and distension, among others172. Similar to structural diseases, prompt recognition of their effects on RAI and appropriate treatment is crucial (Table 1).

Sexual dysfunction in patients with IBS is common, with decreased desire as the most frequently reported manifestation181, occurring in ~21% of participants with IBS (n = 283) in one study182. Decreased sexual desire in IBS is multifactorial, including both physiological and neurotransmitter alterations. Approximately 95% of serotonin is produced in the gastrointestinal tract, which, when dysregulated, can contribute to gut distension, motility and visceral hypersensitivity183,184,185. Patients with IBS have decreased expression of the serotonin reuptake transporter184, which is responsible for regulating serotonin levels184. An increase in serotonin can lead to diarrhoea, discomfort and decreased sexual desire183,184. Patients with IBS are three times more likely to have anxiety or depression than patients without IBS, with an estimated global prevalence of up to 23%186,187. Medications for anxiety and depression, referred to as central neuromodulators in DGBI, can cause adverse effects that include issues with arousal, orgasm and desire188. Before initiating patients on these medications, it is important to assess baseline sexual function to distinguish between subsequent disease effects and medication-related problematic RAI4.

A history of trauma, including sexual abuse, has long been considered a risk factor for patients with IBS and DGBI189,190. Although trauma prevalence varies based on contextual factors, cisgender heterosexual women and people from sexual and gender minority communities are vulnerable to trauma191. Intimate partner violence, which includes physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse perpetuated by a current or former partner or spouse192,193, is another important consideration when diagnosing problematic RAI for a patient with DGBI194. Intimate partner violence is more common among cisgender heterosexual women and people from sexual and gender minority communities192,193. People from sexual and gender minority communities face unique barriers to obtaining support for intimate partner violence, including stigma and structural inequities195. In the context of RAI, intimate partner violence might include a partner refusing to use or secretly removing a condom during intercourse and/or intentionally infecting a victim with an STI (such as HIV) as a means to gain control and power192,193.

A person presenting with problematic RAI with a history of intimate partner violence might complain about DGBI due to anxiety194, anodyspareunia due to a hypertonic anal sphincter139,146,147,148,149, or an anal tear or fissure196. It is important to screen for intimate partner violence in patients presenting for problematic RAI196; screening can include a psychological assessment176, a comprehensive physical exam looking for bruises, bites, cuts, burns or broken bones at various stages of healing (especially in the extremities)196, and an anal exam to look for fissures, tears or bruises and assess sphincter tone139,146,147,148,149. Thus, when discussing and diagnosing problematic RAI, it is important to consider a history of trauma, as trauma is a risk factor for painful RAI197 and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction190,198.

Infections of the colon, rectum and anus

Infectious diseases affecting the colon, rectum and anus that can lead to problematic RAI include condyloma acuminata (from HPV), HIV or AIDS, folliculitis, infectious proctitis, hepatitis, protozoal infections, and enteropathogenic bacterial infections (Table 1).

HPV, which is transmitted through skin–skin contact (including anal–penile and anal–oral RAI), is the most common STI worldwide with an estimated prevalence of 44%199. Condylomata acuminata (anogenital warts) arise in approximately 1% of the global population200,201,202; however, they are twice as common in sexual minority men and can substantially decrease the desire to engage in RAI, whether painful or painless203. Similarly, in cisgender women, anal warts have substantial negative psychosexual effects and can affect desire162. Treatment for condylomata can help alleviate cosmetic concerns; however, local treatments can result in pain during RAI200,201. Condylomata can extend into the intra-anal canal200,201, rich in innervation. As such, treatments for condylomata, including topical and ablative therapies, are frequently associated with pain204,205 and anodyspareunia150. Thus, patients with condylomata should be counselled on the possible risk of treatment-related anodyspareunia.

Patients can acquire and transmit bacterial STIs, including chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis, through RAI206, which can lead to problematic intercourse. If bacterial STIs are untreated, they can cause infectious proctitis207,208, which might be a risk factor for painful RAI, including anodyspareunia209. As STIs of the anorectum (and throat) are more likely to be asymptomatic than those of the genitalia210, it is particularly important to screen patients engaging in RAI for the appropriate STIs. Best practices for STI screening include urinary, oropharyngeal and anorectal swabs (Fig. 3).

It is well established that people living with HIV have an increased risk of sexual dysfunction, and HIV and antiviral therapies can negatively influence RAI by affecting desire and arousal211. Additionally, among cisgender sexual minority men, RAI is the primary route of HIV transmission212. In people living with HIV, issues with desire are likely multifactorial due to diarrhoea (antiretroviral-related opportunistic infections)213, body image changes (antiretroviral-induced lipodystrophy)211 and anxiety (fear of transmission)140,211,214. Anodyspareunia can also affect people living with HIV, reported in up to 18% of cisgender gay and bisexual men living with HIV in one study215. However, HIV itself might not be a risk factor for anodyspareunia as one study found no association between the two150. Yet, a different survey study of sexual minority men found that HIV status was associated with painful intercourse, although no distinction was made regarding the type of pain (anodyspareunia or dysorgasmia)209.

Viral hepatitis can be spread through RAI and could contribute to problematic RAI because damage to the liver and resultant hypoalbuminaemia might decrease sexual desire. The liver regulates albumin production, which is directly correlated to testosterone levels, whereby hypoalbuminaemia from a damaged liver can cause low testosterone, decreased sexual desire216,217 and problematic RAI. Additionally, hepatitis A virus and hepatitis E virus can be transmitted through RAI with a mouth or tongue (oral–anal intercourse) and hepatitis B and D viruses can be transmitted during RAI through bodily fluids218. Hepatitis C virus might be transmitted during RAI if there is active bleeding218.

Additionally, antiretroviral therapy, classically protease inhibitors used for the management of HIV and viral hepatitis, can cause erectile dysfunction211. However, due to inhibiting CYP3A4, protease inhibitors can increase the levels of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor concentrations; thus, for patients on protease inhibitors with arousal dysfunction, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors should be prescribed at a lower dose and uptitrated219,220,221.

For patients who engage in RAI, protozoal and enteropathogenic bacterial infections can provoke altered bowel habits222, making RAI painful, embarrassing and challenging overall. Engaging in RAI might pose a risk (potentially minor) of transmitting protozoal infections (such as Giardia intestinalis) and enteropathogenic bacterial infections (such as Escherichia coli) through oral–anal contact or through a contaminated object, such as a dildo, as the protozoa and bacteria can be located within microscopic faecal matter222. A case–control study in the USA (case n = 199; control n = 381) identified that, among several risk factors for giardiasis, “male–male sexual behaviour” was among the biggest risk factors for contracting Giardia whereas “female–female sexual behaviour” was not223; however, male–male sexual behaviour does not equate to oral–anal intercourse224. Although oral–anal intercourse might be a potential risk factor for certain infections, it might not be the biggest risk factor.

When evaluating risk factors, it is crucial to be aware of the social determinants of health. For example, in the case of Giardia, access to safe drinking water and sanitation is an important consideration225. Individuals from sexual and gender minority communities encounter unique barriers to accessing safe drinking water and sanitation226, including segregated sanitation facilities based on sex recorded at birth227, histories of trauma or bullying related to bathrooms and locker rooms228, as well as actual or perceived risk of violence in sanitation facilities at shared spaces226. Social determinants of health can substantially contribute to the overall profile for the risk of acquiring an infection, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive understanding beyond assuming that specific sexual behaviours solely contribute to an infection. In addition to advising patients on thoroughly cleansing the anus before anal–oral intercourse, discussing potential use of dental dams during anal–oral intercourse, cleaning sex objects (for example, dildo) after use in an anus, and washing hands after anal stimulation229, it is critical to ask about their ability to access clean water.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Nearly 6.8 million people worldwide live with IBD230, a chronic immune-inflammatory disorder encompassing Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis231. Crohn’s disease can affect anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract, including the perianal region in the form of skin tags, fissures, fistulas and strictures232. In ulcerative colitis, inflammation begins in the rectum and extends proximally through the colon in a continuous manner232. Malnutrition and extraintestinal manifestations, including inflammatory disorders of joints, skin and eye, also contribute to the effects of IBD on the quality of life of individuals45,231,232,233,234.

IBD incidence is rising, and it is estimated that it will affect 1% of the global population within the next decade235. IBD symptom onset typically occurs at 15–30 years of age236, with approximately 50% of patients with IBD diagnosed before the age of 35 years45. The prevalence of IBD among older patients (≥60 years old) is increasing rapidly due to a combination of new diagnoses among older adults and an ageing IBD population237. Given the growing incidence and population affected by IBD, understanding the effects of this disease on sexual health is essential45.

Both the disease and its treatments can affect sexual function, including RAI. Sexual dysfunction affects up to 40% of cisgender men and 97% of cisgender women with IBD45. However, there remains a paucity of data to support people with IBD who engage in RAI238. A mixed methods study (n = 50) of cisgender sexual minority men and women with IBD found that these patients experienced fear of judgement related to disclosing their sexuality and sexual practices238. The study highlighted that patients felt ‘robbed’ of their choice to engage in RAI as their gastroenterologists did not discuss RAI nor the effects of IBD and treatments on RAI238. The urgent need to address health inequities in people from sexual and gender minority communities with IBD was additionally identified in a cross-sectional analysis (n = 93) illustrating that individuals from sexual and gender minority communities with IBD have a high risk of mental health comorbidities, social exclusion and unmet nutritional needs239, which can contribute to problematic RAI.

Problematic RAI due to local inflammation

In the anorectal region, IBD can manifest as skin tags, fissures, proctitis, strictures and inflammatory skin disorders; whereas perianal fistulas occur primarily in Crohn’s disease (17–21%240 of patients developing a perianal fistula at 10 years, with incidence increasing with disease duration), they also occur in ~4.5%241 of patients with ulcerative colitis after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA)240,242. Perianal disease can be disfiguring and greatly affects quality of life243.

Pain from inflammation and flares might interfere with pleasurable RAI in people with IBD. Proctitis (inflammation of the rectum) is a common manifestation of IBD, occurring in up to 40% of patients with IBD244,245,246, and is associated with rectal pain, tenesmus and bleeding232. For a patient with IBD engaging in RAI, increased bleeding from proctitis might not be life-threating, but could create anxiety for the patient (and partner if present) from concern as well as confusion regarding the underlying aetiology of the bleeding. Additionally, in individuals with prostates affected by IBD with rectal involvement, local inflammation can cause persistent prostatic inflammation217, likely affecting RAI4.

Crohn’s disease-associated perianal fistulas, which are tunnels that occur between the rectum or anal canal and perianal skin, might also contribute to problematic RAI. These lesions are challenging to manage and can be chronic and painful240. The relative position of the fistula (intersphincteric, transphincteric, suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric) might influence sphincter function, treatment type240 and resultant sphincter tonicity247, and therefore RAI.

Perianal fistulas might damage other surrounding structures involved in pleasurable RAI, cause scarring that might make the area feel dry or tight or cause pain during penetration, especially if the fistula is filled with fluid167. Perianal fistulas are also frequently associated with anorectal strictures causing anorectal narrowing248,249, which could limit the ability to engage in RAI, potentially even making penetrative RAI impossible. Additionally, rectovaginal and colo-urethral fistulas can lead to unintentional leakage, causing anxiety surrounding RAI167.

Perianal skin tags are generally benign and can be found in healthy individuals; however, they are more commonly associated with Crohn’s disease250. When enlarged, skin tags can cause idiopathic pain and anatomical blockage251,252,253. Other skin manifestations from inflammation in patients with IBD include erythema nodosum, pyoderma granulosum, anogenital cutaneous Crohn’s disease, and general impaired skin or wound healing243,254, all of which can contribute to pain255,256 and likely anodyspareunia. Although more research is needed, patients with IBD might consider avoiding RAI if pain occurs during penetration and/or if there is active flaring208,257,258,259.

Problematic RAI due to systemic inflammation

Systemic inflammation in patients with IBD can cause fatigue, increased faecal urgency, faecal incontinence, bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pain and malnutrition232,233,236,260, all of which could be associated with problematic RAI. In IBD, fatigue is a common symptom present in up to 50% of patients at diagnosis45. Fatigue can be extremely distressing for patients with IBD and one of the primary contributors to sexual dysfunction261. Patients also report abdominal pain, diarrhoea and the fear of having diarrhoea as contributing to issues with intimacy261.

Problematic RAI due to systemic therapies

Systemic treatments for IBD can influence sexual function45, and likely RAI. Studies investigating the association of steroid use and sexual function in patients with IBD found that prolonged steroid use is associated with decreased sexual satisfaction and pleasure. Prolonged steroid use can lead to adrenal insufficiency, a known risk factor for fatigue and decreased desire262, and body image disturbances, due to acne, fluid retention, obesity, stretch marks and hirsutism45. Patients with IBD identify corticosteroid-related body changes to be most contributory to body image disturbances45,263. Body image dissatisfaction is associated with arousal and orgasm dysfunctions264,265 and, notably, body image might be particularly important for sexual minority men265. Health-care providers should limit the length of steroid use to prevent adverse effects of body image disturbances on sexual health264,265. Biologic therapies to control active inflammation might reduce the need for steroids and the associated adverse effects, helping to prevent steroid-related problematic RAI.

Problematic RAI due to surgical treatments

For people with IBD engaging in RAI who require surgical intervention, a comprehensive discussion on surgical treatment options for IBD and associated risks is essential and should potentially involve their sexual partners (Fig. 5). Rectal inflammation itself can affect RAI but surgical treatments, including bowel resection, fistula repair, diversion procedures and completion proctectomy, can cause complications that further influence RAI such as bleeding, mucus discharge and tenesmus.

a, Effect of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) resection procedures on receptive anal intercourse (RAI). Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis surgery is a gold standard for refractory ulcerative colitis; however, it might affect ability to engage in RAI. The J-pouch, created from ileum and anastomosed to the anus267, might cause problematic RAI if it becomes inflamed (pouchitis) or if it is too small to accommodate an object for RAI. For patients with Crohn’s disease who require colectomy, ileorectal anastomosis208 might be another option, which is associated with fewer bowel movements and night leakages, but increased faecal urgency than ileal pouch–anal anastomosis269. Total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy is reserved for specific cases240, with implications for people who engage in RAI. Patients with IBD might also undergo temporary or permanent ostomy163, which can affect body image, intimacy and intercourse160,161. b, Effect of IBD fistula procedures on RAI. Patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease often require abscess drainage and seton placement240. Traditional setons can be uncomfortable and affect sexual intimacy167; knotless setons are associated with less pain272, potentially enabling more pleasurable RAI. Fistulotomy can be considered for low intersphincteric fistulas240; however, this approach might create a scar, affecting anorectal elasticity and RAI. Sphincter weakening and stenosis240, which can lead to decreased arousal or anodyspareunia, respectively, are other possible complications from sphincterotomy. In eligible patients, mucosal advancement flap and fistula ligation might be good options to preserve sphincter function and pleasurable RAI.

Intestinal resection and colectomy rates, though slightly declining since the availability of biologic therapies, persist with 7–10% of patients with IBD undergoing one of these procedures266. Restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA, involving the creation of a pouch (called J-pouch) from tissue from the ileum and anastomosis to the anus267, is the gold standard for patients with refractory ulcerative colitis and patients with specific conditions (such as familial adenomatous polyposis).

Qualitative interviews with individuals with IBD from sexual and gender communities reveal how IPAA surgery adversely affected their ability to engage in RAI238. Patients expressed feeling uninformed238 and noted that, while there was guidance on sexual health after surgery, RAI was completely omitted, further affecting their mental health, sexual health and overall quality of life238. Discussing the length of the pouch and pouchitis (inflammation of the J-pouch)267 with people who engage in RAI is likely important — pouch length might affect the ability to accommodate different lengths of objects inserted during RAI259 and pouchitis might make RAI painful.

For patients with Crohn’s disease requiring colectomy, ileorectal anastomosis, which preserves the rectum208, is associated with better sexual function in general, improved fecundity, fewer bowel movements, and fewer night bowel leakages compared with an IPAA268, although it is associated with increased faecal urgency269. It has been reported that hand-sewn anastomosis might be preferred over stapled anastomosis for people engaging in RAI to allow for continued intercourse270. Notably, ileorectal anastomosis is infrequently used in patients with ulcerative colitis due to the potential of persistent rectal inflammation and risk of colitis-associated malignancy268,271.

Patients with IBD might also undergo temporary or permanent ostomy, with up to 10% of patients with Crohn’s disease living with a permanent stoma163, which can affect body image, intimacy and intercourse160,161. Although reserved for select patients, it is important to be aware that total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy, which removes the entire colon and rectum without re-establishment of continuity of the gastrointestinal tract, results in permanent ostomy and would permanently prohibit RAI240, which could substantially and negatively influence quality of life and identity for people who engage in RAI.

In patients with perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease, fistula management often involves surgical procedures. The most common are abscess drainage and seton placement240. Setons in situ can cause pain and discomfort272 as well as frustration due to decreased sexual spontaneity and difficulties explaining setons to sexual partners167. Knotless setons are associated with significantly less pain (P < 0.001; n = 60)272, possibly enabling more pleasurable RAI. Fistulotomy, typically used for low intersphincteric fistulas that have failed medical management240, carries many risks including scar formation240 (which could reduce anorectal elasticity and the ability to accommodate an object for RAI) and sphincter weakening240 (which could cause decreased arousal). For patients who engage in RAI and are candidates, mucosal advancement flaps and fistula ligation might be preferred options. Mucosal advancement flaps involve mobilizing rectal tissue to cover fistula tracts and preserve the sphincters240; however, the procedure can only be performed in patients without active proctitis and reoperation occurs in up to 50% of patients214. Ligation of intersphincteric fistulas, which has a low risk of faecal incontinence, is another treatment option that might preserve sphincter function240.

Colon, rectal and anal cancer

Maintaining the capacity for sexual pleasure, including pleasurable RAI, after cancer diagnosis and treatment can be fundamental to the quality of life of cancer survivors. Patients with colon, rectal or anal cancer have estimated 5-year overall survivals of 63%, 68% and 70%, respectively273, and advancements in multimodality cancer therapies continue to increase the number of CRC and anal cancer survivors living with treatment-related toxicities44,274,275,276. Among colon, rectal or anal cancer survivors, sexual dysfunction is frequent and distressing, respectively reported at rates of 47% and 28%49, 86% and 72%44, and 40% and 38%50 among male and female survivors.

Colorectal cancer

CRC is the third most common cancer worldwide277. The incidence of CRC can be influenced by oestrogen, an important consideration when managing female, transgender and gender diverse, and intersex patients278,279,280,281,282.

Survivors of CRC might experience iatrogenic sexual dysfunction, including problematic RAI. Approximately 80% of patients with colon cancer undergo surgery283 and patients with rectal cancer are treated with multimodality therapy, including combinations of systemic therapy, radiotherapy and surgery, depending on disease extent and biomarkers284. The probability of a permanent ostomy for patients with CRC who undergo surgery ranges from 10% to 30%164, with up to 21% of patients with rectal cancer who undergo surgery requiring a permanent stoma165. In a survey study of 418 survivors of CRC of varied sexual orientations, 70% of patients reported issues with sexual desire285. When stratified by sexual orientation, a markedly higher proportion of sexual minority patients expressed body image dissatisfaction than heterosexual patients (12% versus 6%; P = 0.04) and a significant association between health-care utilization and sore buttock skin was observed in sexual minority patients but not in heterosexual patients285. Sore buttock skin and body image dissatisfaction can contribute to problematic RAI, highlighting the importance of counselling patients with CRC on these possibilities.

Survivors of CRC experiencing problematic RAI after treatment can encounter inadequate support and feelings of isolation286, which might worsen any treatment-related pain they could be experiencing287. In general, individuals from sexual and gender minority communities experience more loneliness and less familial and social support than the general population288,289,290,291,292. Additionally, they are more prone to experiencing pain during cancer survivorship than their cisgender heterosexual counterparts287. Loneliness triggers similar brain signalling and inflammatory responses as physical pain, and the isolation experienced by individuals from sexual and gender minority communities likely contributes to the observed pain disparity287.

Neglecting conversations about RAI in clinical settings might inadvertently contribute to problematic RAI286 as the omission of RAI-related discussions during cancer care could amplify feelings of isolation, ultimately worsening pain287 and sexual dysfunction. A qualitative analysis (published as a thesis) of semi-structured interviews with six sexual minority men with cancer revealed that the two patients with CRC experienced concerns related to problematic RAI, including pain and relationship breakdowns. However, unlike the three sexual minority men with prostate cancer, the CRC survivors struggled to identify support groups, resulting in more feelings of isolation and loneliness286.

Recognizing sexual health as a crucial component in cancer survivorship, it is essential for clinicians to discuss RAI during CRC care because, by addressing RAI during care and fostering a sense of belonging, clinicians could potentially help mitigate problematic RAI and improve the quality of life for survivors of CRC who engage in RAI.

Anal cancer

Approximately 90% of new anal cancer cases are caused by HPV, often transmitted through sexual intercourse, including RAI293. Despite global efforts in HPV vaccination294,295 and improved anal dysplasia screening296, new anal cancer cases continue to rise worldwide297.

Among the general population, anal cancer is rare; however, among sexual minority men, transgender and gender diverse people, and those with long-term immunosuppression, anal cancer is a relatively common malignancy206,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305. In the USA, sexual minority men constitute approximately 43% of new anal cancer cases among cisgender men306, with incidence rates ~20–80 times higher in cisgender sexual minority men than in cisgender men and/or women55. Additionally, among gender-expansive individuals, anal cancer ranks as the second most common cancer301.

Sexual minority men with anal cancer are more likely to be single than cisgender heterosexual patients. Mauro et al. found that 60% of sexual minority men with anal cancer were single307, consistent with other studies suggesting that people from sexual and gender minority communities with cancer are more likely to be single than cisgender heterosexual people with cancer287,308, assumed to be proportional to societal tolerance and legal acceptance of same-sex relationships309.

Anal cancer and its treatments can lead to sequelae affecting sexual pleasure4,42,44. In patients with anal cancer, 80% present with locoregional disease310 and are treated with sphincter-sparing concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy310. Approximately 10% of patients with anal cancer311 receive an ostomy prior to chemoradiation treatment and, of those patients, at least half go on to live with a permanent ostomy166. Treatment of anal cancer with chemoradiation spares patients the morbidity associated with abdominoperineal resection310; however, it can still adversely affect sexual function312,313,314. For example, in a prospective study evaluating the effects of chemoradiation on quality of life in sexual minority men with anal cancer (mean age: 59.3 years)307, Mauro et al. showed that quality of life and sexual function (specifically penile erectile function) worsened during treatment. Both returned to baseline within a year following treatment completion. However, there were no questionnaires related to the effect of treatment on RAI specifically. To date, no published studies have systematically examined the effect of anal cancer treatments on RAI, and studies are needed to fully elucidate the effect of treatment on RAI.

Surgery and RAI

Surgical resection in patients with CRC can lead to problematic RAI through damage to the neurovasculature and organs responsible for arousal and orgasm4 (Fig. 6). Surgical approaches can also include colostomy, which can affect body image and desire160,161. Nerves implicated in pleasurable RAI can become damaged from surgery, thermal injury, inflammation, ischaemia or stretching315. Patients with colon cancer are treated with a colectomy, which can damage the inferior mesenteric nerves and hypogastric nerves, both of which facilitate sexual, urinary and gastrointestinal function315. Depending on the location of the rectal tumour (low, middle or high), surgical techniques might damage the genitopelvic neurovasculature or even completely remove functional anatomy (including the sphincters)316. For low and middle rectal tumours, sphincter-sparing low anterior resection (LAR) with or without a coloanal anastomosis or abdominoperineal resection with total mesorectal excision might be used, whereas high rectal tumours can undergo a LAR with a higher anastomosis, thus sparing the morbidity associated with extensive resection316.

a, Surgery-related problematic receptive anal intercourse (RAI). Sphincter-sparing surgery is associated with less morbidity than an abdominal perineal resection461. An abdominal perineal resection removes the sphincters and anus, precluding RAI461,462. A low anterior resection with nerve-sparing techniques can be used to reduce sexual dysfunctions, including problematic RAI; however, it can still damage the hypogastric nerves and neurovascular bundle462, adversely affecting arousal463. Ongoing debate exists on removal of the rectoprostatic or rectovaginal fascia for posterior rectal tumours but it is removed during total mesorectal excision for anterior rectal tumours462,464. The rectoprostatic fascia is the location of a neovagina in transfeminine people, and removal of this space would complicate future reconstructive surgery331. Additionally, for anterior tumours, total mesorectal excision has an increased risk of damaging the neurovascular bundle responsible for erectile tissue engorgement during RAI arousal462. Damage to these nerves might also result in low anterior resection syndrome, characterized by increased frequency of bowel movements, tenesmus and faecal incontinence315. The probability of a permanent ostomy for a patient with colorectal cancer undergoing surgery ranges from 10% to 30%164, with potentially 21% of patients with rectal cancer who undergo surgery requiring a permanent stoma165, decreasing sexual desire160,161 and affecting RAI. b, Radiation-related problematic RAI. Radiation contributes to problematic RAI in patients with anal and rectal cancer through long-term anal pain, perianal discomfort, rectal bleeding and faecal incontinence4,42,44,310,313,314. Radiation can damage the functional anatomy involved in pleasurable RAI due to normal functional tissue cell death, inflammation, mucosal ulceration and fibrosis319. Approximately 10% of patients with anal cancer311 receive an ostomy prior to chemoradiation treatment and, of those patients, at least half go on to live with a permanent ostomy, affecting patient self-perception and the desire for sexual intercourse and intimacy166. c, Systemic treatment-related problematic RAI. Systemic therapy, including chemotherapy335,336 and immunotherapy, can influence pleasurable RAI through skin changes, diarrhoea4,150 and resultant malabsorption338, colitis346, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity340. Immunotherapy is emerging as part of the treatment for colorectal and anal cancers333,344,345. Immunotherapies are associated with diarrhoea and/or colitis307, which might cause anodyspareunia or adrenal insufficiency347, leading to decreased sexual desire and body image dissatisfaction, and may even be associated with vitiligo, which could affect sexual desire465.

Patients with rectal cancer who undergo surgery are likely at increased risk of problematic RAI compared with patients with colon cancer who undergo surgery. A multicentre cross-sectional analysis of survivors of colon cancer (n = 1,145) and rectal cancer (n = 350) showed that LAR syndrome — characterized by increased frequency of bowel movements, tenesmus and faecal incontinence — occurred more frequently in patients with rectal cancer (55%) than in those with colon cancer (21%)317. Despite more survivors of rectal cancer having received neoadjuvant therapy (radiation and/or systemic therapy) than survivors of colon cancer (72% versus 1.7%; P < 0.001), neoadjuvant therapy was not a risk factor for LAR syndrome in this population. Risk factors for this syndrome included female sex and a prior diverting stoma. Additionally, patients who received adjuvant therapy and left hemicolectomy were at lower risk of developing LAR symptoms, further implicating disease location and direct surgical nerve damage as contributing factors317.

The role of non-operative management for rectal cancer is evolving. Patients with rectal cancer managed non-operatively with chemoradiation alone have a lower risk of LAR syndrome than those treated with multimodality therapy. In a cross-sectional survey study of survivors of rectal cancer, patients managed non-operatively with chemoradiation alone (n = 23) experienced fewer LAR syndrome symptoms and less distress than those treated with multimodality therapy (n = 101)318. Using multivariable linear regression, the authors found that surgery was the only statistically significant predictor of worse bowel dysfunction318. Rectal cancer treatments can damage functional anatomy and lead to problematic RAI, especially in patients with low rectal cancers for whom the sequelae can be similar to what is seen after treatment of anal cancer.

Radiation and RAI

Radiation therapy can lead to problematic RAI in patients with anal and rectal cancer through long-term anal pain, perianal discomfort, rectal bleeding and faecal incontinence4,42,44,310,313,314 (Fig. 6). Radiation can damage the functional anatomy involved in pleasurable RAI as a result of normal functional tissue cell death, inflammation, mucosal ulceration and fibrosis319. An observational cohort study of 79 survivors of anal cancer with late treatment toxicity identified that the radiation dose to the hottest 0.5 cm3 of functional anatomy — perianal skin, anal canal and large bowel — was associated with skin toxicity, anal toxicity (for example, sphincter dysfunction) and diarrhoea320.

Patients might experience anodyspareunia due to damage of the sensitive perianal skin and anal canal. Thematic analysis of qualitative interviews with survivors of anal cancer (n = 84) identified problematic RAI as a contributing factor to poor quality of life, for example, one sexual minority male patient discussed his inability to enjoy pleasurable RAI with his husband due to fear of anodyspareunia321. Similarly, prostate-directed radiation has been associated with anodyspareunia through incidental damage to the anus4,15. Given that the anal canal receives a higher dose of radiation during anorectal cancer treatments than prostate cancer treatments, it is important to acknowledge the risk of anodyspareunia when recommending or initiating anal cancer radiation treatments320,322,323.

Radiation can also cause issues with orgasm and arousal by damaging erectile tissue, prostate or paraurethral glands, anal sphincters and anal canal4,42,324. Radiation treatment for anal and rectal cancer includes the prostate as part of its clinical target volumes, which could lead to issues with arousal and orgasm during RAI325. Radiation therapy can damage the anal sphincters and anal canal, especially in patients with large tumours, causing inflammation and fibrosis326,327. Additionally, if the cancer invaded the anal sphincters, sphincter dysfunction can occur even after tumour regression due to initial damage from the tumour. In addition to faecal incontinence, sphincter dysfunction can result in a decreased ability to squeeze a phallus or object for sexual pleasure, further affecting arousal and orgasm in RAI328,329. Fibrosis of the anal canal might cause anal strictures and anal stenosis330, which could lead to painful RAI and anodyspareunia4.

Radiation for anorectal cancer might also influence cosmesis associated with genital-affirming surgery331, influencing the ability and desire of a patient to engage in RAI. For example, a transfeminine person who underwent radiotherapy for anal cancer developed lymphoedema due to the interaction between radiation and injected liquid silicone in the pelvis332. It is important to counsel people experiencing gender incongruence who underwent or are planning to undergo genital-affirming procedures on the implications of radiation treatment on cosmetic outcomes333,334. Moreover, silicone injection is not a standard genital-affirming surgical practice, and it is important for health-care professionals to ask appropriate questions and offer counselling while considering non-standard therapies.

Systemic therapy and RAI

Systemic therapy can negatively affect pleasurable RAI through skin toxicity, malabsorption from diarrhoea and neurotoxicity (Fig. 6). Mitomycin-C335 and 5-fluorouracil336 can cause skin ulceration, skin pain and skin irritation, and 5-fluorouracil can cause diarrhoea337. Diarrhoea can decrease sexual desire4 and cause anodyspareunia150. Malabsorption can lead to pelvic floor muscle weakening and cramps338, causing arousal and orgasm dysfunction155.

Systemic therapy can also affect arousal and orgasm339 through chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity340. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity is among the most common adverse effects, with a prevalence ranging from 19% to 85%, and can markedly affect pleasurable intercourse341. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity is dependent on agent and dose and particularly common among platinum-based antineoplastics (oxaliplatin and cisplatin), vinca alkaloids (vincristine and vinblastine), epothilones (ixabepilone), taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib) and immunomodulatory drugs (thalidomide)341. Cisplatin, oxaliplatin and other alkylating agents are commonly used for CRC treatment, and secondary nerve damage can result in arousal dysfunction and anorgasmia342. The underlying mechanism for nervous system damage by alkylating agents is neuroinflammation and altered neuron excitability341. Neuroinflammation is caused by the activation of immune cells and an increase in inflammatory cytokines341. These agents also create reactive oxygen species, leading to apoptosis and inflammation. Lastly, chemotherapy can alter the expression of ion channels, including upregulating sodium-gated channels and downregulating potassium-gated channels inducing neuronal hyperexcitability341,343, which might alter sensitivity and therefore influence arousal and orgasm341.

Immunotherapy is emerging as part of the treatment for CRC and anal cancer333,344,345. Immunotherapies are associated with colitis346 (which might cause anodyspareunia) and adrenal insufficiency347 (which is associated with decreased sexual desire and body image dissatisfaction) (Fig. 6). Systemic treatment-related effects can last for many years, and it is important to discuss the lasting effects of systemic therapy on sexual health with patients with CRC or anal cancer.

Treatment choice

Although anal and colon cancers are typically treated with chemoradiation and surgical resection, respectively, rectal cancer is treated with multimodality therapy. As treatment paradigms for cancer continue to evolve, select patients, particularly those with rectal cancer, might be faced with unique treatment choices with variable toxicity profiles348,349,350,351. To guide patients with rectal cancer, physicians should use knowledge of the sexual behaviours of patients, including their preferred role-in-sex (insertive partner (‘top’), receptive partner (‘bottom’), both (‘vers’), neither (‘side’)4) and anatomy. Systematic collection of patient-reported outcomes related to all sexual behaviours, including RAI, will be important to inform future treatment strategies and inform treatment choice decision-making and counselling351.

Management of problematic RAI

Strategies to manage, mitigate and treat problematic RAI can help patients prevent and/or restore the ability to experience pleasure, arousal, orgasm and satisfaction3 (Tables 2 and 3). Although limited evidence exists regarding restorative therapies for pleasurable RAI4 (Tables 2 and 3), it is important to discuss potential therapies for pleasurable RAI rehabilitation. Discussing, characterizing and diagnosing the nature of problematic RAI for a patient (Fig. 3) can help provide insight into optimal strategies to engage in pleasurable RAI safely and confidently.

Engaging in RAI

Generally, if there is no pain, it is safe for patients with non-malignant gastrointestinal disorders to engage in RAI56,172,182 (Table 1). The unpredictability of pain, faecal incontinence, flatulence and/or discomfort208 might cause anxiety and depression regarding RAI. Direct partner communication regarding disease-specific insecurities and symptoms might help alleviate apprehension92,352,353. If it is difficult to receive more rigid objects due to strictures and tightening, pleasurable RAI from the tongue of a partner or soft and small anal beads354 might be good options. However, patients should be counselled on adequate cleaning and preparation to promote partner safety and intimacy.

Practically, antidiarrhoeals, fibre supplements, lower residue diet to control regularity, avoiding spicy foods, timing meals, and defecation immediately prior to intercourse might help control symptoms and relieve mental distress208,355,356. Anti-flatulence medications and/or positioning in the left lateral decubitus position for 15 min in advance of RAI can help expel and prevent unwanted flatulence357,358.

Resumption of RAI