Abstract

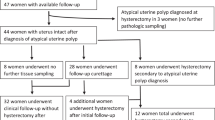

Tubal metaplasia of the endometrium may occasionally display cytologic atypia (atypical tubal metaplasia) resembling serous carcinoma or endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma. Although atypical tubal metaplasia is presumed to be reactive or degenerative in etiology, its clinical significance is unknown. In this study, we investigated atypical tubal metaplasia in regard to its immunoexpression of p53, Ki-67, and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), and its long-term clinical outcome. A total of 63 cases of atypical tubal metaplasia and 200 cases of endometrial samples with typical tubal metaplasia were followed for a mean of 64 and 61 months, respectively. Of the 63 atypical tubal metaplasia cases, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections from 16 cases were immunostained with antibodies to p53, Ki-67, and TERT. Sections from 13 cases of uterine serous carcinoma were also stained for TERT as control. After long-term follow-up, 5% of patients in the atypical tubal metaplasia group developed hyperplasia without atypia compared with 4% of patients in the control group (P=0.44), whereas 3% in the atypical tubal metaplasia group developed atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma compared with 2% in the control group (P=0.44). p53 immunoreactivity was either focal and weak or negative in all cases of both atypical and typical tubal metaplasia (P>0.05). Ki-67 immunoreactivity was present in 0–5% of cells in 94% of both atypical and typical tubal metaplasia (P>0.05). TERT immunoexpression was absent in all 16 cases of atypical tubal metaplasia, but present in all 13 cases of uterine serous carcinoma (P<0.0001). Our study indicates that atypical tubal metaplasia displays an immunostaining pattern similar to otherwise typical tubal metaplasia of the endometrium, and distinct from uterine serous neoplasms. The presence of atypical tubal metaplasia in endometrial samplings does not increase the risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia or malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Tubal (or ciliated cell) metaplasia of the endometrium is a frequent finding in endometrial sampling specimens and is commonly associated with the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and with anovulatory cycles.1 Characterized by ciliated columnar cells with bland round nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm, similar to the cells normally seen lining the fallopian tube, it is usually easily recognized. Occasionally, tubal metaplasia with cytologic atypia (atypical tubal metaplasia) is encountered in non-neoplastic endometrial biopsy or curettage specimens. This cytologic atypia is most likely reactive or degenerative in nature; however, it does raise the possibility of a poorly sampled invasive uterine serous carcinoma or endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma. Uterine serous carcinoma and serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma are both characterized by highly atypical nuclei with macronucleoli, although the latter is by definition entirely non-invasive.2 The identification of invasive or intraepithelial serous carcinoma in endometrial samplings is often associated with early extrauterine disease3, 4 and therefore warrants hysterectomy and surgical staging procedures. On the other hand, the clinical significance of atypical tubal metaplasia is unknown. Previous studies have shown significant overexpression of p53, Ki-67, and human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) in invasive and non-invasive uterine serous carcinoma.5, 6, 7, 8 The current study evaluates the expression of p53, Ki-67, and TERT in atypical tubal metaplasia, and the usage of these immunohistochemical markers in differentiating this metaplasia from intraepithelial or invasive uterine serous carcinoma. This study also uses long-term follow-up to evaluate the risk of subsequent endometrial neoplasia associated with atypical tubal metaplasia.

Materials and methods

The archives of the department of pathology at Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, were searched from January 2001 through August 2008. A total of 63 cases of benign endometrial biopsies or curettages with histologically demonstrable atypical tubal metaplasia were identified and reviewed. The specimens were all from patients with dysfunctional uterine bleeding and include 30 poorly active endometrium, 16 atrophic endometrium, 2 weakly proliferative endometrium, 3 disordered proliferative endometrium, 8 disintegrating endometrium, and 4 endometrial polyp cases. Endometrial hyperplasia or malignancy was not identified in any of these study cases. The criteria for cytologic atypia of atypical tubal metaplasia included enlarged pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei, small to prominent nucleoli, and increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1). The mean age of patients with atypical tubal metaplasia was 56 years. Follow-up information was available in all cases. As controls, 200 cases of benign endometrium from patients with dysfunctional uterine bleeding were selected from the first 2 months of 2001. Each control case had tubal metaplasia without cytologic atypia. The mean age of the control group was 54 years. Unpaired Student t-test was used to compare the age and follow-up period for the two groups; Fisher Exact Test was used to compare outcome.

(a) Tubal metaplasia with bland uniform nuclei (40 × ). (b, c) Tubal metaplasia with mild atypia seen as slight variation in nuclear size, hyperchromatism, and presence of small nucleoli (40 × ). (d–f) Atypical tubal metaplasia displaying marked nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromatic smudgy nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (d, f—40 × ; e—20 × ).

Of the 63 cases of atypical tubal metaplasia, 16 cases were arbitrarily selected for further immunohistochemical evaluation with antibodies to p53 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), Ki-67 (Dako), and TERT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Immunohistochemistry was carried out manually using protocols optimized and validated under the conditions of our laboratory. From each case, 5 μm sections were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, then deparaffinized and rehydrated. Immunohistochemistry for p53 (1:50 dilution), Ki-67 (ready-to-use antibody), and TERT (1:40 dilution) was carried out with antigen retrieval using a water bath in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and detection via the avidin-biotin peroxidase method of the DAKO LSAB2 system. Protein expression was visualized with diaminobenzidine, and sections were then counterstained and mounted. Positive p53 and Ki-67 results were indicated by brown staining of the nucleus. For TERT, brown distinct cytoplasmic and/or nuclear staining was considered positive. Appropriate positive and negative controls were run simultaneously with each batch of slides.

The immunohistochemical staining pattern of p53 and Ki-67 in the selected 16 atypical tubal metaplasia cases was compared with typical tubal metaplasia identified in other regions of the same 16 slides. TERT immunoreactivity in the selected 16 atypical tubal metaplasia cases was compared with immunoreactivity in 13 cases of uterine serous carcinoma, which were also retrieved from our department's archives and stained for TERT as described above. Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare staining characteristics of the two groups.

Results

The clinical characteristics and outcomes of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. The patients in the atypical tubal metaplasia group (n=63) were followed for a mean of 64 months. Follow-up revealed three cases of simple hyperplasia, one case of complex atypical hyperplasia, and one case of moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The lone carcinoma case was diagnosed 88 months after the initial biopsy showing atypical tubal metaplasia. The patients in the control group were followed for a mean of 61 months, which revealed seven cases of hyperplasia without atypia (four simple hyperplasia, three complex hyperplasia), one simple atypical hyperplasia, and three complex atypical hyperplasia.

Long-term follow-up revealed hyperplasia without atypia in 3 of 63 cases (5%) in the atypical tubal metaplasia group, and 7 of 200 cases (4%) in the control group (P=0.44). Atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma was present in 2 of 63 (3%) atypical tubal metaplasia cases and in 4 of 200 (2%) control cases (P=0.44). There was no significant difference in the incidence of hyperplasia without atypia or atypical hyperplasia/carcinoma between the two groups.

p53

The atypical tubal metaplasia cells were negative for p53 in 4 of 16 cases (25%) and showed focal, weak p53 immunoreactivity (Figure 2) in 12 of 16 cases (75%). Typical tubal metaplasia was negative for p53 in 3 of 16 cases (19%) and showed focal, weak positivity in 13 of 16 cases (81%). There was no significant difference in the staining patterns of p53 between atypical and typical tubal metaplasia (P>0.05). These results are summarized in Table 2.

Ki-67

Of the 16 selected atypical tubal metaplasia cases, eight (50%) were completely negative for Ki-67 immunostain. In seven cases (43%), less than 5% of the atypical cells were positive for Ki-67 (Figure 2). One case (6%) exhibited immunoreactivity in ∼25% of the atypical cells. In the regions of typical tubal metaplasia, six cases (37.5%) were completely negative, nine cases (56.2%) showed less than 5% positivity, and one case (6.3%) showed greater than 5% positivity for Ki-67. As shown in Table 2, there seemed to be no significant difference in Ki-67 staining between atypical and typical tubal metaplasia (P>0.05).

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)

The atypical tubal metaplasia cells were completely negative for TERT (Figure 3) in the 16 selected cases (0/16). Of the 13 cases of uterine serous carcinoma, six (46%) showed diffuse strong immunoreactivity with TERT (Figure 3) and three (23%) exhibited moderate TERT immunoreactivity. Only four cases (31%) showed focal, weak immunostaining, and no cases were completely negative for TERT. These results, as summarized in Table 3, indicate a significant difference in TERT staining between atypical tubal metaplasia and uterine serous carcinoma (P<0.0001).

Discussion

When endometrial samplings display tubal metaplasia exhibiting cytologic atypia, including nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia, prominent nucleoli, and increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, the possibility of an incompletely sampled uterine malignancy is raised. The features of atypical tubal metaplasia may histologically resemble some cytologic features seen in uterine serous carcinoma and serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma. This study evaluated the immunoprofile of atypical tubal metaplasia and the long-term outcomes in these patients.

p53

The p53 tumor suppressor gene is one of the most commonly altered genes in human malignancies, and is mutated in approximately half of most cancer types arising in a wide variety of tissues.9 When cells lack normal functional p53 protein, inactive mutant p53 protein can accumulate in the nucleus, leading to a relative overexpression, which is detectable by immunohistochemistry.10 Uterine serous carcinoma characteristically exhibits diffuse strong nuclear positivity with p53,11 a finding also seen in serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma.12 In contrast, the current study shows that atypical tubal metaplasia displays, at most, only focal, weak immunoreactivity with p53, and is frequently p53 negative. This pattern of expression was also seen in typical tubal metaplasia, which has been reported in a previous study.13

Ki-67

Comprehensive, well-known analysis has shown that Ki-67 is expressed exclusively in proliferating cells, and that immunostaining with a monoclonal antibody for Ki-67 is a reliable method of evaluating the growth fraction of normal and neoplastic human cell populations.14 Studies have also shown that Ki-67 proliferation indices are increased in numerous human malignancies, including high-grade endometrial cancer, as compared with post-menopausal (atrophic) endometrium.15 High proliferation indices with Ki-67 are also seen in invasive 7, 16 and intraepithelial serous carcinoma.12 In contrast, our findings show that the majority of atypical tubal metaplasia is either negative for Ki-67 or shows a low proliferation index, with Ki-67 immunopositivity limited to less than 5% of atypical cells. This pattern of expression is similar to that seen in typical tubal metaplasia.

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)

Telomeres are specialized nucleoproteins in repetitive sequences present at the ends of chromosomes that provide protection from chromosome degradation and end-to-end fusion. With each cell division, the length of telomeres is progressively shortened until the chromosome becomes unstable, at which point cell death occurs; a process known as replicative senescence.17 The telomerase enzyme is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase that catalyzes the addition and maintenance of telomeric repeat sequences to chromosome ends. Activation of this enzyme enables cells to overcome replicative senescence and divide indefinitely.18, 19 Telomerase activity is considered a marker of cell proliferation,20 as it is present in normal tissues that are highly proliferative, such as oral mucosa,21 the basal layer of epidermis,22 and proliferative-phase endometrium.23 Telomerase activity is also present in a high percentage of human tumor types.24 In malignancies, telomerase activity may simply mirror the fraction of proliferating cells;20 however, it is also hypothesized that tumor cells may independently upregulate telomerase levels.25 Studies have revealed that there are two major subunits contributing to in vitro activity of the telomerase enzyme complex: an intrinsic RNA component (TERC) containing a template region that binds to telomeric repeats; and a catalytic subunit with reverse transcriptase activity (TERT).26, 27 Although TERC is constitutively present in normal and cancer cells, TERT expression is limited almost exclusively to cancer cells.28 Brustmann8, 29 has reported the immunohistochemical reactivity of TERT in numerous human cancers, including uterine endometrioid and serous carcinoma, but not in benign lesions such as serous cystadenoma. Our study corroborates literature reports of TERT immunopositivity in uterine serous carcinoma and also shows that, in contrast, atypical tubal metaplasia is completely negative for TERT.

Long-term outcome

Atypical tubal metaplasia is worrisome in endometrial biopsy and curettage specimens, as it displays a superficial resemblance to invasive or intraepithelial serous carcinoma. Uterine serous carcinoma is well known for exhibiting aggressive behavior. After its initial biopsy diagnosis, early metastasis is often discovered at the time of surgery, resulting in an upstaging of the cancer.3 Serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma is commonly associated with extrauterine serous carcinoma.4, 12, 30, 31 Because of the clinically aggressive nature of these lesions, surgical management and staging is recommended.32 Our study shows that the clinical behavior of atypical tubal metaplasia differs from that of invasive or intraepithelial serous carcinoma, as after an average follow-up period of 5 years, the presence of atypical tubal metaplasia in endometrial samplings did not increase the risk of developing hyperplasia or malignancy.

In conclusion, the findings of this study are reassuring as they show that atypical tubal metaplasia displays immunostaining patterns with p53, Ki-67, and TERT that are similar to typical tubal metaplasia and distinct from uterine serous carcinoma or serous endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma. Therefore, although atypical tubal metaplasia in endometrial samplings may seem histologically worrisome for malignancy, its immunoprofile is not consistent with that of invasive or intraepithelial serous carcinoma. In addition our long-term follow-up study shows that atypical tubal metaplasia displays no increased incidence of atypical endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma compared with typical tubal metaplasia. These findings suggest that atypical tubal metaplasia is most likely degenerative or reactive in etiology; the entity per se is not a direct precursor to atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma; and its presence in endometrial specimens does not portend a greater risk for patients to develop these lesions, as compared with the control population. Recognition of this morphologic entity in endometrial biopsies is important as it may prevent unwarranted aggressive clinical management.

References

Crum CP, Nucci MR, Mutter GL . Altered endometrial differentiation (metaplasia) In: Crum CP, Lee KR (eds). Diagnostic gynecologic and obstetric pathology. Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, 2006, pp 519–544.

Silverberg SG, Kurman RJ, Nogales F, et al. Epithelial tumours and related lesions In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P (eds). Pathology and genetics: tumours of the breast and female genital organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2003, pp 221–232.

Goff BA, Kato D, Schmidt RA, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of metastatic spread. Gynecol Oncol 1994;54:264–268.

Carcangiu ML, Tan LK, Chambers JT . Stage IA uterine serous carcinoma: a study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:1507–1514.

King SA, Adas AA, LiVolsi VA, et al. Expression and mutation analysis of the p53 gene in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer 1995;75:2700–2705.

Tashiro H, Isacson C, Levine R, et al. p53 gene mutations are common in uterine serous carcinoma and occur early in their pathogenesis. Am J Pathol 1997;150:177–185.

McCluggage WG . A critical appraisal of the value of immunohistochemistry in diagnosis of uterine neoplasms. Adv Anat Pathol 2004;11:162–171.

Brustmann H . Immunohistochemical detection of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), topoisomerase IIα expression, and apoptosis in endometrial adenocarcinoma and atypical hyperplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2005;24:184–192.

Harris CC . 1995 Deichmann lecture—p53 tumor suppressor gene: at the crossroads of molecular carcinogenesis, molecular epidemiology and cancer risk assessment. Toxicol Lett 1995;82/83:1–7.

Vojteĕsšek B, Bártek J, Midgley CA, et al. An immunochemical analysis of the human nuclear phosphoprotein p53: new monoclonal antibodies and epitope mapping using recombinant p53. J Immunol Methods 1992;151:237–244.

Sherman ME, Bur ME, Kurman RJ . p53 in endometrial cancer and its putative precursors: evidence for diverse pathways of tumorigenesis. Human Pathol 1995;26:1268–1274.

Wheeler DT, Bell KA, Kurman RJ, et al. Minimal uterine serous carcinoma: diagnosis and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:797–806.

Quddus MR, Sung CJ, Zheng W, et al. p53 immunoreactivity in endometrial metaplasia with dysfunctional bleeding. Histopathology 1999;35:44–49.

Gerder J, Lemke H, Baisch H, et al. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody ki-67. J Immunol 1984;133:1710–1715.

Morsi HM, Leers MPG, Jäger W, et al. The patterns of expression of an apoptosis-related CK18 neoepitope, the bcl-2 proto-oncogene, and the ki67 proliferation marker in the normal, hyperplastic, and malignant endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:118–126.

Iida T, Hamano M, Yoshida N, et al. Establishment and characterization of two cell lines (HEC-155, HEC-180) derived from uterine papillary serous adenocarcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2004;25:423–427.

Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW . Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 1990;345:458–460.

Counter CM, Avilion AA, LeFeuvre CE, et al. Telomere shortening associated with chromosome instability is arrested in immortal cells which express telomerase activity. EMBO J 1992;11:1921–1929.

Harley CB, Villeponteau B . Telomeres and telomerase in aging and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1995;5:249–255.

Belair CD, Yeager TR, Lopez PM, et al. Telomerase activity: a biomarker of cell proliferation, not malignant transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997;94:13677–13682.

Kannan S, Tahara H, Yokozaki H, et al. Telomerase activity in premalignant and malignant lesions of human oral mucosa. Cancer Epidem Biomarkers Prevent 1997;6:413–420.

Härle-Bachor C, Boulamp P . Telomerase activity in the regenerative basal layer of the epidermis in human skin and in immortal and carcinoma-derived skin keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:6476–6481.

Kyo S, Takakura M, Kohama T, et al. Telomerase activity in the human endometrium. Cancer Res 1997;57:610–614.

Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 1994;266:2011–2015.

Wynford-Thomas D . Cellular senescence and cancer. J Pathol 1999;187:100–111.

Nakamura TM, Morin GB, Chapman KB, et al. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science 1997;277:955–959.

Meyerson M, Counter CM, Eaton EN, et al. hEST2, the putative human telomerase catalytic subunit gene, is upregulated in tumor cells and during immortalization. Cell 1997;90:785–795.

Kyo S, Masutomi K, Maida Y, et al. Significance of immunological detection of human telomerase reverse transcriptase: re-evaluation of expression and localization of human telomerase reverse transcriptase. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;163:859–867.

Brustmann H . Immunohistochemical detection of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) and c-kit in serous ovarian carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gynecol Oncol 2005;98:396–402.

Zheng W, Schwartz PE . Serous EIC as an early form of uterine papillary serous carcinoma: recent progress in understanding its pathogenesis and current opinions regarding pathologic and clinical management. Gynecol Oncol 2005;95:579–582.

Hui P, Kelly M, O’Malley DM, et al. Minimal uterine serous carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 40 cases. Mod Pathol 2005;18:75–82.

Faratian D, Stillie A, Busby-Earle RMC, et al. A review of the pathology and management of uterine papillary serous carcinoma and correlation with outcome. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:972–978.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Portions of this study were presented in part at the 92nd, 93rd, and 98th annual meetings of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology in Washington, DC, USA, March 2003, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, March 2004, and Boston, MA, USA, March 2009, respectively.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, R., Peng, SL., Liu, F. et al. Tubal metaplasia of the endometrium with cytologic atypia: analysis of p53, Ki-67, TERT, and long-term follow-up. Mod Pathol 24, 1254–1261 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.78

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.78

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clear cell endometrial carcinoma precursors: presentation of two cases and diagnostic issues

Diagnostic Pathology (2021)

-

Vorläuferläsionen der Endometriumkarzinome

Der Pathologe (2019)