Abstract

Social ties often seem symmetric, but they need not be1,2,3,4,5. For example, a person might know a stranger better than the stranger knows them. We explored whether people overlook these asymmetries and what consequences that might have for people’s perceptions and actions. Here we show that when people know more about others, they think others know more about them. Across nine laboratory experiments, when participants learned more about a stranger, they felt as if the stranger also knew them better, and they acted as if the stranger was more attuned to their actions. As a result, participants were more honest around known strangers. We tested this further with a field experiment in New York City, in which we provided residents with mundane information about neighbourhood police officers. We found that the intervention shifted residents’ perceptions of officers’ knowledge of illegal activity, and it may even have reduced crime. It appears that our sense of anonymity depends not only on what people know about us but also on what we know about them.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The Open Science Framework page for this project (https://osf.io/mkgwr/) includes all data from laboratory experiments and all data necessary to reproduce the results of the field experiment.

Code availability

The codes for running the laboratory experiments online and for analysing the data from the field experiment are available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mkgwr/).

References

Krackhardt, D. & Kilduff, M. Whether close or far: social distance effects on perceived balance in friendship networks. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76, 770–782 (1999).

Davis, J. A. In Theories of Cognitive Consistency (eds Abelson, R. P. et al.) 544–550 (Rand McNally, 1968).

Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (Wiley, 1958).

DeSoto, C. B. Learning a social structure. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 60, 417–421 (1960).

Freeman, L. C. Filling in the blanks: a theory of cognitive categories and the structure of social affiliation. Soc. Psychol. Q. 55, 118–127 (1992).

Rand, D. G. et al. Social heuristics shape intuitive cooperation. Nat. Commun. 5, 3677 (2014).

Holoien, D. S., Bergsieker, H. B., Shelton, J. N. & Alegre, J. M. Do you really understand? Achieving accuracy in interracial relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 76–92 (2015).

Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L. & Gilovich, T. Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 327–339 (2004).

Nickerson, R. S. How we know—and sometimes misjudge—what others know: imputing one’s own knowledge to others. Psychol. Bull. 125, 737–759 (1999).

Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K. & Medvec, V. H. The illusion of transparency: biased assessments of others’ ability to read one’s emotional states. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 332–346 (1998).

Gilovich, T. & Savitsky, K. The spotlight effect and the illusion of transparency: egocentric assessments of how we’re seen by others. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 8, 165–168 (1999).

Milgram, S. The experience of living in cities. Science 167, 1461–1468 (1970).

Diener, E., Fraser, S. C., Beaman, A. L. & Kelem, R. T. Effects of deindividuation variables on stealing among Halloween trick-or-treaters. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 33, 178–183 (1976).

Zhong, C., Bohns, V. K. & Gino, F. Good lamps are the best police: darkness increases dishonesty and self-interested behavior. Psychol. Sci. 21, 311–314 (2010).

Andreoni, J. & Petrie, R. Public goods experiments without confidentiality: a glimpse into fund-raising. J. Public Econ. 88, 1605–1623 (2004).

Yoeli, E., Hoffman, M., Rand, D. & Nowak, M. Powering up with indirect reciprocity in a large-scale field experiment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10424–10429 (2013).

Ernest-Jones, M., Nettle, D. & Bateson, M. Effects of eye images on everyday cooperative behavior: a field experiment. Evol. Hum. Behav. 32, 172–178 (2011).

Pronin, E., Kruger, J., Savitsky, K. & Ross, L. You don’t know me, but I know you: the illusion of asymmetric insight. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 639–656 (2001).

Lakens, D. Equivalence tests: a practical primer for t tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 8, 355–362 (2017).

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D. & Hayes, A. F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav. Res. 42, 185–227 (2007).

Parks, R. B., Mastrofski, S. D., DeJong, C. & Gray, M. K. How officers spend their time with the community. Justice Q. 16, 483–518 (1999).

Ba, B. A., Knox, D., Mummolo, J. & Rivera, R. The role of officer race and gender in police-civilian interactions in Chicago. Science 371, 696–702 (2021).

Fryer, R. G. An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. J. Pol. Econ. 127, 1210–1261 (2019).

Voigt, R. et al. Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6521–6526 (2017).

Braga, A. A., Papachristos, A. V. & Hureau, D. M. The effects of hot spots policing on crime: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Justice Q. 31, 633–663 (2014).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Proactive Policing: Effects on Crime and Communities (The National Academies Press, 2018).

National Research Council. Fairness and Effectiveness in Policing: The Evidence (The National Academies Press, 2004).

Sherman, L. W. & Eck, J. in Evidence Based Crime Prevention (eds Sherman, L. W. et al.) 295–329 (Routledge, 2002).

Peyton, K., Sierra-Arévalo, M. & Rand, D. G. A field experiment on community policing and police legitimacy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 19894–19898 (2019).

Owens, E., Weisburd, D., Amendola, K. L. & Alpert, G. P. Can you build a better cop? Experimental evidence on supervision, training, and policing in the community. Criminol. Public Policy 17, 41–87 (2018).

Sunshine, J. & Tyler, T. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law Soc. Rev. 37, 513–548 (2003).

Chalfin, C., Hansen, B., Weisburst, E. K. & Williams, M. C. Police force size and civilian race. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights (in the press).

Belloni, A., Chernozhukov, V. & Hansen, C. High-dimensional methods and inference on structural and treatment effects. J. Econ. Perspect. 28, 29–50 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institute of Justice (award number 2013-R2-CX-0006). We are grateful to the New York City Police Department, particularly T. Coffey and D. Williamson in the Office of Management Analysis and Planning. Points of view or opinions contained within this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the New York City Police Department. We also thank the New York City Housing Authority for their assistance with the field experiment. Throughout this project, ideas42 was an essential research partner. We are also grateful to H. Furstenberg-Beckman for thoughtful guidance; A. Alhadeff and W. Tucker for valuable assistance; Crime Lab New York for critical support in the planning and evaluation of the policing intervention, particularly R. Ander, M. Barron, A. Chalfin, K. Falco, V. Gilbert, D. Hafetz, B. Jakubowski, Z. Jelveh, K. Nguyen, L. Parker, J. Lerner, H. Golden, G. Stoddard and N. Weil; V. Nguyen for her support as a research assistant; and J. Ludwig, S. Mullainathan, A. Kumar, E. O’Brien and F. Goncalves for insightful feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.S. developed the hypotheses. A.K.S. designed, conducted and analysed the laboratory experiments. A.K.S. and M.L. designed the field intervention. M.L. led the analysis of the field intervention. A.K.S. and M.L. contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Outreach cards.

A sample outreach card (front and back) used in the field intervention. Identifying information has been redacted.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Outreach letters.

A sample letter used in the field intervention. Identifying information has been redacted.

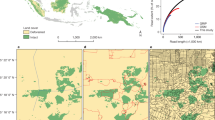

Extended Data Fig. 3 Distribution of point estimates for treatment effect.

As a robustness check, we conducted analyses for various radii ranging up to three blocks around developments: 65 ft., 100 ft., 150 ft., 200 ft., 250 ft., 300 ft., 400 ft., 500 ft., and 750 ft. And, for each radius, we conducted analyses for cumulative time intervals ranging from one month after the intervention (i.e., February 2018) to the first nine months after the intervention (i.e., February through October 2018). Varying both of these dimensions produced 81 sets of results, based on our primary specification applied to each radius and time interval (see Supplementary Information C.3). This figure shows the distribution of point estimates for the crime reductions across these analyses, along with an Epanechnikov kernel density function over the distribution. The red dot highlights where the 250-ft, 3-month result falls in the distribution, suggesting it is in line with the central estimates across all 81 analyses.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Heat map of P-values for treatment effect over time and distance.

As a robustness check, we conducted analyses for various radii ranging up to three blocks around developments: 65 ft., 100 ft., 150 ft., 200 ft., 250 ft., 300 ft., 400 ft., 500 ft., and 750 ft. And, for each radius, we conducted analyses for cumulative time intervals ranging from one month after the intervention (i.e., February 2018) to the first nine months after the intervention (i.e., February through October 2018). Varying both of these dimensions produced 81 sets of results. This figure shows a heat map of P-values across these 81 specifications, with the 250-ft, 3-month result outlined in blue. P-values are from two-tailed tests based on our primary specification applied to each radius and time interval (see Supplementary Information C.3).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains the following sections: A. Lab experiment methods, materials, and results; B. Field experiment methods and materials; C. Field experiment results, tables, and figures; D. Software Used; E. Supplementary references.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, A.K., LaForest, M. Knowledge about others reduces one’s own sense of anonymity. Nature 603, 297–301 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04452-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04452-3

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.