Abstract

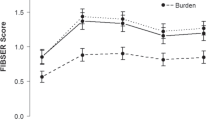

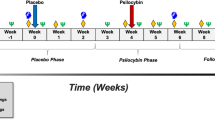

Recent studies and anecdotal reports suggest that psychedelics can improve mood states, even at low doses. However, few placebo-controlled studies have examined the acute effects of low doses of LSD in individuals with psychiatric symptoms. In the current study, we examined the acute and sub-acute effect of a low dose of LSD (26 µg) on subjective effects and mood in volunteers with mild depressed mood. The study used a randomized, double-blind, crossover design to compare the effects of LSD in two groups of adults: participants who scored high (≥17; n = 20) or low (<17; n = 19) on the Beck Depression-II inventory (BDI) at screening. Participants received a single low dose of LSD (26 µg) and placebo during two 5-h laboratory sessions, separated by at least one week. Subjective, physiological, and mood measures were assessed at regular intervals throughout the sessions, and behavioral measures of creativity and emotion recognition were obtained at expected peak effect. BDI depression scores and mood ratings were assessed 48-h after each session. Relative to placebo, LSD (26 µg) produced expected, mild physiological and subjective effects on several measures in both groups. However, the high BDI group reported significantly greater drug effects on several indices of acute effects, including ratings of vigor, elation, and affectively positive scales of a measure of psychedelic effects (5D-ASC). The high BDI group also reported a greater decline in BDI depression scores 48-h after LSD, compared to placebo. These findings suggest that an acute low dose of LSD (26 µg) elicits more pronounced positive mood and stimulant-like effects, as well as stronger altered states of consciousness in individuals with depressive symptoms, compared to non-depressed individuals.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 13 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $19.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

SAMHSA, S.A.A.M.H.S.A., Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2021, HHS.

WHO, W.H.O. Depressive disorder (depression). 2023; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

Goodwin GM, et al. Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1637–48.

Griffiths RR, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1181–97.

Ross S, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1165–80.

Sloshower J, et al. Psilocybin-assisted therapy for major depressive disorder: an exploratory placebo-controlled, fixed-order trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2023;37:698–706.

Holze F, et al. Lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted therapy in patients with anxiety with and without a life-threatening illness: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;93:215–23.

Raison CL, et al. Effects of naturalistic psychedelic use on depression, anxiety, and well-being: associations with patterns of use, reported harms, and transformative mental states. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:831092.

Lea T, et al. Microdosing psychedelics: motivations, subjective effects and harm reduction. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;75:102600.

Fadiman, J., The psychedelic explorer’s guide: safe, therapeutic, and sacred journeys. Park Street Press; 2011. p. 352.

Hutten N, Mason NL, Dolder PC, Kuypers KPC. Self-rated effectiveness of microdosing with psychedelics for mental and physical health problems among microdosers. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:672.

de Wit H, et al. Repeated low doses of LSD in healthy adults: a placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Addict Biol. 2022;27:e13143.

Bershad AK, et al. Acute subjective and behavioral effects of microdoses of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy human volunteers. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;86:792–800.

Murray CH, et al. Low doses of LSD reduce broadband oscillatory power and modulate event-related potentials in healthy adults. Psychopharmacology. 2022;239:1735–47.

Murphy RJ, et al. Acute mood-elevating properties of microdosed lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy volunteers: a home-administered randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;94:511–21.

Polito V, Liknaitzky, P. The emerging science of microdosing: A systematic review of research on low dose psychedelics (1955-2021) and recommendations for the field. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;139:104706.

Cavanna F, et al. Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:307.

Marschall J, et al. Psilocybin microdosing does not affect emotion-related symptoms and processing: a preregistered field and lab-based study. J Psychopharmacol. 2022;36:97–113.

Glazer J, et al. Low doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) increase reward-related brain activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48:418–26.

Szigeti B, et al. Self-blinding citizen science to explore psychedelic microdosing. eLife. 2021;10:e62878.

Kaertner LS, et al. Positive expectations predict improved mental-health outcomes linked to psychedelic microdosing. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1941.

Holze F, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lysergic acid diethylamide microdoses in healthy participants. Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;109:658–66.

Holze F, et al. Acute dose-dependent effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:537–44.

Passie T, et al. The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14:295–314.

Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II), in APA PsycTests. 1996.

Association I.S.M. Beck Depression Inventory Scoring. Available from: https://www.ismanet.org/doctoryourspirit/pdfs/Beck-Depression-Inventory-BDI.pdf.

OHSU. Beck Depression Inventory. Available from: https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-06/Beck%20Depression%20Inventory.pdf.

MAPS. Beck Depression Inventory II. Scoring guide]. Available from: https://maps.org/images/pdf/Beck-Depression-Inventory-Real-Time-Report.pdf.

University of Wisconsin-Madison. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Available from: https://arc.psych.wisc.edu/self-report/beck-depression-inventory-bdi/.

Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Utility of subjective-effects measurements in assessing abuse liability of drugs in humans. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1563–70.

Morean ME, et al. The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology. 2013;227:177–92.

Martin WR, Sloan JW, Sapira JD, Jasinski DR. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clin Pharm Ther. 1971;12:245–58.

McNair D, Lorr M, POMS Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service. 1971.

de Wit H, Griffiths RR. Testing the abuse liability of anxiolytic and hypnotic drugs in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1991;28:83–111.

Dittrich A. The standardized psychometric assessment of altered states of consciousness (ASCs) in humans. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31:80–4.

Studerus E, Gamma A, Vollenweider FX. Psychometric evaluation of the altered states of consciousness rating scale (OAV). PLoS One. 2010;5:e12412.

Schmid Y, et al. Acute effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:544–53.

Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338:68–72.

Ly C, et al. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3170–82.

Moliner R, et al. Psychedelics promote plasticity by directly binding to BDNF receptor TrkB. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26:1032–41.

Long EE, Haraden DA, Young JF, Hankin BL. Longitudinal patterning of depression repeatedly assessed across time among youth: different trajectories in self-report questionnaires and diagnostic interviews. Psychol Assess. 2020;32:872–82.

Balaet M. Psychedelic cognition-the unreached frontier of psychedelic science. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:832375.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Mass Spectrometry Core in Research Resources Center of University of Illinois at Chicago. Clinical trials registry: Clinicaltrials.gov, Mood Effects of Serotonin Agonists (NCT03790358).

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grant DA02812). HM was supported by T32GM07019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HdW, HM, and RL contributed to the design and implementation of the study. IT carried out the data collection. HM analyzed the data. HdW and HM prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HdW is on the Board of Directors of PharmAla Biotech and consultant to Awakn Life Sciences and Gilgamesh Pharmaceuticals. These were unrelated to the present research. HM, RL, and IT report no conflicts.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Molla, H., Lee, R., Tare, I. et al. Greater subjective effects of a low dose of LSD in participants with depressed mood. Neuropsychopharmacol. 49, 774–781 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-023-01772-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-023-01772-4

This article is cited by

-

Are “mystical experiences” essential for antidepressant actions of ketamine and the classic psychedelics?

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2024)