Abstract

Introduction

Childhood obesity increased in the first year of COVID-19 with significant disparities across race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Social distancing led to fewer physical activity opportunities but increased screen time and high-calorie food consumption, all co-determined by neighborhood environments. This study aimed to test the moderation effects of neighborhood socioeconomic and built environments on obesity change during COVID-19.

Methods

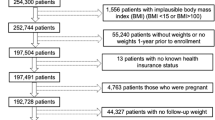

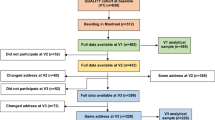

Using electronic health records from a large pediatric primary care network in 2018–2022, we cross-sectionally examined 163,042 well visits of 2–17-year-olds living in Philadelphia County in order to examine (1) the pandemic’s effect on obesity prevalence and (2) moderation by census-tract-level neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, crime, food and physical activity-related environments using interrupted-time-series analysis, Poisson regression, and logistic regression.

Results

Weekly obesity prevalence increased by 4.9 percent points (pp) during the pandemic (January 2021–August 2022) compared to pre-pandemic (March 2018–March 2020) levels. This increase was pronounced across all age groups, racially/ethnically minoritized groups, and insurance types (ranging from 2.0 to 6.4 pp) except the Non-Hispanic-white group. The increase in obesity among children racially/ethnically minoritized groups was significantly larger in the neighborhoods with high social vulnerability (3.3 pp difference between high and low groups), and low collective efficacy (2.0 pp difference between high and low groups) after adjusting for age, sex, and insurance type.

Conclusions

Racially/ethnically minoritized children experienced larger obesity increases during the pandemic, especially those in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. However, the buffering effect of community collective efficacy on the disparities underscores the importance of environments in pediatric health.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data analyzed during this study are held securely by the CHOP Arcus team. Due to privacy concerns and regulatory restrictions, the data cannot be made available publicly. Interested researchers may contact the CHOP Arcus team to discuss the feasibility of accessing the study data.

References

Boutari C, Mantzoros CS. A 2022 update on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: as its twin COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism. 2022;133:155217. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.METABOL.2022.155217.

Restrepo BJ. Obesity prevalence Among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63:102–6.

Woolford SJ, Sidell M, Li X, Else V, Young DR, Resnicow K, et al. Changes in body mass index among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2021;326:1434–6.

Jenssen BP, Kelly MK, Powell M, Bouchelle Z, Mayne SL, Fiks AG. COVID-19 and changes in child obesity. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2021050123. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2021-050123.

Lange SJ, Kompaniyets L, Freedman DS, Kraus EM, Porter R, Blanck HM, et al. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years — United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1278–83.

Daniels KM, Schinasi LH, Auchincloss AH, Forrest CB, Diez Roux AV. The built and social neighborhood environment and child obesity: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Prev Med (Baltim). 2021;153:106790.

Dunton GF, Do B, Wang SD. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1351. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-020-09429-3.

Obesity, Race/Ethnicity, and COVID-19 | Overweight & Obesity | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/obesity-and-covid-19.html. Accessed 1 May 2022.

Kondo MC, Felker-Kantor E, Wu K, Gustat J, Morrison CN, Richardson L, et al. Stress and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of neighborhood context. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2779. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH19052779.

Zenic N, Taiar R, Gilic B, Blazevic M, Maric D, Pojskic H, et al. Levels and changes of physical activity in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: contextualizing urban vs. rural living environment. Appl Sci. 2020;10:3997.

Mitra R, Moore SA, Gillespie M, Faulkner G, Vanderloo LM, Chulak-Bozzer T, et al. Healthy movement behaviours in children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the role of the neighbourhood environment. Health Place. 2020;65:102418.

Winston P. Office of Human Services Policy USD of Health & HS. COVID-19 and economic opportunity: unequal effects on economic need and program response. 2021 https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/265391/covid-19-human-service-response-brief.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2023.

Karmakar M, Lantz PM, Tipirneni R. Association of social and demographic factors with COVID-19 incidence and death rates in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2036462. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.36462.

Khanijahani A, Iezadi S, Gholipour K, Azami-Aghdash S, Naghibi D. A systematic review of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in COVID-19. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:1–30.

CDC – Community Profile – Philadelphia, PA – Communities Putting Prevention to Work. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/programs/communitiesputtingpreventiontowork/communities/profiles/both-pa_philadelphia.htm. Accessed 21 Jun 2023.

Bjornstrom EES. An examination of the relationship between neighborhood income inequality, social resources, and obesity in Los Angeles county. Am J Health Promot. 2011;26:109–15.

Kranjac AW, Kranjac D, Kain ZN, Ehwerhemuepha L, Jenkins BN. Obesity heterogeneity by neighborhood context in a largely Latinx sample. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40615-023-01578-6.

Sharifi M, Sequist TD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Melly SJ, Duncan DT, Horan CM, et al. The role of neighborhood characteristics and the built environment in understanding racial/ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Prev Med (Baltim). 2016;91:103–9.

CDC. Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Modified z-scores in the CDC growth charts. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/resources/biv-cutoffs.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2022.

The US CDC 2000 Growth Charts. Defining childhood obesity. 19 Jul 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html.

Mayne SL, Hannan C, Davis M, Young JF, Kelly MK, Powell M, et al. COVID-19 and adolescent depression and suicide risk screening outcomes. Pediatrics. 2021;148:e2021051507. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2021-051507.

CDC: Department of Health and Human Services. Dear Colleague letter- DSTDP Lab and Drug Shortages. https://www.cdc.gov/std/dstdp/dcl/DCL-Diagnostic-Test-Shortage.pdf. Accessed 2 Jun 2022.

Yu CY, Woo A, Emrich CT, Wang B. Social Vulnerability Index and obesity: an empirical study in the US. Cities. 2020;97:102531.

Aris IM, Perng W, Dabelea D, Padula AM, Alshawabkeh A, Vélez-Vega CM, et al. Associations of neighborhood opportunity and social vulnerability with trajectories of childhood body mass index and obesity among US children. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:E2247957.

Khazanchi R, Beiter ER, Gondi S, Beckman AL, Bilinski A, Ganguli I. County-level association of social vulnerability with COVID-19 cases and deaths in the USA. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:2784–7.

Krieger N, Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the index of concentration at the extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:256.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program. CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index Database. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/documentation/pdf/SVI2018Documentation_01192022_1.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

diversitydatakids.org. 2022. Child Opportunity Index 2.0 database. https://data.diversitydatakids.org/dataset/coi20-child-opportunity-index-2-0-database?_external=True. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD. Using the methods of the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project to monitor COVID-19 inequities and guide action for social justice. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/thegeocodingproject/covid-19-resources/. Accessed 17 Jun 2023.

Philadelphia police department. Crime Maps and Stats. https://www.phillypolice.com/crime-maps-stats. Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. EnviroAtlas project. https://www.epa.gov/enviroatlas. Accessed 8 Jun 2022.

Tsai WL, Nash MS, Rosenbaum DJ, Prince SE, D’Aloisio AA, Neale AC, et al. Types and spatial contexts of neighborhood greenery matter in associations with weight status in women across 28 U.S. communities. Environ Res. 2021;199:111327.

Knobel P, Kondo M, Maneja R, Zhao Y, Dadvand P, Schinasi LH. Associations of objective and perceived greenness measures with cardiovascular risk factors in Philadelphia, PA: a spatial analysis. Environ Res. 2021;197:110990. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENVRES.2021.110990.

Singleton CR, Winata F, Parab KV, Adeyemi OS, Aguiñaga S. Violent crime, physical inactivity, and obesity: examining spatial relationships by racial/ethnic composition of community residents. J Urban Health. 2023;100:279–89.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Smart Location Mapping: National Walkability Index. https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/smart-location-mapping#walkability. Accessed 8 Jun 2022.

Parks & Recreation Program Sites – OpenDataPhilly. https://opendataphilly.org/datasets/parks-recreation-program-sites/. Accessed 5 Jul 2023.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S. Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Census tract level state maps of the modified food environment index (mRFEI). https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/census-tract-level-state-maps-mrfei_TAG508.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

Esri Consumer Spending: Esri Methodology Statement, June 2021. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/ba42e0b000d0430faf8764931fc7e75e. Accessed 7 Jun 2022.

Cohen DA, Finch BK, Bower A, Sastry N. Collective efficacy and obesity: the potential influence of social factors on health. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:769–78.

Hutchinson RN, Putt MA, Dean LT, Long JA, Montagnet CA, Armstrong K. Neighborhood racial composition, social capital and black all-cause mortality in Philadelphia. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1859–65.

Mayne SL, Hannan C, Difiore G, Virudachalam S, Glanz K, Fiks AG. Associations of neighborhood safety and collective efficacy with dietary intake among preschool-aged children and mothers. Child Obes. 2022;18:120–31.

Public Health Management Corporation. Southeastern Pennsylvania Household Health Survey. https://research.phmc.org/52-project-spotlight/248-southeastern-pennsylvania-household-health-survey. Accessed 8 Jun 2022.

Mayne SL, Kelleher S, Hannan C, Kelly MK, Powell M, Dalembert G, et al. Neighborhood greenspace and changes in pediatric obesity during COVID-19. Am J Prev Med. 2023;64:33.

Child ST, Kaczynski AT, Walsemann KM, Fleischer N, McLain A, Moore S. Socioeconomic differences in access to neighborhood and network social capital and associations with body mass index among black Americans. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34:150–60.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–24.

Veenstra G. Social capital, SES and health: an individual-level analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:619–29.

Halbert CH, Bellamy S, Briggs V, Bowman M, Delmoor E, Kumanyika S, et al. Collective efficacy and obesity-related health behaviors in a community sample of African Americans. J Community Health. 2014;39:124–31.

Dulin A, Risica PM, Mello J, Ahmed R, Carey KB, Cardel M, et al. Examining neighborhood and interpersonal norms and social support on fruit and vegetable intake in low-income communities. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:455. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-018-5356-2.

Kawachi I. Social capital and community effects on population and individual health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:120–30.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rachel Sanderlin and Vivian Shoukrun for their assistance in editing.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (K01HL155860) and Clinical Futures, a Research Center of Emphasis at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect the official policy of the NHLBI and CHOP. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM conceptualized and designed the study, extracted and analyzed data, interpreted results, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. VT contributed to the study design, extracted and analyzed data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. SM contributed to the study design, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, J., Tam, V. & Mayne, S. Pediatric obesity during COVID-19: the role of neighborhood social vulnerability and collective efficacy. Int J Obes 48, 550–556 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-023-01448-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-023-01448-5