Abstract

The fact that the identity of the cells that initiate metastasis in most human cancers is unknown hampers the development of antimetastatic therapies. Here we describe a subpopulation of CD44bright cells in human oral carcinomas that do not overexpress mesenchymal genes, are slow-cycling, express high levels of the fatty acid receptor CD36 and lipid metabolism genes, and are unique in their ability to initiate metastasis. Palmitic acid or a high-fat diet specifically boosts the metastatic potential of CD36+ metastasis-initiating cells in a CD36-dependent manner. The use of neutralizing antibodies to block CD36 causes almost complete inhibition of metastasis in immunodeficient or immunocompetent orthotopic mouse models of human oral cancer, with no side effects. Clinically, the presence of CD36+ metastasis-initiating cells correlates with a poor prognosis for numerous types of carcinomas, and inhibition of CD36 also impairs metastasis, at least in human melanoma- and breast cancer-derived tumours. Together, our results indicate that metastasis-initiating cells particularly rely on dietary lipids to promote metastasis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

13 December 2016

The received date was corrected in the HTML.

04 January 2017

The Competing Interests statement and the Acknowledgements funding information were updated.

References

Oskarsson, T., Batlle, E. & Massagué, J. Metastatic stem cells: sources, niches, and vital pathways. Cell Stem Cell 14, 306–321 (2014)

Nieman, K. M. et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat. Med. 17, 1498–1503 (2011)

Kalluri, R. & Zeisberg, M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 392–401 (2006)

Zhang, X. H. et al. Selection of bone metastasis seeds by mesenchymal signals in the primary tumor stroma. Cell 154, 1060–1073 (2013)

Calon, A. et al. Dependency of colorectal cancer on a TGF-β-driven program in stromal cells for metastasis initiation. Cancer Cell 22, 571–584 (2012)

Goel, H. L. & Mercurio, A. M. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 871–882 (2013)

Sevenich, L. et al. Analysis of tumour- and stroma-supplied proteolytic networks reveals a brain-metastasis-promoting role for cathepsin S. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 876–888 (2014)

Valiente, M. et al. Serpins promote cancer cell survival and vascular co-option in brain metastasis. Cell 156, 1002–1016 (2014)

Obenauf, A. C. et al. Therapy-induced tumour secretomes promote resistance and tumour progression. Nature 520, 368–372 (2015)

Lu, X. et al. VCAM-1 promotes osteolytic expansion of indolent bone micrometastasis of breast cancer by engaging α4β1-positive osteoclast progenitors. Cancer Cell 20, 701–714 (2011)

Chen, Q., Zhang, X. H. & Massagué, J. Macrophage binding to receptor VCAM-1 transmits survival signals in breast cancer cells that invade the lungs. Cancer Cell 20, 538–549 (2011)

Chaffer, C. L. & Weinberg, R. A. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 331, 1559–1564 (2011)

Peinado, H. et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 18, 883–891 (2012)

Oskarsson, T. et al. Breast cancer cells produce tenascin C as a metastatic niche component to colonize the lungs. Nat. Med. 17, 867–874 (2011)

McAllister, S. S. & Weinberg, R. A. The tumour-induced systemic environment as a critical regulator of cancer progression and metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 717–727 (2014)

Paolino, M. et al. The E3 ligase Cbl-b and TAM receptors regulate cancer metastasis via natural killer cells. Nature 507, 508–512 (2014)

Wculek, S. K. & Malanchi, I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature 528, 413–417 (2015)

Zomer, A. et al. In vivo imaging reveals extracellular vesicle-mediated phenocopying of metastatic behavior. Cell 161, 1046–1057 (2015)

Zhou, W. et al. Cancer-secreted miR-105 destroys vascular endothelial barriers to promote metastasis. Cancer Cell 25, 501–515 (2014)

Yumoto, K., Berry, J. E., Taichman, R. S. & Shiozawa, Y. A novel method for monitoring tumor proliferation in vivo using fluorescent dye DiD. Cytometry A 85, 548–555 (2014)

Prince, M. E. et al. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 973–978 (2007)

Harper, L. J., Piper, K., Common, J., Fortune, F. & Mackenzie, I. C. Stem cell patterns in cell lines derived from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med . 36, 594–603 (2007)

Biddle, A. et al. Cancer stem cells in squamous cell carcinoma switch between two distinct phenotypes that are preferentially migratory or proliferative. Cancer Res. 71, 5317–5326 (2011)

Coburn, C. T. et al. Defective uptake and utilization of long chain fatty acids in muscle and adipose tissues of CD36 knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32523–32529 (2000)

Ibrahimi, A. et al. Muscle-specific overexpression of FAT/CD36 enhances fatty acid oxidation by contracting muscle, reduces plasma triglycerides and fatty acids, and increases plasma glucose and insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26761–26766 (1999)

Pepino, M. Y., Kuda, O., Samovski, D. & Abumrad, N. A. Structure-function of CD36 and importance of fatty acid signal transduction in fat metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 34, 281–303 (2014)

Ellis, J. M. et al. Adipose acyl-CoA synthetase-1 directs fatty acids toward beta-oxidation and is required for cold thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 12, 53–64 (2010)

Kermorvant-Duchemin, E. et al. Trans-arachidonic acids generated during nitrative stress induce a thrombospondin-1-dependent microvascular degeneration. Nat. Med. 11, 1339–1345 (2005)

Glatz, J. F., Luiken, J. J. & Bonen, A. Membrane fatty acid transporters as regulators of lipid metabolism: implications for metabolic disease. Physiol. Rev. 90, 367–417 (2010)

Holmes, R. S. Comparative studies of vertebrate platelet glycoprotein 4 (CD36). Biomolecules 2, 389–414 (2012)

Kennedy, D. J. & Kashyap, S. R. Pathogenic role of scavenger receptor CD36 in the metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 9, 239–245 (2011)

Shi, Y. & Burn, P. Lipid metabolic enzymes: emerging drug targets for the treatment of obesity. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 695–710 (2004)

Mwaikambo, B. R., Sennlaub, F., Ong, H., Chemtob, S. & Hardy, P. Activation of CD36 inhibits and induces regression of inflammatory corneal neovascularization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 4356–4364 (2006)

Klenotic, P. A. et al. Molecular basis of antiangiogenic thrombospondin-1 type 1 repeat domain interactions with CD36. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 1655–1662 (2013)

Nath, A. & Chan, C. Genetic alterations in fatty acid transport and metabolism genes are associated with metastatic progression and poor prognosis of human cancers. Sci. Rep. 6, 18669 (2016)

Weber, J. M. Metabolic fuels: regulating fluxes to select mix. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 286–294 (2011)

Ye, X. et al. Distinct EMT programs control normal mammary stem cells and tumour-initiating cells. Nature 525, 256–260 (2015)

Del Pozo Martin, Y. et al. Mesenchymal cancer cell-stroma crosstalk promotes niche activation, epithelial reversion, and metastatic colonization. Cell Reports 13, 2456–2469 (2015)

Pein, M. & Oskarsson, T. Microenvironment in metastasis: roadblocks and supportive niches. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 309, C627–C638 (2015)

Fischer, K. R. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature 527, 472–476 (2015)

Zheng, X. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature 527, 525–530 (2015)

Celià-Terrassa, T. et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition can suppress major attributes of human epithelial tumor-initiating cells. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1849–1868 (2012)

Pavlovic, M. et al. Enhanced MAF oncogene expression and breast cancer bone metastasis. J. Natl Cancer Inst . 107, djv256 (2015)

Hale, J. S. et al. Cancer stem cell-specific scavenger receptor CD36 drives glioblastoma progression. Stem Cells 32, 1746–1758 (2014)

Nath, A., Li, I., Roberts, L. R. & Chan, C. Elevated free fatty acid uptake via CD36 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 5, 14752 (2015)

Oshimori, N., Oristian, D. & Fuchs, E. TGF-β promotes heterogeneity and drug resistance in squamous cell carcinoma. Cell 160, 963–976 (2015)

Myers, J. N., Holsinger, F. C., Jasser, S. A., Bekele, B. N. & Fidler, I. J. An orthotopic nude mouse model of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 293–298 (2002)

Benaich, N. et al. Rewiring of an epithelial differentiation factor, miR-203, to inhibit human squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. Cell Reports 9, 104–117 (2014)

Myers, J. N., Holsinger, F. C., Jasser, S. A., Bekele, B. N. & Fidler, I. J. An orthotopic nude mouse model of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 293–298 (2002)

Pece, S. et al. Biological and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers correlates with their cancer stem cell content. Cell 140, 62–73 (2010)

Roesch, A. et al. A temporarily distinct subpopulation of slow-cycling melanoma cells is required for continuous tumor growth. Cell 141, 583–594 (2010)

Bragado, P. et al. Analysis of marker-defined HNSCC subpopulations reveals a dynamic regulation of tumor initiating properties. PLoS One 7, e29974 (2012)

Qin, J. et al. The PSA(-/lo) prostate cancer cell population harbors self-renewing long-term tumor-propagating cells that resist castration. Cell Stem Cell 10, 556–569 (2012)

Zuber, J. et al. Mouse models of human AML accurately predict chemotherapy response. Genes Dev. 23, 877–889 (2009)

Yu, Z. et al. Sensitivity of squamous cell carcinoma lymph node metastases to herpes oncolytic therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1897–1904 (2008)

Wolins, N. E. et al. OP9 mouse stromal cells rapidly differentiate into adipocytes: characterization of a useful new model of adipogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 47, 450–460 (2006)

Hu, Y. & Smyth, G. K. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J. Immunol. Methods 347, 70–78 (2009)

Nowak, J. A. & Fuchs, E. Isolation and culture of epithelial stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol . 482, 215–232 (2009)

Spangenburg, E. E., Pratt, S. J., Wohlers, L. M. & Lovering, R. M. Use of BODIPY (493/503) to visualize intramuscular lipid droplets in skeletal muscle. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 598358 (2011)

Gonzalez-Roca, E. et al. Accurate expression profiling of very small cell populations. PLoS One 5, e14418 (2010)

Irizarry, R. A. et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 (2003)

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2008)

Gentleman, R. C. et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80 (2004)

Smyth, G. in Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor 397–420 (Springer, 2005)

Benjamini, Y. H. Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 57, 289–300 (1995)

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005)

Berriz, G. F., King, O. D., Bryant, B., Sander, C. & Roth, F. P. Characterizing gene sets with FuncAssociate. Bioinformatics 19, 2502–2504 (2003)

Barrett, T. & Edgar, R. Gene expression omnibus: microarray data storage, submission, retrieval, and analysis. Methods Enzymol . 411, 352–369 (2006)

Gao, J. et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal . 6, pl1 (2013)

Cerami, E. et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov . 2, 401–404 (2012)

Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70 (2012)

Acknowledgements

Research in the laboratory of S.A.B. for this project is supported by the European Research Council (ERC), the Government of Cataluña (SGR grant), the Fundación Botín and Banco Santander, through Santander Universities, and Worldwide Cancer Research. We would like to thank the Beug Stiftung Foundation for their support. S.M. was supported by a La Caixa International PhD fellowship. A.A. was supported by an EU Cofound postdoctoral fellowship. L.D.C. was supported by the Spanish ‘Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia’ (SAF2013-48926-P) and the European Commission’s 7th Framework Program 4DCellFate grant number 277899. We thank the Vall D´Hebron Research Institute Tumor Biobank for their assistance with the human samples. We also thank R. Wong for the Ln-7 cell line and J. Zuber for the PMSCV-Luc2-PGKneo-Ires GFP vector. IRB Barcelona is the recipient of a Severo Ochoa Award of Excellence from MINECO (Government of Spain). We thank V. Raker for manuscript editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P. and S.A.B. designed all experiments. G.P. performed all experiments with the help of M.M. for the histological characterization of the lipotoxicity and A.C. for the analysis of the gene expression data. A.A. established the patient-derived cells and the oral cancer orthotopic method. C.S.-O.A. and A.B. performed statistical analyses. J.A.H., C.B. and A.T. provided the tumours from patients. S.M. established the dye protocol to detect LRCs. N.P. performed the histopathology analysis of the mice. L.D.C. analysed expression data. G.P. and S.A.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The Institute for Research in Biomedicine in Barcelona has filed a provisional patent application that covers the application of inhibition of the fatty acid receptor CD3 by any method as an antimetastatic therapy against oral squamous cell carcinoma (European patent application number EP 2016/073208). Authors S.A.B., G.P., A.C. and M.M. are listed as inventors.

Additional information

Reviewer Information Nature thanks A. Harris and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Orthotopically inoculated human oral squamous cell carcinomas contain a slow-cycling sub-population of CD44bright cells.

a, Overview of the tumorigenic and metastatic activities of the different OSCC cell lines injected into the tongues of NSG mice. b, Tumour development from mice injected with OSCC-pLuc-GFP cells (using the cell lines indicated). Tumour growth was monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) over a four-week period. Data are given as the mean ± s.e.m. c, Frequency of metastases in the lymph nodes. a–c, Detroit-562 cells, two independent experiments: exp. 1 n = 10 mice; exp. 2 n = 11 mice; VDH-02, n = 20 mice; VDH-01, n = 20 mice; VDH-00, n = 8 mice; SCC-25, three independent experiments: exp. 1 n = 13 mice, exp. 2 n = 17 mice, exp. 3 n = 7 mice; JHU-029, three independent experiments, n = 12 mice per experiment; FaDu, two independent experiments, exp. 1 n = 14 mice, exp. 2 n = 5 mice. d, Immunofluorescence analysis of in vitro cultured OSCC-RFP cells pulsed with DID and grown in 2D culture for 16 days. e, f, Flow cytometry analysis of dye-pulsed OSCC cells in vitro showing the kinetics of dye dilution. Data are given as mean fluorescence intensity. g, FACS strategy to FACS-sort CD44bright dye+, CD44bright dye− and CD44dim cells from OSCC-pLucGFP oral tumours. Viable single cells were selected if GFP+ but negative for a lineage (Lin) cocktail of antibodies (H2KD, CD31 and CD45), to select human cells. GFP+ Lin− cells were gated for CD44 and dye. Percentages from the total GFP+ Lin− SCC-25 parental tumour are shown. h, Representative flow cytometry analyses to detect quiescent slow-cycling CSCs from OSCC cell lines. g, h, n = 8 animals per OSCC cell line. i, Global quantification of CD44bright dye+, CD44bright dye− and CD44dim cells from OSCC-pLucGFP tumours reported in g and h. j, Immunofluorescence analysis of SCC-25-pLucGFP and JHU-029-pLucGFP primary tumours, collected five weeks after OSCC inoculation, to detect dye+ quiescent slow-cycling cancer stem cells (CSCs). Insets show a magnification of dye+ cells that co-localized with the CD44 marker. SCC-25, n = 5 tumours; JHU-029, n = 5 tumours. k, Percentage of dividing cells by flow cytometry analysis in the dye+, dye− and CD44dim populations. Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 2 Oral SCC label-retaining cells are defined by a lipid metabolism and metastasis transcriptome signature.

a, Microarray analysis and heatmap of mRNA expression showing differentially expressed genes in dye+, dye− and CD44dim cells. n = 4 biological replicates and 8 mice per replicate. b, Gene ontology (GO) analysis showing the top categories for diseases, biological processes and signal transduction pathways that were upregulated in the proliferative active (DID−) as compared to LR-CSCs (DID+) populations. The resulting GO terms highlighted cell cycle–related categories. c, Over-represented genes in Dye+ and Dye− populations. d, Lipid metabolism genes over-represented in dye+ cells. e, Gene ontology (GO) analysis showing top diseases and biological processes categories upregulated in the DID+ (LR-CSCs) and DID− (proliferative) sorted populations from dye-pulsed Detroit-562 tumours analysed by microarrays. f, RT–qPCR validation by human-specific TaqMan gene expression assays of differentially expressed genes by microarray in the CD44+ DID+ and CD44+ DID− populations. Data are given as relative expression levels. Human β-2-microglobulin was used as internal control gene. n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, two-tailed t-test. g, Gene expression overlapping analysis of the LR-CSC signatures from SCC-25 and Detroit-562 tumours showing the top represented common diseases and biological processes. Metastatic processes and lipid metabolism-related categories are highlighted in red. P = 2.10 × 10−49, hypergeometric test. h, Correlation between CD36 expression and DiD content for orthotopic transplants of SCC-25, JHU-029, Detroit-562, FaDu, VDH-00, VDH-01 and VDH-02 cells (n = 8 animals per cell line). Numbers indicate percentages from the total GFP+Lin− OSCC parental tumour. Results are given as the mean ± s.e.m. (n = 7 OSCC orthotopic transplants; ***P = 0.0008, *P= 0.03, two-tailed t-test).

Extended Data Figure 3 LRCs correspond to CD36+ cells, and CD36 overexpression promotes metastatic initiation and progression.

a, CD36+ CD44bright OSCC cells detected by flow cytometry analysis of tumours from orthotopic transplants. Tumours were obtained from OSCC Detroit-562 (three independent experiments: exp. 1 n = 3, exp. 2 n = 3, exp. 3 n = 4 mice), JHU-029 (three independent experiments: exp. 1 n = 3, exp. 2 n = 3, exp. 3 n = 4 mice), SCC-25 (n = 8 mice), FaDu (n = 8 mice), VDH-00 (n = 8 mice), VDH-01 (n = 8 mice) and VDH-02 cells (n = 8 mice). Numbers indicate CD44bright CD36bright or CD44bright CD36low cells in the represented gate, expressed as percentages from the total GFP+ Lin− OSCC parental tumour. Histograms show the correlation between CD36 expression and the DID content. The average counted events as a function of dye fluorescence intensity is reported for each population CD44bright CD36bright and CD44bright CD36low. b, BLI monitoring of tumours generated by SCC-25 cells (empty vector (EV) n = 7 and Cd36 overexpression (OE) n = 17 mice), or JHU-029 cells (EV n = 19 and Cd36 OE n = 24 mice), transduced with PMSCV-EV (empty vector) or Cd36-overexpression vector. Graphs show the frequency of developed tumours (SCC-25 ***P = 0.05, JHU-029 ***P = 0.03, Fisher exact test) and BLI signal quantifications (primary tumour, *P = 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001; metastasis, **P = 0.007, *P = 0.01, two-tailed t-test). Data are given as the mean ± s.e.m. c, d, Haematoxylin and eosin staining (c) and anti-human CD44 immunostaining (d) of lymph nodes isolated from animals reported in a (n = 5 animals per group). e, RT–qPCR analysis of OSCC parental and CD36OE cells. Human β-2-microglobulin was used as internal control gene (n = 3 biological replicates, **P < 0.005, *P < 0.05, two-tailed t-test), data are given as the mean ± s.e.m. f, g, Flow cytometry analysis of OSCC tumours derived from PMSCV-EV or CD36OE cell transplants (n = 5 animals per group). Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 4 Depletion of CD36 inhibits metastatic initiation and progression.

a, BLI signal quantifications (*P = 0.01, two-tailed t-test) and frequency of developed tumours (*P = 0.04, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) of PMSCV-EV and CD36–overexpressing tumours from VDH-00 primary cell line (PMSCV-EV, n = 7; CD36OE, n = 8). b, BLI monitoring of tumours from FaDu cell line transduced with either PLKO or shRNA CD36 (two independent experiments: exp1. and exp.2, n = 5 mice per group). Graphs show the frequency of developed tumours, and BLI signal quantification (metastasis lymph node, *P = 0.05; metastasis lung, **P = 0.002; two-tailed t-test). c, d, Flow cytometry analysis of tumours from OSCC cells transduced with PLKO or shRNA CD36#99. Numbers indicate the percentages of CD44bright CD36+, CD44bright CD36– or CD44dim cells in the represented gate (n = 6 animals per group). e, Relative RNA levels of CD36 in SCC-25 parental and shRNA CD36 cells, determined by RT–qPCR analysis using TaqMan gene expression assay. Human β-2-microglobulin was used as internal control gene (n = 3 biological replicates, ****P < 0.005, two-tailed t-test). Data in a, b, e, are given as the mean ± s.e.m. f, Representative images of lungs from mice transplanted with PLKO or shRNACD36 FaDu cells (PLKO, n = 5 mice; shRNA CD36#99, n = 5 mice). g, Haematoxylin and eosin staining of metastatic lymph nodes from cells transduced with PLKO or shRNA Cd36. h, Representative haematoxylin-eosin staining of primary tumours from transplanted SCC-25 cells transduced with PLKO or Cd36 shRNA (n = 5 mice per group). Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 5 CD36+ cells are defined by a lipid metabolism and metastatic signature, and require the fatty acid β-oxidation enzyme ACSL1 to promote metastasis.

a, b, Top categories for diseases (a) and biological process (b) upregulated in CD36+ CD44bright cells. c, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) plot of CD36-associated signatures, highlighting strong enrichment for fatty acid metabolism. NES denotes normalized enrichment score. d, Comparative analysis of overlapping genes between CD36+ CD44bright and CD44bright DID+ upregulated signature, highlighting over-represented genes associated with lipid metabolism, cancer invasion and metastasis and transport and metabolism of nucleoside drugs. P = 1.359 × 10−16, hypergeometric test. e, Flow cytometry analysis of in vitro SCC-25 cells co-cultured with adipogenic OP-9 cells, showing the expression of three enzymes of fatty acid β-oxidation (ACADVL, ACADM and HADHA). Histograms show the average normalized number of events as a function of fluorescence intensity for the three enzymes (n = 2 biological replicates). f, BLI monitoring of tumours generated from OSCC cells transduced with either scrambled shRNA (SCR, n = 5 mice) or shRNA ACSL1#936 (n = 5 mice). Graphs show the frequency of developed tumours and the BLI signal quantification (**P = 0.001 and *P = 0.003, two-tailed t-test). g, Haematoxylin and eosin staining of metastatic lymph nodes from animals reported in f, showing the smaller metastases arising from Acsl1 shRNA transplants as compared to the control SCR (n = 5 animals per group). h, BLI monitoring of orthotopic transplants from CD36-overexpressing JHU-029 cells transduced with either control (SCR, n = 10 mice) or shRNA ACSL1#936 (n = 10 mice). Graphs show the BLI signal quantification (metastasis: *P = 0.03 and *P = 0.03, two-tailed t-test) and the frequency of developed tumours (CT vs OE-SCR *P = 0.03 and OE-SCR vs OE-shACSL1 *P = 0.04, Fisher exact test). i, Histogram shows the average normalized number of events as a function of CD36 fluorescence intensity. j, Relative RNA levels of OSCC cells reported in j, by RT–qPCR analysis. Human β-2-microglobulin was used as internal control gene (n = 3 biological replicates, P = 0.03, two-tailed t-test). Data in f, h, j, are given as the mean ± s.e.m. Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 6 CD36+ cells are stimulated by a high-fat diet or adipocyte-conditioned medium, and require the ability of CD36 to internalize fatty acids for their pro-metastatic potential.

a, Flow cytometry analysis of orthotopic transplants of Detroit-562 cells transduced with PLKO or shRNACD36#98 or #99, from mice fed with high-fat diet (HFD) or control diet (CD), analysed 4 weeks after OSCC injection. Numbers indicate CD44bright CD36+, CD44bright CD36– and CD44dim (differentiated) cells in the represented gate, expressed as percentages from the total GFP+ Lin– OSCC parental tumour. n = 5 animals per group. b, Flow cytometry analysis of co-cultured SCC-25/OP-9, SCC-25/adipogenic OP9 or SCC-25/HNCAFS (head and neck cancer–associated fibroblasts) cells. Numbers indicate CD36+ cells in the represented gate, expressed as percentage. c, FACS analysis of co-cultured Detroit-562 or SCC-25 with OP9 (control) or adipogenic OP9, showing an increase in the percentage of CD36-positive cells in the adipogenic co-cultures. Numbers indicate CD44bright CD36+ and CD44bright CD36– from the total GFP+CD29− OSCC cells. d, CD36 mRNA relative expression levels, measured by RT–qPCR, from SCC-25 CD36– sorted cells either co-cultured with adipogenic OP9 (Ad.OP9) cells or not, or from SCC-25 CD36+ sorted cells co-cultured with Ad.OP9 cells. In b–d, OSCC were co-cultured in vitro for 2 days. e, Flow cytometry analysis of OSCC cells co-cultured with adipogenic OP-9 cells or with 0.4 mM palmitic acid (PA). Histograms show the average normalized number of events as a function of CD36 and CD44 fluorescence intensity. f, cDNA and amino acid sequence of the CD36 receptor at the level of the point mutation introduced to generate the fatty acid-binding site mutant, CD36-K164A (left). Fatty acid uptake assay is shown for SCC-25 cells not transduced (as control, CT) or transduced with CD36wt (overexpressing wild-type CD36), shRNA Cd36 or CD36-K164A. g, BLI monitoring of transplants from SCC-25 cells overexpressing CD36wt (wild-type, n = 10) or CD36-K164A (n = 10). Frequency of developed tumours is expressed as percentage (*P = 0.02, Fisher exact test), and BLI signal quantification is expressed as the relative normalized photon flux (* P= 0.05, two-tailed t-test). Data are given as the mean ± s.e.m. h, FACS analysis of OSCC cells overexpressing either CD36 wild-type (wt) or mutant (Lys164mut). Histograms show the average normalized number of events as a function of CD36 and CD44 fluorescence intensity. Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 7 Inhibition of CD36 results in metastatic lipotoxicity, and CD36+ cells are the only cells capable of initiating metastasis.

a, Representative haematoxylin and eosin staining of metastatic lymph nodes from SCC-25-pLucGFP transplants with overexpressed wild-type CD36 or CD36-K164A. Dashed line denotes the areas surrounded by lipid droplets in the CD36-K164A-expressing cells. b, c, Caspase-3 immunostaining of the metastases reported in a and in Cd36 shRNA FaDu-pLucGFP metastatic lymph nodes, showing activated casp-3-positive apoptotic cells in the vicinity of droplets. d, Relative expression levels expressed as percentages of four populations, CD36+ CD44bright, CD36+ CD44dim, CD36− CD44bright and CD36− CD44dim, as determined by FACS analysis of the primary tumour and metastasis of the OSCC cell lines SCC-25, JHU-029, Detroit-562 and FaDu and the PDCs VDH-00, VDH-01 and VDH-02 (n = 4 biological replicates per cell line). e, Genes differentially expressed between CD36+ CD44bright and CD36+ CD44bright populations validated by RT–qPCR with human-specific TaqMan gene expression assays in SCC-25 EV (empty vector), SCC-25 CD36-overexpressing and SCC-25 Cd36 shRNA cells grown in vitro. Human β-2-microglobulin was used as internal control gene (n = 4 biological replicates, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005, two-tailed t-test). f, OSSC cells were co-cultured with adipogenic OP9 cells, FACS-sorted and injected into the oral cavity of NSG mice. g, FACS strategy to isolate CD36+ CD44bright, CD36− CD44bright and CD44bright cells from in vitro SCC-25 cells co-cultured with adipogenic OP-9 cells. Serial limiting dilutions of the different populations were injected immediately after FACS sorting. h, i, BLI monitoring (h) and primary tumour quantification (i) of mice injected with CD44bright CD36+ or CD44bright CD36– cells. Yellow arrows denote increased affinity in injected OSCC for the metastatic place, observed in some animals. j, k, Metastasis-initiating cell (MIC) frequency (j) and tumour-initiating cell (TIC) frequency (k) of the three different populations in g, as determined by ELDA software statistical analysis. Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 8 CD36+ cells recapitulate the cellular and molecular heterogeneity of primary tumours and metastases when orthotopically transplanted.

a, Overview of experimental set-up. Detroit-562 cells co-cultured with adipogenic OP-9 cells were FACS-sorted to select the CD44bright and CD36+ CD44bright populations. Selected cells were then injected orthotopically into NSG mice. Tumours were collected after 4 weeks, and cells were isolated for gene expression analysis by microarray. b, CD36-associated signatures from lymph node metastases arising from CD36+ CD44bright or primary tumour CD44bright transplants, showing the top upregulated categories for diseases and biological processes. c, GSEA analysis of lymph node metastases from CD36+ CD44bright and primary tumours from CD44bright transplants. Ranked lists of primary tumour comparison versus top 300 genes of lymph node-Met sorted by fold change (FC) and ranked lists of lymph node-Met CD36+ comparison versus top 300 genes of primary tumour sorted by fold change (FC). Nominal P < 0.0001. All source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Figure 9 Anti-CD36 neutralizing antibodies inhibit metastatic initiation, and cause metastatic regression of oral SCC.

a, BLI quantification of tumours from mice treated with anti-CD36 FA6.152 (anti-CD36 FA6.152, n = 3 mice; IgG1, n = 3 mice; **P = 0.004, two-tailed t-test). b, d, BLI monitoring of tumours from mice treated daily with anti-CD36 JC63.1 (anti-CD36: n = 5 mice; anti-IgA isotype control, n = 5 mice). Graphs show the BLI signal quantification (*P = 0.04, two-tailed t-test). c, Representative pictures of metastatic lymph nodes of animals treated daily with JC63.1 or IgA for 2.5 weeks. e, Activated caspase-3 immunostaining of metastatic lymph nodes of Detroit-562 transplants from mice treated with monoclonal anti-CD36 JC63.1 (10 μg per 100 μl), or with the IgA isotype control. f, BLI monitoring of immunocompetent C3H/HeJ mice treated daily with monoclonal JC63.1 or IgA. Graphs show BLI signals from tumours (*P = 0.05, two-tailed t-test). g, Fold change in metastasis BLI signal of the animals reported in d. h, Representative haematoxylin and eosin staining of liver, spleen, thymus and kidney of mice from f. No pathological differences related to anti-CD36 treatment were found (n = 10 animals per group). Data in a, d, f, g are given as the mean ± s.e.m.

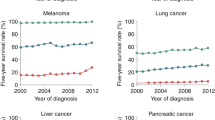

Extended Data Figure 10 Expression of CD36 correlates with poor prognosis in several human tumours, and inhibition of CD36 inhibits metastasis of human melanoma and luminal A breast carcinoma cell lines.

a, Correlation of CD36-associated signature expression or CD36 expression with overall and disease-free survival for patients. Red and green lines denote patients whose tumours expressed signatures or CD36 higher and lower than the median, respectively. b, BLI signals from metastasis developed in NSG mice injected with MCF-7 (PLKO, n = 10; Cd36 shRNA, n = 10 mice) and 501mel (PLKO, n = 10; Cd36 shRNA, n = 10 mice) cells (for breast MCF-7, *P = 0.04, two-tailed t-test and for melanoma 501mel, ***P = 0.0001 in liver metastasis and **P = 0.0003 in lung metastasis, two-tailed t-test). c, Relative proportion of developed metastases from mice in a (*P = 0.05, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). d, BLI signals from primary tumours and relative blood and lung GFP RNA levels measured by qPCR analysis after intravenous injection of Detroit-562 and SCC-25 cells transduced with empty vector (control) or shRNA Cd36. Samples were collected immediately after injection (T-0h) and 12 and 48 h (T-12h and T-48h, respectively) after injection (n = 3 animals per time point in each of the groups; *P ≤ 0.05, two-tailed t-test). Data in b, d, are given as the mean ± s.e.m. e, GSEA of EMT genes in CD36+ and CD36− cells sorted from primary oral lesions (generated from CD44bright inoculated cells), or from lymph node metastases (generated from CD36+ CD44bright inoculated cells). CD36− cells express higher levels of EMT genes than CD36+ cells in both the primary lesion and lymph node metastases. Genes are ranked by t-statistic value. Enriched populations are indicated for each of the plots. Lower panels show the GSEA analysis of the same cohort of EMT genes compared between lymph node metastases and primary oral lesions within CD36+ cells or CD36− cells. Source data from mouse experiments are in Supplementary Information.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains full legends for Supplementary Tables 1-8 and Supplementary Tables 9-11. (PDF 165 kb)

Supplementary Tables

This zipped file contains Supplementary Tables 1-8. (ZIP 21896 kb)

Source data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pascual, G., Avgustinova, A., Mejetta, S. et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature 541, 41–45 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20791

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20791

This article is cited by

-

Unraveling the complexity of STAT3 in cancer: molecular understanding and drug discovery

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2024)

-

Dietary factors and their influence on immunotherapy strategies in oncology: a comprehensive review

Cell Death & Disease (2024)

-

Lipids as mediators of cancer progression and metastasis

Nature Cancer (2024)

-

VAV2 orchestrates the interplay between regenerative proliferation and ribogenesis in both keratinocytes and oral squamous cell carcinoma

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Effects of dietary intervention on human diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.