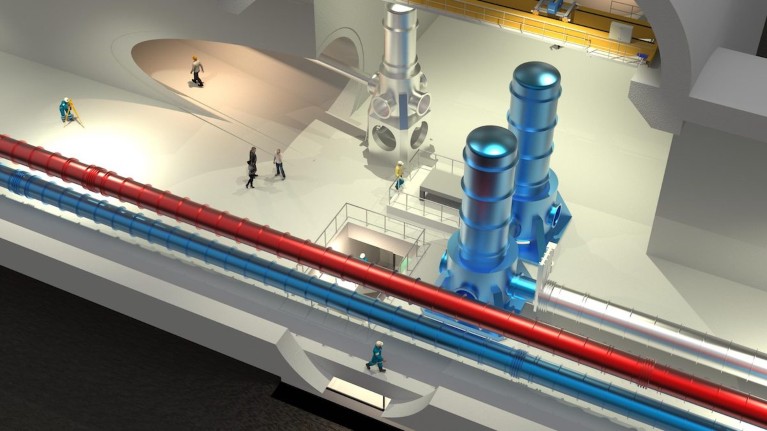

Artist's impression of the interiors of the Einstein Telescope. Credit: Marco Kraan/Nikhef.

The competition between Italy and the Netherlands to host the next generation gravitational wave detector might end in a draw if a new proposal to build two detectors instead of one gains momentum.

Due to become operational by 2035, the Einstein Telescope was originally proposed as a triangle with 10-kilometer sides located nearly 300 metres underground to reduce noise sources. Around each vertex there would be a pair of V-shaped interferometers, optimized to detect low and high frequency gravitational waves, respectively. It is expected to be 10 times more sensitive than the current gravitational detectors, LIGO in the United States, Virgo, in Italy and KAGRA in Japan. Italy and the Netherlands are currently preparing their bids to host the telescope. The Italian site is in Sardinia, at the Sos Enattos dismissed mine near the village of Lula, while the Netherlands one is at the border with Belgium and Germany, near the city of Maastricht.

But now the international collaboration that manages the project has started to consider an alternative design, based on two L-shaped interferometers with 15-kilometre arms, one at Sos Enattos and the other at Maastricht, about 1,000 kilometres apart.

“The two designs will be considered and compared by the ET preparatory phase project, which is working to deliver the technical design report of the telescope,” says Eugenio Coccia, director of the Institut de Física d'Altes Energies in Barcelona, and chair of the ET collaboration board. He says that having two L-shaped detectors would reduce the operational risk. “If one has problems and requires intervention, the other would still be able to run.” But, the comparison will also consider scientific quality, feasibility and costs, and Coccia notes that two detectors could pose political and management challenges. "Several member states and their funding agencies would need to agree and fund two machines in different countries,” he notes.

As for science, a recent study1 led by Marica Branchesi, astronomer at the Gran Sasso Science Institute and co-chair of the ET observational science board, concluded that two L-shaped detectors would lead to better results. “For nearly all the science cases we have considered, two L-shaped detectors would be able to observe from two to three times the number of events that the triangle would see,” Branchesi explains. She adds that this design would also allow to better locate the source of each gravitational wave in the sky, which is critical for pointing optical telescopes in the right direction and observing the light emitted by merging neutron stars.

Chris van den Broeck, a physicist at Utrecht University and a co-author of the study that compared the two designs, says that the triangle design may still have an advantage when it comes to analysing noise. Current detectors see nearly one signal per week, which means they observe long stretches of data containing only noise. While this is a limitation, it allows characterization of the noise and is better to distinguish a gravitational wave when it comes by. Because of ET’s sensitivity, there will not be any stretch of data without a signal, and therefore noise will be harder to study. But unlike the L-shaped design, the triangle geometry provides a way around the problem. “By summing up the measurements of the three pairs of detectors in the triangle, you obtain only noise and you can study it,” van den Broeck explains.

Finally, there are costs and feasibility. Building ET would cost around € 2 billion, about half of which for the tunnels, and would be funded by the site’s country government, while the other half would be for the interferometers themselves.“Infrastructure costs would roughly be equal in the two configurations,” says Fernando Ferroni, a physicist at the Gran Sasso Science Institute and co-director of the ET organization, the body that will negotiate with the government delegates of the collaboration member states. Ferroni, who is also on the committee that supports the Italian candidacy, says that he is quite confident the Italian government and the Sardinia region, that have committed around €1 billion, would not withdraw their support if Italy ended up hosting only one of the two detectors.

Andreas Freise, an experimental physicist at Vrije Universiteit of Amsterdam, and co-director of the ET organisation with Ferroni, says he cannot anticipate whether the Dutch government would still be funding the construction if ET ended up having two sites, as he is not part of the team that is preparing the bid.

“At the moment we have just started the characterization of the two sites,” he says. “The cost of building the infrastructure depends on the quality of the site both underground, because some rock types are easier to excavate, and above-ground, where you may need to build roads and maybe even a harbour to deliver machinery.” For these reasons, Freise believes that the decision will be based more on feasibility and costs than the science.