As countries in Europe and elsewhere roll back strict measures against COVID-19 and aim to soon declare the pandemic over, African countries and their public health stakeholders are also starting to shift their attention. Vaccination continues to remain important, but the focus is moving on to longer-term testing and surveillance approaches that can be integrated into, and will strengthen, national health systems.

Available tools

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), noted in January 2022 that the world will be living with COVID-19 for the foreseeable future.

“We will need to learn to manage [COVID-19] through a sustained and integrated system for acute respiratory diseases, which will provide a platform for preparedness for future pandemics,” said Tedros, in his speech to the WHO executive board.

But not all parts of the world are moving at the same pace. “Depending on where you live, it might feel like the COVID-19 pandemic is almost over — or it might feel like it’s at its worst,” Tedros said a month later in February 2022.

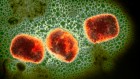

Tedros noted that the tools to prevent this disease, to test for it and to treat it are now available and are helping countries to bring the virus under control. But where these tools are not being used, SARS-CoV-2 continues to spread, evolve and kill.

In Africa, less than 13% of the population had been fully vaccinated as of March 2022. In a continent of 1.4 billion people, only about 693 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been received, with nearly 40% of these doses not yet administered.

Among African countries, vaccination coverage ranges from 85% of the Seychelles’ population being fully vaccinated to only 0.8% in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In Nigeria, only 8.4% of people have received a first dose, in a country that has administered the continent’s fifth highest number of doses (about 18 million).

Billions needed

On 9 February 2022, world leaders launched a call to end the COVID-19 pandemic by funding the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, a partnership that is providing low and middle-income countries with tests, treatments, vaccines, and personal protective equipment (PPE).

The ACT Accelerator currently has a funding gap of US$16 billion that it needs to create a pandemic vaccine pool of 600 million doses, support community engagement and cover logistical costs — in order to achieve the goal of 70% vaccine coverage in all countries by mid-2022.

Extra money is also needed for the procurement of 700 million tests, drugs to treat 120 million patients, 433 million cubic meters of oxygen and PPE for 1.7 million health workers, as well as research funding for clinical trials, variants of concern and broadly protective coronavirus vaccines.

ACT Accelerator hub lead Bruce Aylward tells Nature Medicine that in parallel with tackling the acute crisis, the hub is also working on the larger financing gap beyond 2022, as the world begins to come to terms with endemic COVID-19.

“Some of [the funding] will have a longer term investment impact, but we really need to tackle that at a whole different scale,” he said.

Aylward noted that new funding must prioritize the local needs of African countries, something that has already started at the vaccine access institution COVAX, which is now only providing the vaccine doses requested by countries.

“Similarly, if we look at diagnostics, therapeutics and PPE, what we've done was to leverage the mechanisms that the Global Fund has in place, which really allows for country-driven planning,” he says.

Former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown wants the world to invest in healthcare infrastructure. Brown, who is the WHO’s Ambassador for Global Health Financing, tells Nature Medicine that long-term funding for healthcare infrastructure is the focus of a G20 task force, but awaits approval by world leaders, who will be eyeing its $15 billion–a–year price tag.

“The infrastructure would cost about US$10 to 15 billion a year and will have to be built up over the next few years. That requires a further decision by leaders that they are prepared to finance it,” says Brown.

New funding may also be needed to strengthen the in-country capacity of African nations, allowing them to re-build their economies as they prepare to live with COVID-19, requiring new funding facilities from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and regional development banks.

But funders will have high expectations for countries, should they provide this additional round of funding. “They will be expected to do more,” says Brown.

Inadequate testing

While vaccine rates remain low, the virus continues to circulate in Africa. But the true state of the pandemic is masked by inadequate testing. Although the continent accounts for nearly 17% of the world’s population, it accounts for only 1.8% of global tests.

Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) continues to assert that any African country that needs testing kits can have them, but a 31 January open letter to the WHO noted that the average daily testing rate of high-income countries is, per capita, nearly ten times higher than that of middle-income countries and is close to 100 times higher than that of low-income countries.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that six in seven SARS-CoV-2 infections go undetected in Africa. This suggests that the cumulative number of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Africa is 59 million, seven times more than the 8 million cases reported.

Matshidiso Moeti, WHO Regional Director for Africa, adds that testing needs to increase for various purposes in Africa, and the WHO is supporting countries to have access to the supplies that are needed.

In Rwanda, which has fully vaccinated about 54% of its population, mass testing will continue to be used, in order to track the spread of the virus and guide the government’s health interventions.

Albert Tuyishime, Head of Diseases Prevention and Control at the Ministry of Health and Rwanda Biomedical Centre, tells Nature Medicine: “I think we now know what works for prevention and what people should be doing. And on top of that, we now have this new tool, which is the vaccine. We are keeping our surveillance on the same level as when we were at the peak of the previous waves.”

By keeping testing at the highest level and encouraging the population to get vaccinated, Tuyishime argues that Rwanda will be able to win the war against COVID-19 and sustain the response beyond the acute phase of the pandemic.

“This is going to help us in really keeping the number of new cases low. But we’ve known that this pandemic is a bit unpredictable. So, we have to keep on watching, keeping our surveillance to the highest level so that we can identify a peak of cases and then implement impactful interventions,” says Tuyishime.

A frontline health worker administering COVID-19 vaccines, which could be produced in Africa in the future. Credit: Paul Adepoju.

Pharmaceutical sovereignty

Macky Sall, President of the Republic of Senegal, and new Chairperson for the African Union (AU), has one clear goal for after the pandemic: Africa’s pharmaceutical and medical sovereignty.

In his speech at the AU, Sall noted that the production of medical and pharmaceutical products has already been initiated on the continent, as has the production of vaccines.

“Beyond the response to COVID, we need to maintain this dynamism by maintaining health issues on our agenda, in order to support the emergence of an African pharmaceutical industry that can meet our essential needs and face pandemics like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria,” Sall told AU member states.

To this end, the AU has worked with Africa CDC to launch the Partnership on Africa Vaccine Manufacturing in 2021, to encourage countries to work together to identify capacities, mobilize resources and accelerate vaccine production in Africa, including mRNA vaccines.

Blade Nzimande, South Africa’s Minister of Higher Education, Science and Technology, describes the importance of the WHO technology-transfer hub, which has successfully copied the Moderna vaccine.

“The WHO mRNA global hub is a critical building block to ensure that South Africa and the whole continent has the production capacity that is essential for equitable vaccine rollout,” says Nzimande. “The mRNA technology is not only for COVID-19, we hope it can be adapted to help us in the fight against HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, which is why we’re investing heavily, alongside international partners, in this initiative.”

But the initiative has several hurdles to overcome, including the pharmaceutical industry itself, which is reportedly taking steps to undermine it. And with only microliters of the Moderna vaccine produced, enough doses for rollout are not expected to become available until beyond 2022.

Investing in people

The endemic phase of COVID-19 should also be accompanied by an investment in healthcare workers. Before COVID-19, Ghanaian biomedical and facilities engineer David Acolatse had no experience working with medical oxygen facilities. But about two years later, he spends his days traveling from one African country to another, helping to set up, maintain, service, repair and improve the productivity and operations of pressure-swing adsorption oxygen-generating plants, which produce medical-grade oxygen.

Acolaste is part of a team organized by Build Health International to improve medical oxygen systems in sub-Saharan Africa. But with the continent now coming to terms with endemic COVID-19, Acolatse says that the infrastructure for medical oxygen will outlive the pandemic.

“Medical oxygen is in use in surgical theaters and in intensive care units, as well as the care of people who suffer from pneumonia and other respiratory disorders,” says Acolaste.

The pandemic has drawn attention to the need to strengthen the delivery of community-based health services. As the pandemic response now goes into a long-term phase, boosting community health services is receiving attention from organizations such as the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

In February 2021, the IFRC announced a new collaboration with Africa CDC, geared toward strengthening community resilience and community-level responses to public health emergencies. So far, this includes providing testing support to African countries, helping with community mobilization, advocacy and scaling up of contact tracing.

As Africa prepares for endemic COVID-19, the IFRC’s regional director for Africa, Mohammed Omer Mukhier-Abuzein, tells Nature Medicine it is expanding its involvement and will train five million community health workers over the next five years.

“We have a five-year plan for pandemic and epidemic preparedness, including COVID,” says Mukhier-Abuzein. “Part of that plan for us is to strengthen the community health workers especially [in] the higher risk areas and the most vulnerable communities.”

Routine care

Preparing for endemic COVID-19 means integrating testing and treatment into existing health infrastructure. Sandile Buthelezi, Director-General of South Africa’s National Department of Health, tells Nature Medicine that South Africa plans to integrate COVID-19 vaccination into its routine immunization program, as is Rwanda. South Africa also plans to routinize COVID-19 testing in a similar way to malaria and HIV testing, and further leverage its pioneering genomic sequencing network for pathogen surveillance.

“It may be that in the end, [SARS-CoV-2 vaccination] transitions into something that may be similar to vaccination for influenza, of which we have some experience,” says Moeti, who wants to integrate and link vaccine delivery within other ongoing services.

Buthelezi has similar plans for testing: “We need to continue our surveillance like we do for most of the diseases, like we do with flu. But more importantly, with the strong genomic sequencing network that we have in the country we will be able to monitor and see if there are any more variants coming in and how to adjust our response.”

Buthelezi adds that the COVID-19 pandemic has been eye-opening in clarifying the limitations of public health laws: “We've adjusted our laws [for] how we deal not only with COVID-19 in an endemic phase, but with any other public health threats in the future, using the lessons that we've learned.”