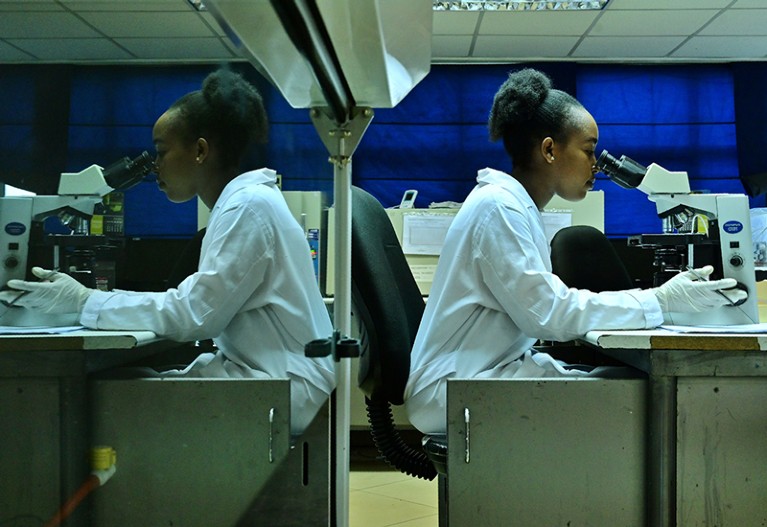

For his master’s degree in coaching, Simon Kay studied the career choices of Kenyan early-career researchers, such as these laboratory technicians in Nairobi.Credit: Tony Karumba/AFP/Getty

After gaining a PhD in immunology, Simon Kay spent 25 years managing bilateral programmes for the British Council, a cultural and educational charity, and as head of international partnerships for the London-based research funder Wellcome. He quit to become a full-time leadership and life coach in June 2021. The aim of coaching, he says, is to support behavioural change in others by increasing their self-knowledge and capacity for learning, through reflection. As a professional coach with a special interest in research environments, he wants to help both young and more experienced scientists to improve their self-awareness so as to foster a kinder and more nurturing research culture.

What prompted your career change?

To be honest, I was becoming a bit bored with organizational life. There are only so many risk-assessment meetings you can attend in a lifetime. And I’d become interested in psychology while at Wellcome. I’d worked there since 2012 as head of international partnerships, overseeing efforts to build research capacity in sub-Saharan Africa, India and southeast Asia. I started with a six-month course in 2019, and went on to gain a master’s degree in coaching and behavioural change at Henley Business School, part of the University of Reading, UK.

So how can coaching help researchers?

As a coach, you look at a person’s life as a whole, not just at their work life or personal life. I think that can be very valuable for researchers. In research, you have this incredibly critical approach to dissecting ideas and proposals, which I think comes at a huge emotional cost. A lot of academic leaders show very low levels of emotional self-awareness. If we want to improve research culture, then one way to do so is to develop the leadership skills of senior managers.

Is coaching just for people in leadership positions?

No. I see absolutely no reason why it shouldn’t be for younger people. In fact, for my master’s dissertation, I studied factors affecting the career identity and choices of Kenyan early-career researchers. But coaching early-career researchers is slightly different. When you’re coaching mid-career professionals, it’s likely that they’ll come with something that’s going wrong, or that they need a change of direction. Early-career people haven’t necessarily got a ready-made set of problems, and might need a more structured coaching approach.

How is coaching different from mentoring?

A mentor is more of an expert, offering expert advice based on their own experiences. As a coach, you don’t see yourself as an expert. Rather than advising, you help a client come to their own understanding through asking powerful questions. A coaching relationship starts by understanding a client’s goals. These will evolve over time. There are psychometric tools, which are a sort of window into a person and are helpful for starting the conversation. Then there are psychological techniques, which you use as you go along. For example, if someone has a thought that’s going round and round in their head, there’s a metaphor that you can apply, whereby the person places the thought on a leaf in a stream and watches it float away. It’s a way of helping them to cope with uncomfortable thoughts or feelings, and is part of something called acceptance and commitment therapy. A lot of the positive outcomes come from the trust that a person builds with their coach.

Simon Kay hopes to use his coaching skills to foster a kinder and more nurturing research culture.Credit: Ying Kay

How did your own understanding of coaching evolve?

During my PhD, at the University of Nottingham, UK, I spent two years coaching the university’s rowing team. The approach was the opposite of how I’ve since been trained to coach. Coaching then was shouting constant instructions on technique through a megaphone, never asking oarsmen to reflect on their performance. I like to think that later, in my working life, I helped others with their work and development. But on reflection, I’m sure there were doses of advice and telling them how to do their jobs. My recent coaching training definitely had an impact on my last year at Wellcome. I think I became a better listener. I also introduced the idea of fast and slow meetings. The latter are where you ensure that everyone has an opportunity to speak, including those who are more introverted and quiet.

Many researchers struggle with impostor syndrome. How would you coach somebody like that?

There are some positives with impostor syndrome. It’s not good to feel bad, but it also goes hand in hand with a sense of humility about what you can and can’t do. But excessive impostor syndrome can lead to overwork, lack of self-confidence and motivation, and burnout. Here, probably the starting point is actually helping that person connect with what’s important to them and their own value. What you’re trying to do is build up that person’s sense of self-worth.

What about someone who has been accused of bullying?

From a coaching perspective, that person actually needs help and compassion. Sometimes people think there’s only one way they can operate in the workplace. Coaching helps them to see that they can use a more flexible mix of behaviours that will allow them to keep their scientific edge while creating a more nurturing, caring environment. Paradoxically, assertiveness training can help people who become supercritical or aggressive under pressure. You might think it’s the last thing they need, but assertiveness training teaches people to state what they want clearly, in neutral terms, removing the criticism and emotion.

Why did you study the career choices of early-career researchers for your master’s dissertation?

I chose that topic because I am passionate about building research capacity, and it used to be what got me out of bed every day when I worked at Wellcome. I wanted to explore the personal factors that influence career identity. I interviewed 18 Kenyan early-career researchers, and 3 broad themes emerged. First, their identity was really forged by their passion to serve African society. Second, religious faith played a central part in their career decision-making, but it was a part of their cultural identity that they felt they had to suppress when they went to work in a foreign lab. And, finally, mentors were incredibly important for them, not just at higher levels of training, such as in PhD programmes and beyond, but even as undergraduates.

I developed a mentoring framework, in which three processes underpin both mentoring and training. The first is the cognitive bit of training someone to be a scientist. That’s the bit that I think most mentors are very comfortable with. The second is organizational, and is about teaching those being mentored to navigate and understand the whole business of research, how institutions work and what their place is in them. And the third bit is that mentors should see the whole person in front of them. It’s not trying to turn mentors into coaches, but I think some basic coaching training for them would be beneficial. If we can introduce researchers to leadership models who will help them to think about the kind of leader they want to be, it could break some of the negative patterns we see today in research.

The Olympic sport that influences my lab leadership style

The Olympic sport that influences my lab leadership style

How to blow the whistle on an academic bully

How to blow the whistle on an academic bully

How burnout and imposter syndrome blight scientific careers

How burnout and imposter syndrome blight scientific careers