Surgeons in Japan have transplanted kidney tissue from one rat fetus to another, while the recipient was still in its mother's womb. Study lead Takashi Yokoo, a nephrologist at Jikei University School of Medicine in Tokyo, says the surgery is the first step to one day transplanting fetal pig kidneys into human fetuses that develop without functioning kidneys.

“Our project is the first of its kind,” says Yokoo. Researchers have previously injected cells and amniotic fluid into fetuses1, including human ones, but these are the first reports of organ and tissue transplants in utero, he says.

Transplanting an organ before birth could allow it to grow and develop with the fetus, so that the organ is functioning at birth, and there is less risk of rejection.

“It’s lovely data,” says Glenn Gardener, a fetal surgeon at Mater Mothers’ Hospital in Brisbane, Australia.

Green kidneys

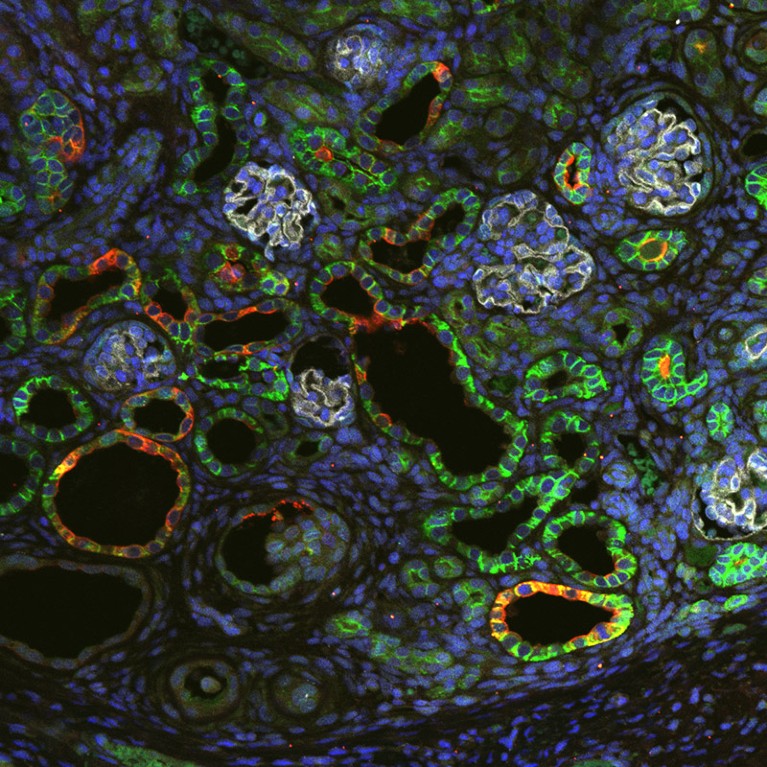

In their study, Yokoo and his colleagues genetically modified rats to express a green fluorescent protein in their kidneys, so that the tissue could be tracked. They then extracted the green kidney tissue from rat fetuses, and used a tiny needle to insert it under the skin of the backs of 18-day-old rat fetuses developing in their mothers’ wombs. The rat pups were born after the normal gestation period of around 22 days.

The tissue gradually developed, forming waste-filtering units known as glomeruli and well-divided inner and outer kidney structures. Two-and-a-half weeks later, the kidneys began to produce urine. “The timeline is considered to be almost identical to normal development,” says Yokoo. But because the transplanted kidney was not connected to the ureter, the urine had nowhere to go, so the researchers drained the kidney continuously until the rats were euthanized at around five months of age.

Of the nine fetuses that underwent surgical transplants in four pregnant rats, eight developed fluorescent-green kidneys. In the ninth fetus, the transplanted tissue probably did not embed successfully, says Yokoo.

A close look at the kidneys revealed that the fetuses’ blood vessels had grown inside the donated tissue, which made them less likely to be rejected by the immune system. A major cause of organ-transplant rejection is incompatibility between donor blood vessels and the host’s body, says Gardener. “In this case, the host is infiltrating the organ, and you overcome that. That was really cool.”

The rat study results2 were posted on the bioRxiv preprint server on 20 April and have not yet been peer reviewed.

Pig, monkey, human

Yokoo’s long-term goal is to transplant fetal pig kidneys into human fetuses with Potter syndrome, a condition in which the infant doesn’t develop functioning kidneys during gestation and usually dies hours after birth.

To test xenotransplantation — the use of animal organs in recipients of another species — Yokoo transplanted mouse kidney tissue into rat fetuses. The intervention was successful in four rats, and the kidneys developed for ten days without being rejected. By 18 days, the tissue showed signs of rejection, which could be quelled by immunosuppressant drugs. Yokoo says fetal tissue is less likely to induce an immune response than is adult tissue, which means that it does not need to be genetically modified before transplant to avoid rejection.

So far, researchers have attempted to genetically modify fully developed organs to bring xenotransplantation closer to the clinic. Last month, surgeons in the United States conducted the first transplant of a kidney from gene-edited pigs into a living adult. Surgeons in the United States and China have previously transplanted gene-modified pig hearts into living people, and gene-edited pig kidneys and a liver into people who lacked brain function.

This stained image shows the filtering part, or glomerulus, of the maturing kidney.Credit: K. Morimoto et al./bioRxiv

Yokoo says he has also conducted pig-to-pig fetal transplants in 38 pig fetuses in 11 sows, and 18 recipient piglets were born. These results have not been published. He is also conducting pig-to-monkey fetal transplants in marmosets, and hopes to start work on cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in a few months.

Yokoo’s rat experiments are a “small first step, but a very important one” on the path to xenotransplantation in people in Japan, says Maria Yasuoka, a medical anthropologist who studies organ transplantation at Otaru University of Commerce in Hokkaido, Japan.

Gardener says the results in rats are fascinating but still a long way from being applicable to humans. Other researchers agree: “In principle, the prospect of organ transplantation in utero is an amazing concept,” says Ahmet Baschat, a specialist in fetal interventions at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “Scientifically, it’s novel. It’s a beginning.” But, Baschat says he wouldn’t get too excited yet.

Yokoo has started engaging with members of the public to inform them of the benefits of human fetal xenotransplantation and gain their trust. He plans to apply for approval to conduct research in people from ethics boards at his university and hospital, and Japan’s regulatory agency.

First pig kidney transplant in a person: what it means for the future

First pig kidney transplant in a person: what it means for the future

First pig liver transplanted into a person lasts for 10 days

First pig liver transplanted into a person lasts for 10 days

Monkey survives for two years after gene-edited pig-kidney transplant

Monkey survives for two years after gene-edited pig-kidney transplant

Will pigs solve the organ crisis? The future of animal-to-human transplants

Will pigs solve the organ crisis? The future of animal-to-human transplants

First pig kidneys transplanted into people: what scientists think

First pig kidneys transplanted into people: what scientists think

First pig-to-human heart transplant: what can scientists learn?

First pig-to-human heart transplant: what can scientists learn?